Fast cars, full-on carnage, and fascist colonialism: revisiting the Tripoli Grand Prix

At the turn of the 20th century, the Ottoman rulers of Libya had long since lost control of their vast empire. Almost 400 years earlier in 1551, 6,000 Turks disembarked from ships at Tripoli along with 40 cannons, and captured the city with relative ease. With a coastline stretching thousands of kilometres and a desert leading into the unknown, this barely-touched vastness was a gateway not only to the Sahara, but to the whole of the African continent as well. In 1909, the American explorer Charles Wellington Furlong visited Tripoli, ‘a white-burnoosed city’ and ‘the most native of the Barbary capitals’, which he described as ‘[lying] in an oasis on the edge of the desert, dipping her feet in the swash and ripple of the sea’1. Many Orientalist accounts from this particular period praised the multiculturalism of Tripoli, a place where Phoenician monks, rabbis, imams, nuns, and priests could all be seen roaming the city’s streets2. Libya was by no means a Mediterranean utopia, but many still perceived it as a harmonious part of the world. It was no wonder, then, that the Italian colonialists later set their eyes on the coast.

The Italo-Turkish War begun on the 29th of September in 1911, sweeping across Libya’s vast coastline from Tripolitania to Cyrenaica. The Italians boasted superior military equipment and were the first army to use aerial warfare when they bombed a Turkish camp situated in the Ain Zara district. On the 18th of October in 1912, the Ottomans were officially defeated, and Italy’s seed was planted in Libya. Naturally, this instigated a rebellion in Cyrenaica fronted by the venerated Omar al-Mukhtar (celebrated in the 1981 Hollywood film Lion of the Desert), who bravely fought Libya’s colonial occupiers for almost 20 years until his capture and execution at the hands of the Italians in 1931.

Anthony Quinn as Omar al-Mukhtar (centre) on the set of Lion of the Desert

Italy concentrated its efforts in Tripolitania whilst struggling to overcome the rebellious areas of Cyrenaica and Fezzan. In the 1920s, the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini granted permission to the infamous General Rodolfo Graziani to front horrific attacks on Libyan citizens, in an attempt to quash any resistance. A recent and little-known novel, Ali Hussein’s Al-Agalia: The Camp of Suffering: A Boy’s Tale, tells the story of a concentration camp where thousands of prisoners where shackled to its arid land by hunger, humiliation, and deprivation, portraying a colonialism beyond tourism and architecture. As Hussein writes:

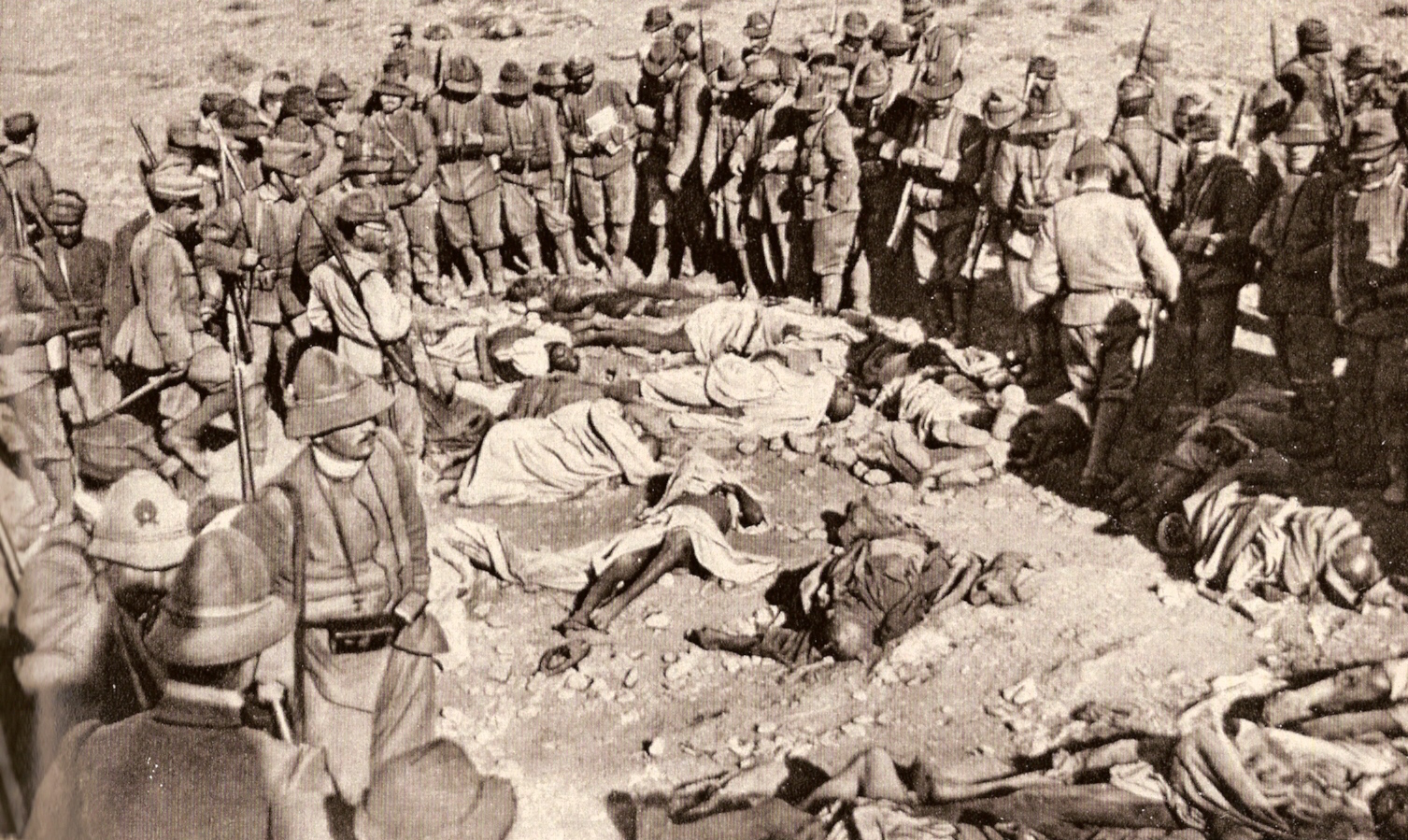

The Al-Agalia concentration camp is a shameful reminder of Graziani’s service to the Italian people in the Mussolini era. Sixty-five thousand people perished in these camps. They were set in wastelands, tents behind barbwire, guarded by armed Italians and ruthless African mercenaries3.

The corpses of Tripoli’s Libyan and Ottoman Turkish defenders surrounded by Italian troops in 1911

Far away from the devastation, however, Tripoli was being transformed into Italy’s gem of North Africa, with monumental projects being undertaken to modernise the newly-occupied land. The geographical significance of the city meant it was accessible for wealthy visitors who could swap familiar extravagances for things rather different. One need only imagine boarding a luxurious liner cruising over the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean, towards a land unknown. Vast golden landscapes appear on the horizon, followed by a white blimp marking Tripoli in the distance. Tourism, as Tripolitania Governor Giuseppe Volpi envisaged, would be a key factor in the colony’s economic growth, and perhaps more importantly, a key component of the aesthetics of colonial power. Libya provided the perfect backdrop for the Italian tourism industry. A balance between the indigenous culture and Italy’s efforts to modernise was behind preservation projects such as – first and foremost – the Arch of Marcus Aurelius. Roman heritage was a priority, along with the modernisation of Libya, which included the introduction of a new network of water and sanitary services. The Italians saw themselves as the rightful heirs to Libya who would bring pride to the Empire by restoring ‘civility’ in the land of a ‘barbaric’ and ‘regressive’ culture.

Tripoli’s Citta Vecchia (Old City) in an Italian postcard from the 1930s

Roads were being built to increase mobility between towns and cities that had only been accessible to those reckless enough to undertake such treacherous journeys; but the roads would also serve another purpose: racing. Well into the 21st century, the Italians are still celebrated for their achievements in motor engineering, which seemingly only the Germans have been able to match and surpass. Like today’s Grand Prix organised by Bernie Ecclestone, the original Grand Prix was never intended to be a modest event. Privileged attendees would be momentarily gripped by the race, although the grandeur of the event as a whole would comprise the main attraction. As with modern-day sporting events such as Wimbledon and the Grand National, image was everything. As well, many sporting fans preferred to obtain news from radios or newspapers in order to abstain from what many deemed pompous vulgarity, in addition to extortionate ticket prices.

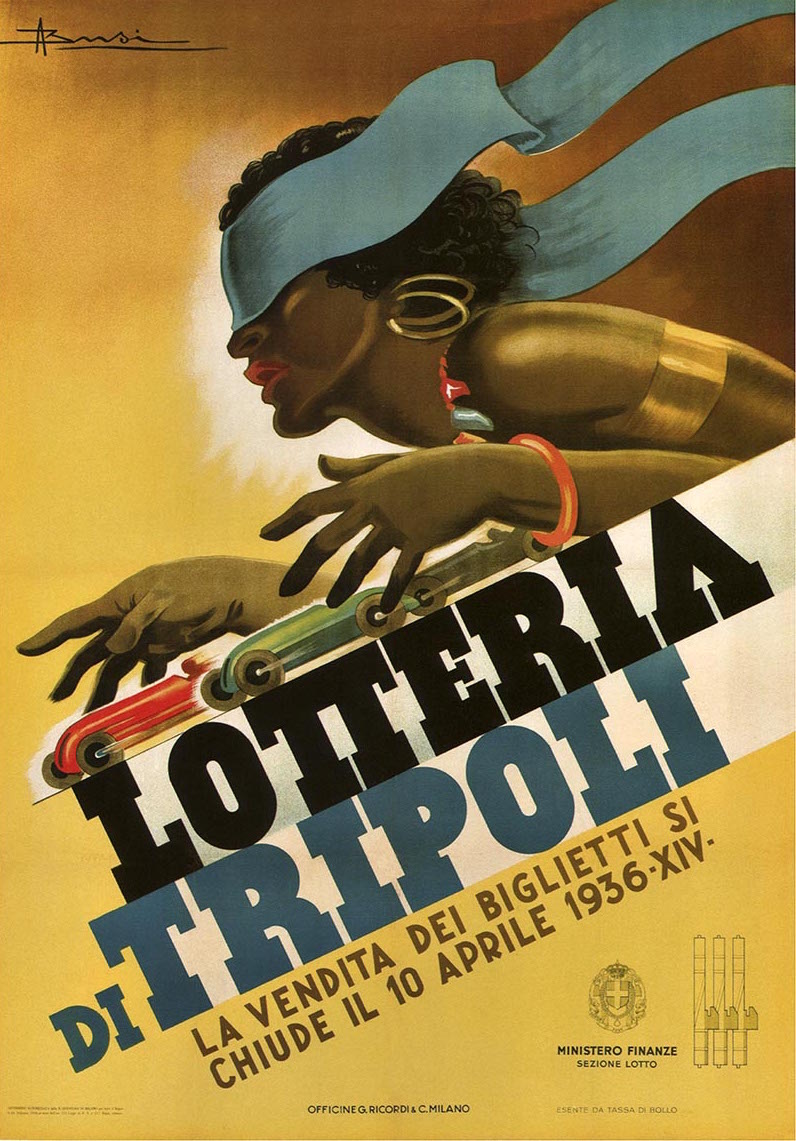

A poster for the 1936 Tripoli Lottery, held in conjunction with the Grand Prix

In 1922, Italy’s Monza racetrack in the north of the country held its first official Grand Prix, which it continues to host annually. Three years later, Africa’s first Grand Prix would take place in Tripoli as a symbol of the colonialist triumph of the Italians. 14 editions of the Tripoli Grand Prix were held between 1925 and 1940, which propagated a colonial ideal to the outside world as Italy refurbished a ‘wretched’ land under the guidance of enlightenment. The backdrop of the Mediterranean coastline, palm groves, and the desert added elements of the exotic to the extravagance of what was once the most happening racecourse on the planet, attracting celebrities, politicians, and race enthusiasts from all over the world. It was not until 1933, though, that the profile of the race was raised with the introduction of a lottery, which resulted in an influx of cash towards the Tripoli Automobile Club. If a ticket was matched with a winning machine, owners could have won up to 7.5 million lire – a hefty sum. For the first time in the race’s history, high-profile drivers were attracted to the Mellaha circuit, measuring 13.1 kilometres. In Valerio Moretti’s book Grand Prix Tripoli: 1925 – 40, the author points out that the race was not supposed to outshine the Fiera Campionaria (the Tripoli Fair) due to the latter’s intended purpose as a commercial bridgehead for the Italian penetration of the North African and Near Eastern markets.

Rudolf Caracciola’s first-place win at the 1935 Tripoli Grand Prix

Italy’s quarta sponda (lit. ‘fourth shore’) harboured wealthy German and Italian tourists during the latter years of the grandiose event, which provided an ideal opportunity for Italy to showcase the wonders of its colony to the rest of the world. Those who attended the Tripoli Grand Prix witnessed the extravagance of Italy’s propaganda efforts to polish the rust of colonialism. Following the race, as Moretti notes,

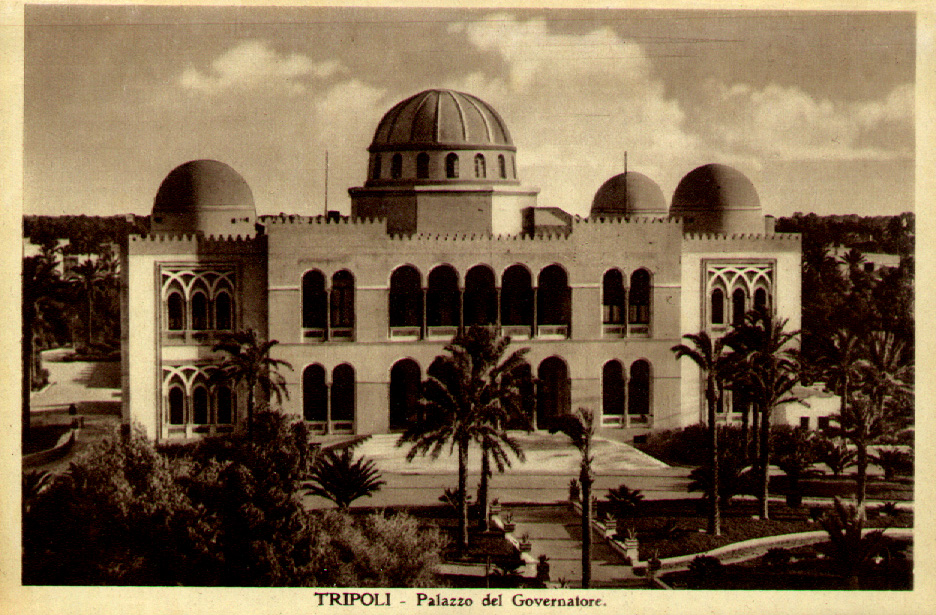

There was the reception at the Governor’s Palace. A fairy story, a tale out of the Arabian Nights [sic.]. African soldiers in gala uniform with drawn swords, the bare shoulders of the women in evening dress, men in dinner jackets or spotless tropical dress uniform, army or civil service, flowers – banks of flowers – fountains and a splendid banquet4.

Tripoli’s Palazzo del Governatore (Governor’s Palace) in a postcard from the 1930s

Within the Italian Fascist party, Italo Balbo (1896 – 1940) was looked at as Mussolini’s successor, on account of his intelligence and charisma. Balbo governed Libya in the colony’s latter years, and was widely respected by Libyans for his moderation in comparison to the approaches for previous rulers such as the ruthless Graziani. Balbo had flown solo over the Atlantic and was a great lover of motorsports. Many say it was he who was largely responsible for the revamp of the Grand Prix in 1933, and describe his arrival and introduction to the drivers as the pinnacle of the race’s history. Shortly afterwards, Balbo would plant himself on a signal tower, where he would remain until all participants had crossed the finish line.

The Mediterranean coastline, palm groves, and the desert added elements of the exotic to the extravagance of what was once the most happening racecourse on the planet …

The final chapter of the Tripoli Grand Prix came just days before Italy entered the Second World War. Italian officers objected to any role in the war, as the outcome seemed inevitable – Italy’s colony would be lost forever. On the 12th of May in 1940, the Tripoli Grand Prix was won by Italy’s own Farina Giuseppe when he crossed the line in his Alfa Romeo at 206.347 kilometres per hour, providing a fitting ending to the race’s grand finale (in Italian eyes), as the previous five races had been dominated by German drivers and cars. Due to the outbreak of the war, the Germans did not participate in the final edition, although many believe they would have won again as a result of their superior engineering.

90 years on from the first Tripoli Grand Prix, not a single F1 race takes place on the African continent, although it continues to be a symbol of prosperity in places like Singapore, Monaco, Abu Dhabi and Bahrain. Tripoli was a jewel in Italy’s colonial crown, but for the Libyan people the days of the occupation were times of degradation. They are not to be celebrated, but not to be forgotten, either. Somewhere around Mitiga International Airport on the outskirts of Tripoli, there were once Maseratis, Bugattis, and Mercedes’ surrounded by saluting fascist mechanics. The shifting sands of Libyan politics have brought the country to where it is today, but rather than brood on the events of the past, one can instead look to history to find hope for the future.

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.

Cover image: Hermann Lang’s first-place victory at the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix.