Women, wit, and whisky - the art of Turkey’s Nazif Topçuoğlu

Having removed his signature Sartre-esque spectacles and reclined comfortably into a plush houndstooth chair, Nazif Topçuoğlu takes another sip from the stout glass of single-malt whisky before him, which, under the glow of the dim, orange potlights above, looks even more sumptuous on this abysmal November afternoon. Had I known he would be drinking, I would have gone for a lager, at least; however, having feared I should appear uncouth, I now have to make do with a tepid latte, the foam of which has an importunate proclivity to settle on my whiskers. The beer here, I soon recall, tastes like donkey’s piss, anyway (as per the Persian expression), so I suppose I’m not missing out on much.

This is my first meeting in person with the architect-cum-photographer, whom the last time I spoke with was likely overlooking a sparkling Bosphorus vista from his Istanbul flat. Only a short while ago, he had told me of his ambitions to relocate to Toronto, and now, interestingly enough, we’ve become neighbours. Upon first glance, he exudes the air of an Anatolian folk-philosopher with his inquisitive gaze and mane that Nazım Hikmet would have doubtless approved of. In his native Turkey, he’s been at times branded a pervert and a paedophile; we’re a far cry from the bustle of Beyoğlu, though, and to yours truly, he appears as anything but. Like countless other Turkish artists whose oeuvres have been questioned and put under a lens in recent years, he’s just – to paraphrase Burdon – a misunderstood soul whose intentions are good; and a very talented one, at that.

Naturally, our conversation begins with all things Istanbul and Turkey. For all my enthusiasm about Turkish culture – literature in particular – and my recent visits to Istanbul in the past year, Nazif seems less optimistic. These days, when discussing Turkey, politics is inescapable, least of all the subject of President Erdoğan, who seems to be the new person everyone loves to hate. As we draw parallels between present-day Turkey and pre-Revolution Iran, I reflect on the visions of Atatürk and Reza Shah Pahlavi, and wonder whether or not they were all in vain; but, as soon as our banter takes on too strong a political flavour for my liking, we return to the crux of the matter: art – and Nazif’s, in particular.

Veruschka von Lehndorff and David Hemmings in Blow-Up

Now in his 60s – a fact he is wont to continually remind me of, remarking with a tinge of sadness every now and then, I’m old, you know? – Nazif initially studied architecture, although he never practiced, quickly turning his attention to fashion photography and wanting to instead follow in the footsteps of Antonioni’s David Bailey-like protagonist in the 1966 cult classic Blow-Up. Since 2003, he has not only exhibited his distinctive photographs in Turkey as well as around the world, but has also authored numerous books (albeit in Turkish), among them the humorous-sounding Photography isn’t Dead, it Just Smells Funny. Spending his time between Canada and Turkey, he is currently represented by Istanbul’s Galeri Nev. However, with the socio-political climate back in Istanbul becoming more and more uncertain, Nazif’s plan is to base himself in Toronto completely. Why? Because things aren’t working as smoothly on the Golden Horn as the artist would like.

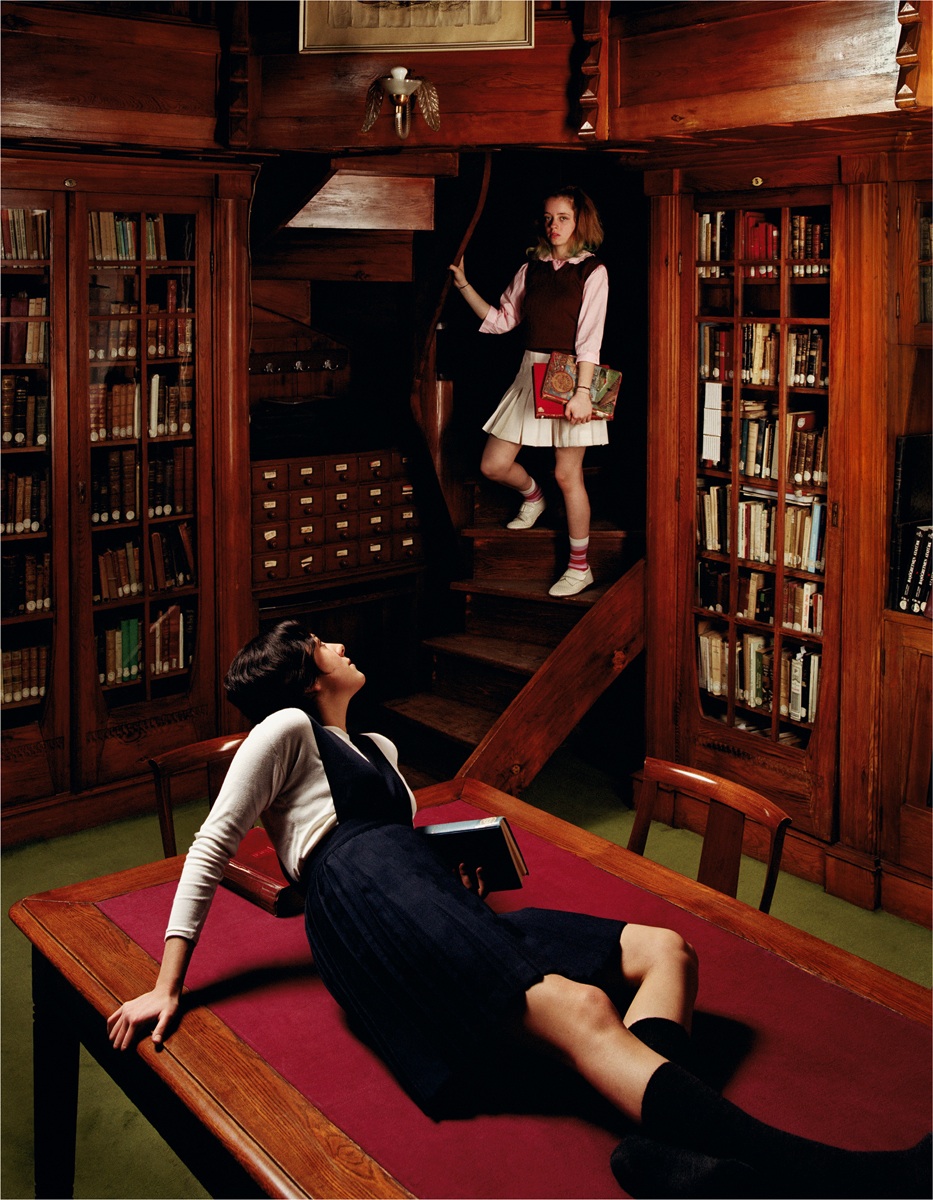

Virgin Suicides (from the A Brave New World series)

Over the years, Nazif has come to be known for his trademark style of photography, which he has mastered in a number of distinct, yet linked series of works. One need not be a connoisseur to spot a Topçuoğlu; Nazif’s works literally scream at one from afar, their recurring subjects, settings, and hues having the artist’s name written all over them. Like some of his contemporary compatriots, such as Nilbar Güreş and Halil Altındere, as well as the Iranian photographers Soody Sharifi and Melika Shafahi, Nazif endeavours to capture dynamic moments in time. These ‘moments’, however, are anything but spontaneous, and rather figments of the artist’s imagination which he tries to translate in physical images from behind his lens. His images are at times surreal, as well sumptuous, in their use of lush and vivid colours and cozy interiors, and are often mistaken for having deliberately sensual and erotic overtones. His subjects are almost exclusively young, attractive girls, often decked out in school uniforms and miniskirts, or other provocative attire, who, to those unfamiliar with Nazif’s outlook, usually seem to be up to no good. ‘People see what they expect to see’, he tells me, before launching into a diatribe about the perverse psyche of some. ‘Turks see a girl in a skirt, and think, let’s fuck!’

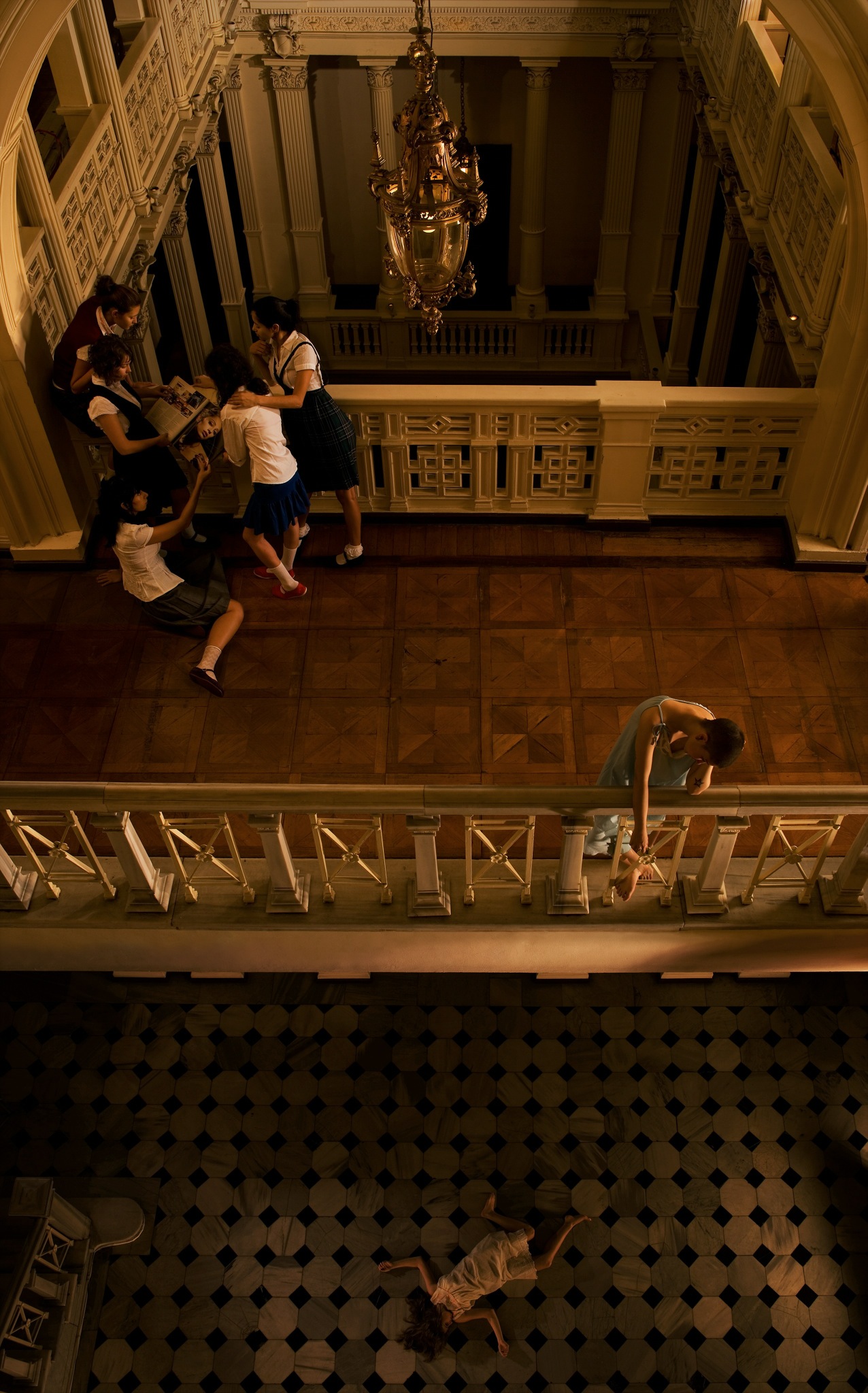

Interview (from the A Brave New World series)

The use of such ‘sexy’ subjects and seemingly suggestive poses is what the artist calls ‘icing on the cake’; in other words, he employs them only to catch the attention of his audiences, rather than add an erotic dimension to his photographs. An only child, Nazif grew up in a house filled with books, always yearning for the companionship of a sister or two. As well, his mother, a prominent lawyer, was an outspoken advocate of women’s rights – not unlike the artist himself today. In many of his works, his female subjects reading books represent Nazif’s libertarian idea of confident, independent Turkish women finding a place for themselves within Turkey and the world at large; or, as the Iranian writer Shahrnush Parsipur might put it, as women without men. Nazif’s series are chronological in a way, and are reflective of sociocultural changes and phenomena particular to Turkey. In his early works, his girls are autonomous and free-thinking, as per one of the dreams espoused by the nascent Turkish Republic in the 1920s; however, as they grow ‘older’, they come to be chastised for their ambitiousness by girls who were once like them, yet, who have conformed to, and settled for a less-than-ideal reality. ‘Girls go to university only to come out and realise there’s no place for them in [Turkish] society’, he laments, further commenting on the reality of a largely conservative and religious Turkish society – ‘It’s not like Erdoğan came from Mars’ – and Atatürk’s failed dream of emancipating women. A work from the artist’s Huxley-inspired Brave New World series perhaps best encapsulates this ‘failure’: huddled in a corner are a group of girls ogling a Western fashion magazine – as opposed to a book – while elsewhere, a lesbian subject (according to the artist) looks down below at her lover, a lifeless mass in a pool of blood: an act of suicide, perhaps, in the face of hopelessness.

You’re always afraid … you have to make sure the girl’s angry brother or father won’t come banging on your door tomorrow

Suicide (from the A Brave New World series)

Despite the fact that almost all of his photographs are taken behind closed doors, and, aside from a work or two here and there, feature no nudity, producing them has often been trying for Nazif. Though still enjoying the status of a secular nation, Nazif is quick to remind me that old habits die hard. ‘You’re always afraid … you have to make sure the girl’s angry brother or father won’t come banging on your door tomorrow’, he tells me candidly between sips of whisky. If only that were the extent of Nazif’s tribulations, though; audiences in Turkey, on the whole, just don’t seem to be as interested in contemporary art – and his, in particular – as he is. As Nazif explains, the majority of Turkish art collectors buy predominantly for investment purposes, or because a certain style of art is in vogue. Due to the shifting political climate, he says, Turkish audiences have become less interested in his work, which, one might argue, provides a stark contrast to the rather conservative narratives being trumpeted by the Justice and Development Party. ‘Turks have a herd mentality … and Turkish artists are so afraid to stray from the norm’. Similarly, though the Istanbul Biennial provided a much-needed kick to Turkey’s contemporary art scene in the late 80s, and the private sector has taken an increasingly active interest in the art world, many would argue that contemporary art still has quite a way to go before it loses the status of an anomaly or a novelty. One need only remember the 2010 riots in Istanbul’s Tophane district, when gallery-goers were pelted with frozen oranges and gassed with pepper spray by an angry mob who found the nature of certain artworks disturbing, to say the least. ‘[Ordinary people] don’t care about art,’ he remarks nonchalantly, ‘and the seculars … they’re so boring’.

Sacrifice - Story of Isaac (from the A Brave New World series)

Though the plan is to finish up the remaining ‘paperwork’ – to use a euphemism – in Istanbul, and eventually relocate to Toronto, Nazif expects no quick ‘solution’ to his difficulties as a Turkish artist; and, judging by his remarks, one can almost say that the worst of his tribulations have yet to come. Although Nazif most probably won’t have to worry as much about the possibility of mollifying peeved Turkish boys on a machismo overdrive in the wee hours of the morning, the fact remains that for all its shortcomings, the Turkish market is home to a large percentage of his potential buyers. While the Canadian market has slowly been opening up to works produced by artists other than those of the proverbial Group of Seven, the latter’s shadows still loom large, and galleries abound with art that is cautious not to stray too far from conventional Canadian expectations. Even though, visually speaking, there’s nothing particularly ‘Turkish’ about Nazif’s works (aside from the odd Persian carpet and Turkish kilim, here and there), the artist still has to deal with the reality that he’s unknown and underappreciated in Toronto, and that gallerists in such a conservative market are – for now, at least – less than enthusiastic about exhibiting his photographs. There’s little to write home about in terms of the scene here, and the city isn’t appealing – particularly to Nazif’s architectural eye – either. ‘The buildings here are so ugly, no?’ Istanbul it ain’t.

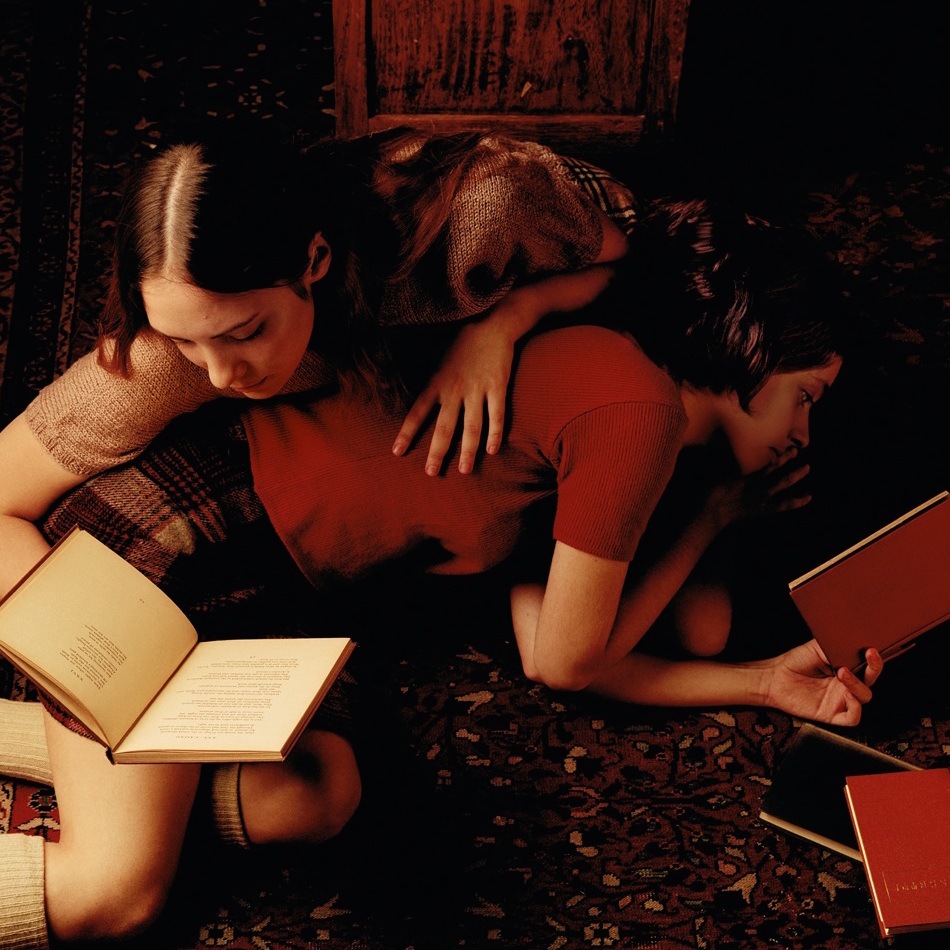

Chance Encounter (from the Readers series)

That being said, though, Nazif predominantly looks at Toronto as a place where he can focus on his practice without the drama of testosterone-fuelled philistines and the anxiety of a Turkey that seems to be increasingly departing from the dream of Mustafa Kemal. Although he is somewhat apprehensive of the future, often making references to his age and the thought of there being ‘little time left’, circumstance hasn’t hindered Nazif in the slightest. Still actively producing work, he has plans for an exhibition focusing on the education of women in Turkey and its gradual decline in the face of a waxing tide of religious conservatism; and, though he has distanced himself physically from Istanbul, he hasn’t by any means cut his ties with the burgeoning art market there, and indeed entertains hopes for future progress in places such as the international art hub that has become the UAE. As well, Nazif also counts the prominent Iranian entrepreneur and museum owner Ramin Salsali among his fans and collectors, and one is pressed to wonder whether the UAE might provide the ideal outlet for his work outside his native Turkey.

Gag (from the A Brave New World series)

Taking a final swig from his glass, Nazif rubs his eyes, brushes back his hair, and places the Sartre spectacles back on his nose. Giddy with whisky, he has to pop down to the loo, yet again. I’m old, you know? he says, laughing, extending a warm, inviting hand. As we part – he heading downstairs, and I outside into a bleak Toronto cityscape – I reflect on all the artists I’ve come to meet in this very hotel. Some were just passing by to see relatives, most likely on their way to the States, while others had come to begin a new chapter in their lives, dissatisfied with the status quo back home. Many have left the city, having come here during the nadir of an unforgiving winter, while the rest have trudged onwards, finding meaning and a place for themselves far away from the slopes of Damavand, the shores of the Bosphorus, and the dusty bazaars of Aleppo. With all his dry humour, fatalism, and resolve, I’m sure the old fellow will do just fine.

All images courtesy the artist. A version of this article was originally published in the March - April 2015 edition of Harper’s Bazaar Art Arabia.

Cover image: Reading Poetry (detail; from the Readers series).