‘Taboos and dark humour come together in this trippy book’

Images courtesy Tamyras Editions

Born in Beirut in 1975, Mazen Kerbaj has published over 15 books, along with numerous short stories and illustrations in daily papers and magazines in not only his native Lebanon, but in Europe and North America as well. Primarily an author of alternative independent comics, he is also a painter and musician. Compressed, Picasso-esque self-portraits have become the trademark of Kerbaj, a leading figure in the Lebanese comics and art scene. When he draws, he pushes the language of comics, and his pictures take on a unique aesthetic quality.

Kerbaj’s artistic fervour can be traced back to his family’s roots. He recently collaborated with his 84-year old mother – the renowned painter and art critic Laure Ghorayeb – for a project with the Beirut-based comic publication Samandal, the first trilingual (English, French, and Arabic) one open to contributors from abroad. Original works by Kerbaj and Ghorayeb were featured in the L’ABECEDAIRE exhibition, which ran between the 11th of March and the 10th of April at Beirut’s Galerie Janine Rubeiz.

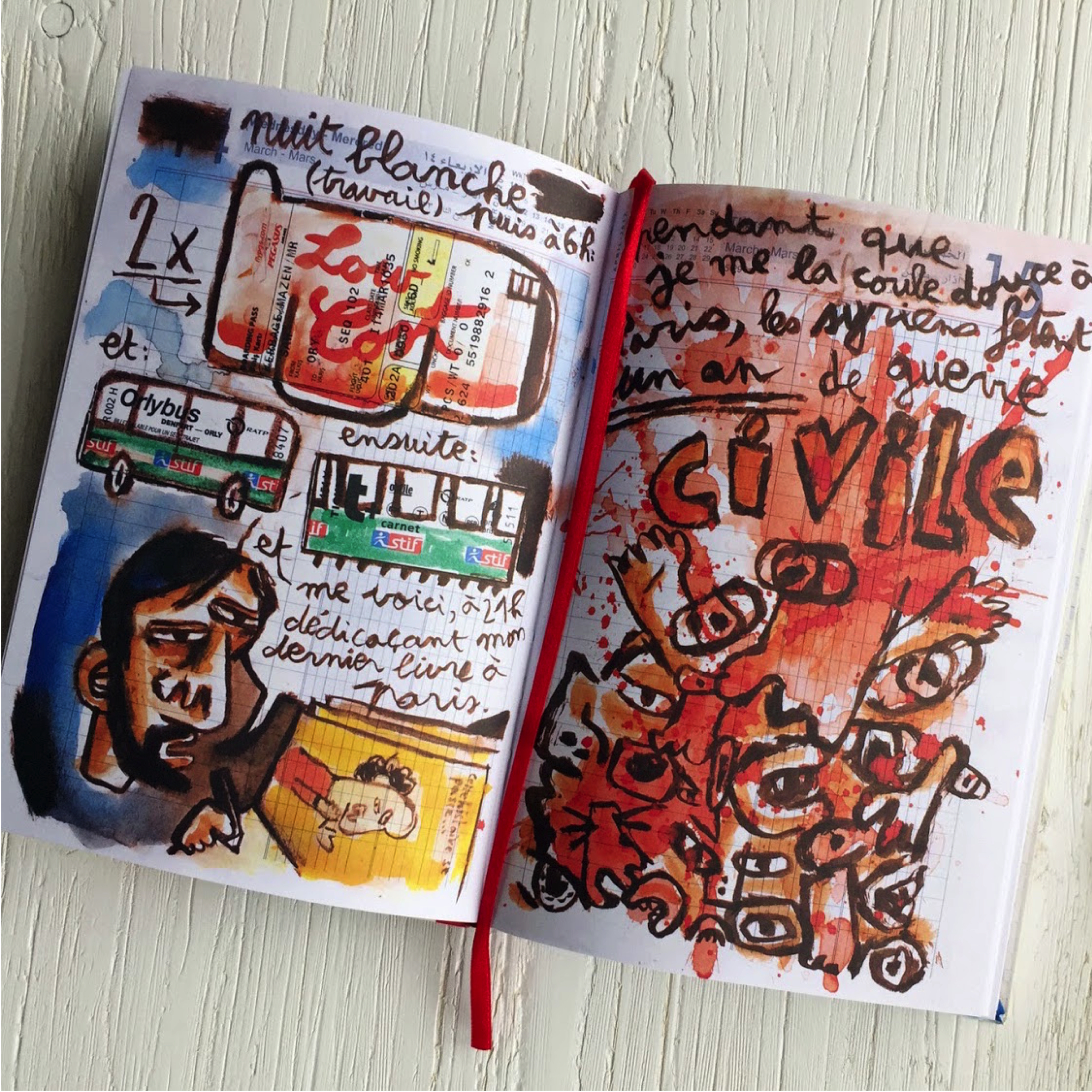

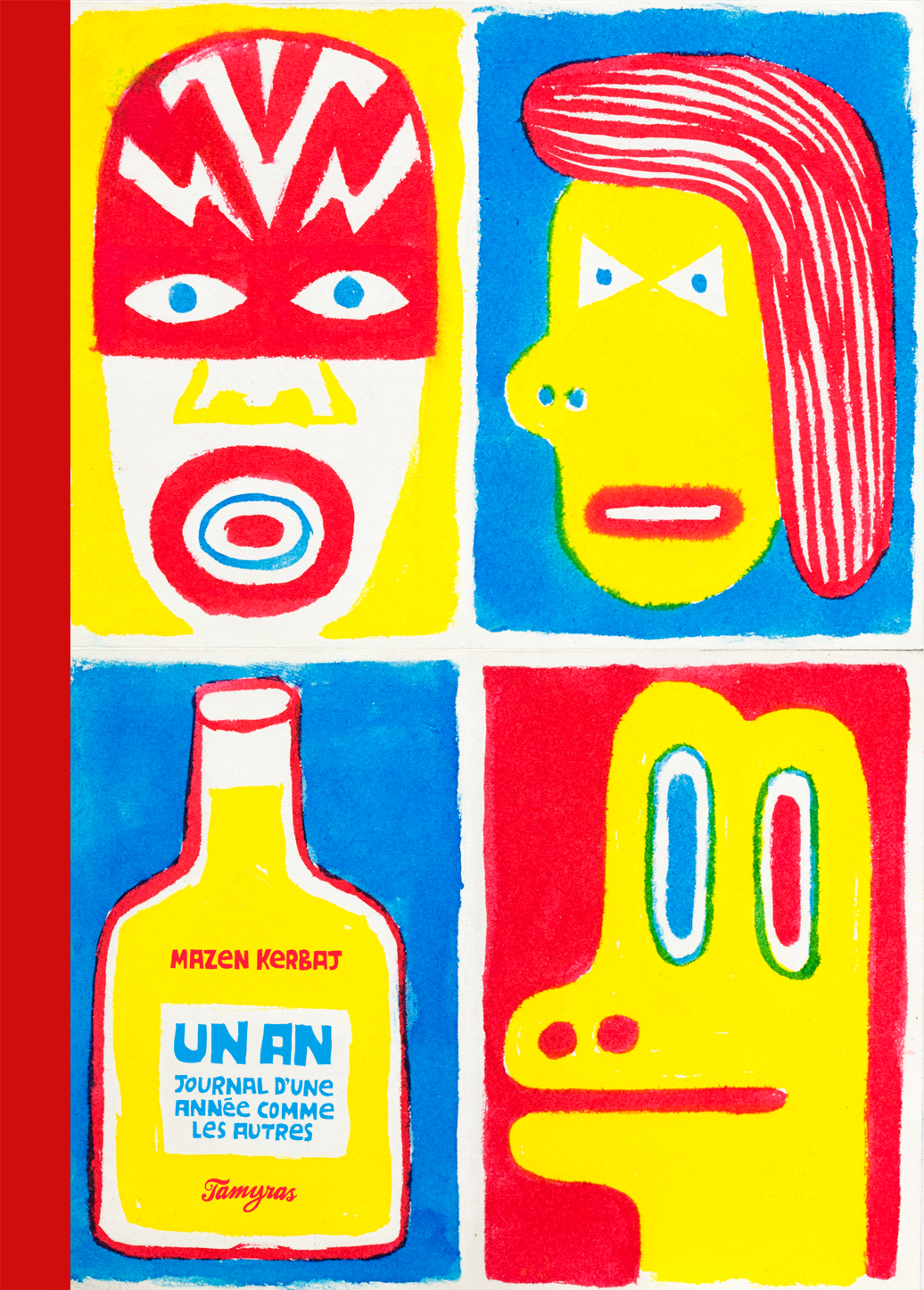

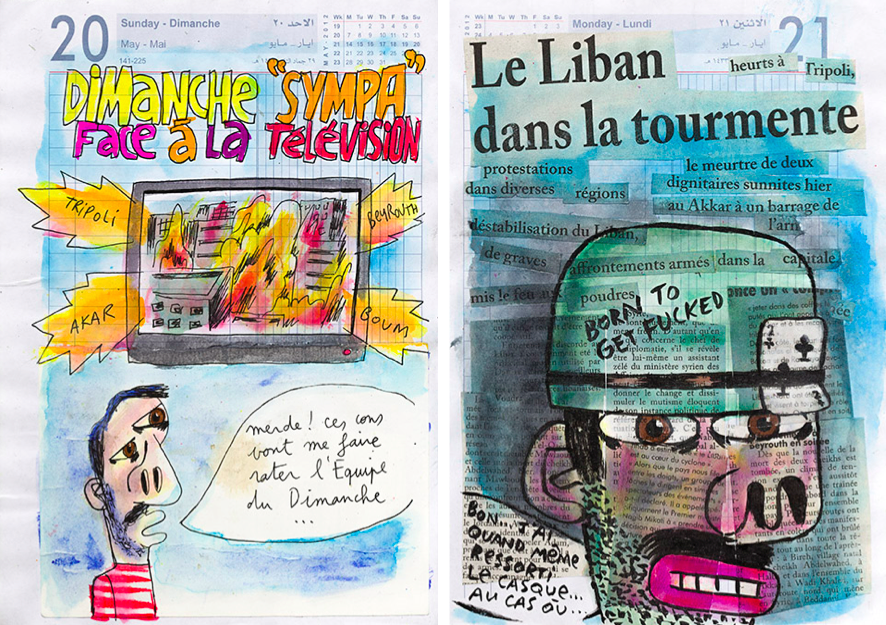

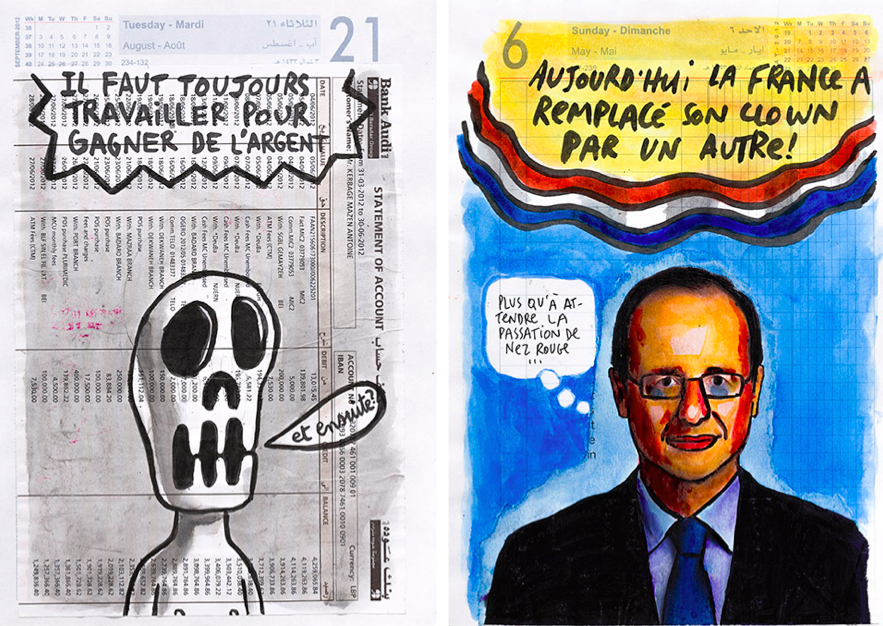

In his latest book, Un An – Journal d’Une Année Comme les Autres (One Year – Diary of a Year Like the Others), published by Tamyras Editions in Beirut in 2014, Kerbaj reveals his extremist habit of drawing. For the book, he challenged himself to expose his life in a collection of 382 drawings executed in a cheap diary, day by day, for the whole of 2012, using a variety of mediums (e.g. ink, watercolour, charcoal, etc.). Some of the illustrations are satirical and touching, inspired by his life in Beirut or his travels abroad, while others are simple chromatic ‘games’ of illustrations on the verge of abstraction. When he recounts his life, he is never self-indulgent, and the result is a picture book with a pop philosophy that is not only a self-portrait of Kerbaj, but also an examination of a range of contemporary issues.

I recently spoke with Kerbaj about his book, as well as his experience as a comic book artist.

From where did the idea for the book originate?

I always liked having a notebook with me (I refer to mine as a ‘portable laboratory’) to test new techniques and colours, and sketch new ideas when I travel. [Later], I decided I wanted to publish one. I started to work on a new sketchbook as a narrating project. In 2012, I decided to [do] a new drawing every day in a cheap diary for a whole year. The works were inspired by my life during that year. Some days, I had no inspiration. Some days, I didn’t want to draw. Other days, I couldn’t stop, and drew [throughout the] night. I published all the works, no matter how good [or bad] they were. The result is not only a collection of comics about Mazen Kerbaj, [but] also a book about the passing of time, a crucial concept in my work. The meaning is personal: time passes, and every year resembles another.

An illustration a day seems like a rather overwhelming task, no?

It could have been, but I’ve never thought about giving up. I am stubborn, and don’t look back. This characteristic suddenly becomes very fruitful every time I decide to start a new project. There was another challenge [instead]. Comics are free to explore sex, drugs, and counterculture in ways that it is not possible [to do so] here in Lebanon. For example, alcohol is not a taboo here. But sex is. Another interesting [challenge] of the book was hot to bypass national censorship and stay authentic. I chose to draw a ‘personal cautionary tale’ that is entirely accessible only to the circle of people around me. Taboos and dark humour come together in this trippy book.

The result is not only a collection of comics about Mazen Kerbaj, [but] also a book about the passing of time … Time passes, and every year resembles another

Music is also another interesting aspect of your career. What’s it like pursuing art and music at once?

I never wanted to be a cosmonaut or a policeman. I knew I wanted to draw when I was five years old, as soon as I learned to flip through the pages of a comic book. Later, I became interested in music. It was my friend and now closest collaborator, Sharif Sehnaoui (who appears a lot in the book), who gave me a trumpet. I was a teenager who had just discovered free jazz and experimental music. He was playing guitar in a group, and asked me to join. It all started as a joke! Then, I started practising every day, and after five years, I could boast a personal style and earn money playing in festivals. But don’t ask me if there’s a relation between doing music and drawing comics: for me, they’re two disconnected careers that I pursue with the same passion and seriousness.

What are three words that would describe your work as an illustrator and comics artist?

I hate style.

Do you have any hard feelings towards the way Beirut has turned out to be in the last few years? It seems like you do in your book.

It’s typical of the Lebanese people to decline all kinds of responsibility. The comics I made for the book on the 18th and 19th of August explain the concept. In those days in 2012, we heard the news of a mass kidnapping. The comics depict my wife, Racha, furiously watching a minister on TV blaming the Lebanese people, because, [as he said], they all have guns at home. I made a quick caricature of the country, and the real situation was more complex. Anyway, this is not the kind of debate you want to see on TV after a mass kidnapping. The public wants to know the truth. I can say that I’m so pessimistic I can’t have hard feelings towards Beirut anymore.

Political drawings have been an important part of your body of work, from your comics protesting the situation in Beirut, to your more recent cartoons criticising the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. Why?

My first published work was for a supplement of L’Orient L’Express, a new monthly political and cultural review founded by the late Lebanese journalist and history professor, Samir Kassir, who was my mentor. I was about 18 years old. A cartoon I posted to protest the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists was [actually] made for Samir, who was also assassinated for his ideas. Sometimes the same comic strips may actually be repeated, without detection, even if you perceive the [stylistic] changes.

Do you feel the need to be cautious during interviews when politics arise?

In satirical drawing, it’s more interesting to put your finger where it hurts! The content of my comics about Lebanon [deals with] social issues and modern behaviour illustrated in a satirical way. I’m careful that they’re not merely provocative, but [are also] conducive to reflection. I think my comics became political when, for example, I drew about the situation in Gaza. In the November 18th entry in the book, you can find some drawings I made for an album created about Gaza in 2008 that I wisely called Old and New Wars. Reposting them in 2012 [was] a way of affirming that nothing changes here.

Do you think comics, stories, and your illustrated metaphors are much better vehicles for your personal opinions than interviews?

If I don’t draw, nobody can interview me.

Cover image courtesy Joe Alam.