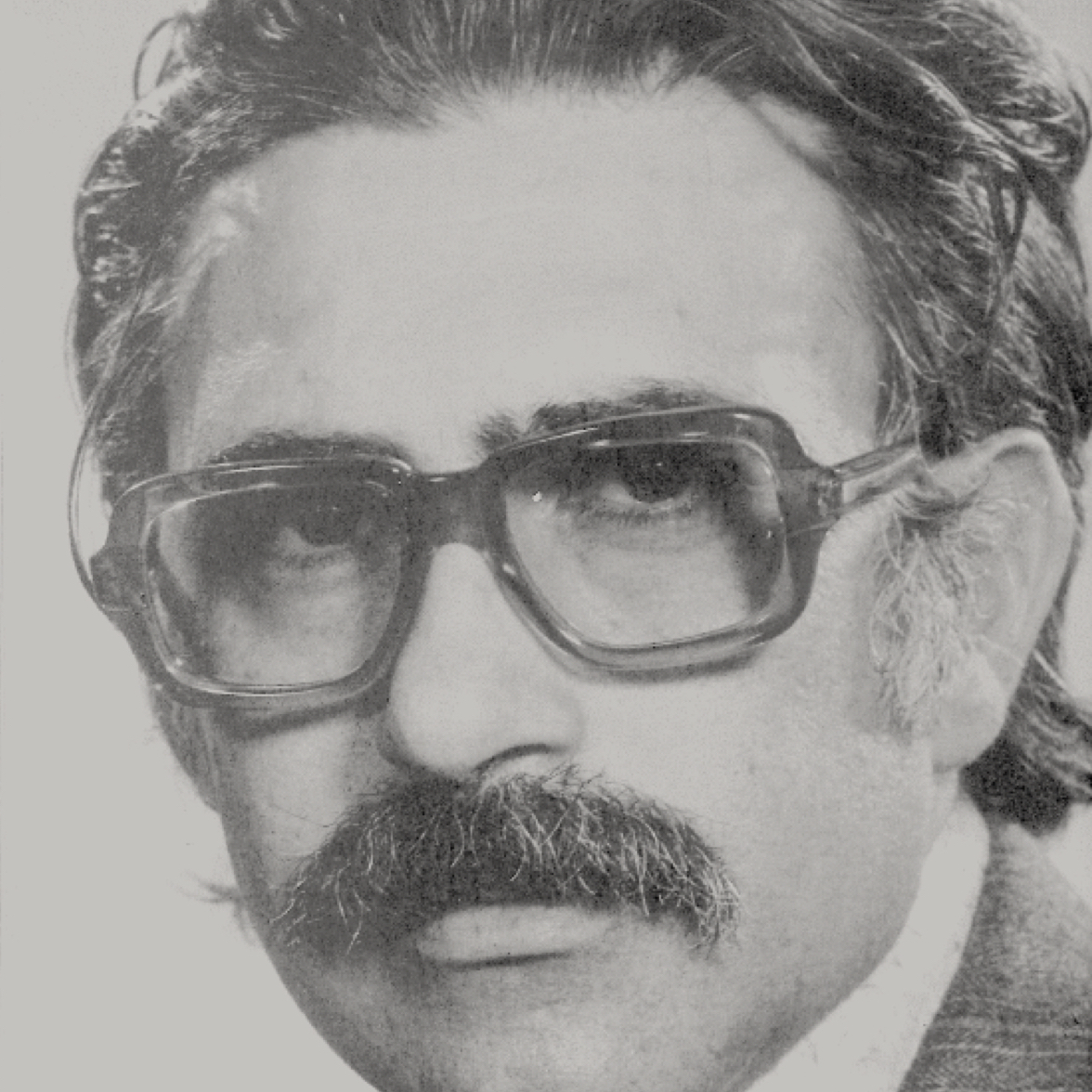

Remembering Karim Emami (1930 – 2005), an ever-shining light in Persian literary studies

The last time I saw Karim Emami was in Tehran; it was March 2004. A few days later, my family emigrated to the United States. I was 18, and passionate about Persian adabiyat (a term that loosely translates to ‘literature’). At the dinner table, Rahim, Karim’s brother, asked what field I wished to pursue. It was an intimidating question. Karim and Goli were my mom’s ideal couple; the two were an intellectual powerhouse. I’d hear about their literary translations and interviews, and about Zamineh, their bookstore and publication house, which remarkably became, in its short life, a regular gathering place for writers and members of the literati in Tehran. During our last meeting, Karim gave me a copy of his newly-published translation of Sohrab Sepehri’s poetry, The Lover is Always Alone. ‘Fani, right?’ he asked me, before signing it. Elahiyeh, Nowruz of 1383, he wrote. Little did I know that Karim was to leave us only a year and a half later.

Leaving Iran was the beginning of my personal relationship with Karim and his wife, Goli – a relationship no longer mediated by my mother, Karim’s cousin. In California, I began to read his literary translations: Gatsby-e Bozorg (The Great Gatsby), the Rubaiyyat of Omar Khayyam, and selected poems of Sepehri, Forough Farrokhzad, and Abbas Kiarostami. Az Past o Boland-e Tarjomeh (The Lows and Highs of Translation), his writings on the problem of literary translation, written with his distinct light-hearted humour and unmatched precision, was my introduction to the critical discourse of translation and literary studies. Attempting to emulate his style, I began to break my long sentences and articulate complicated ideas with more clarity. Meanwhile, I had begun writing to Goli. I shared my literary preoccupations with her, and frequently sent her writing samples. In her prompt responses, she was brief, blunt, and insightful. Above all, she was demanding. She might as well have signed her emails, Read, read, read; she still does. After reading each email, I would look forward to our next conversation. I still do.

After earning my bachelor’s degree in comparative literature, I moved to Latin America to teach English. I returned to the United States to pursue a Ph.D. in Persian literature. In the past decade, our correspondence has only grown. After each conversation, Goli sends me numerous references. Since I have not travelled to Iran for several years now, she has had to mail books as well. It has not always been an easy task. Sending books from Iran to Mexico was difficult – she had to mostly send PDF files; and, in the US, the postal service has been opening all packages from Iran. The last time I received a package, they forgot to reseal it, and two of her books were permanently lost. Over the years, Goli has generously put me in contact with a wide network of publishers, scholars, critics, and poets in Iran and around the world. Her vision and kindness have made the distance between California and Iran bearable. Karim and Goli have both mentored me in different ways; they did, and have done all any literary student could ever ask for.

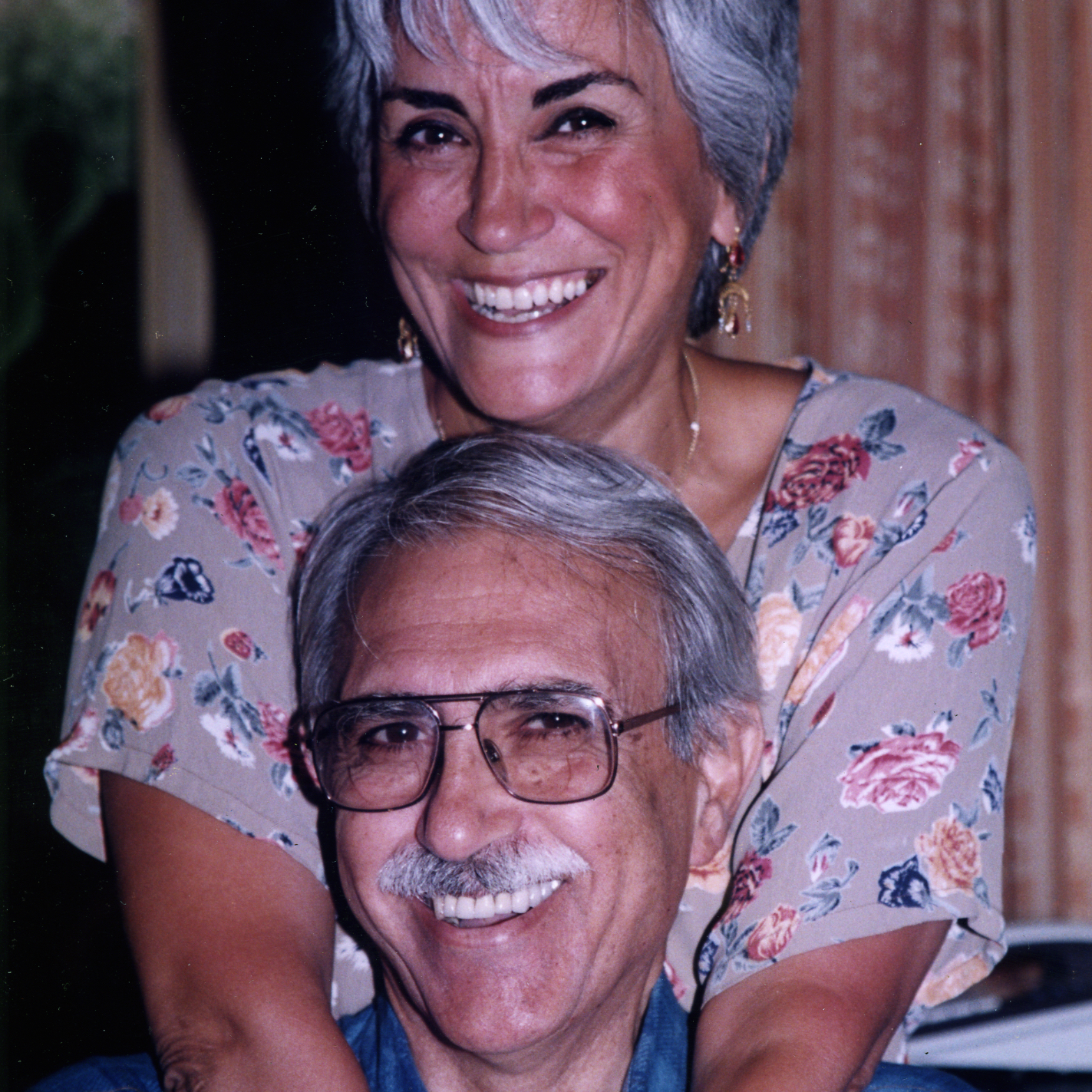

Karim and Goli Emami (courtesy Goli Emami)

In 1962, Karim joined the Tehran-based English-language daily Kayhan International. He had previously worked as a photographer, filmmaker, and journalist, and held a master’s degree from the University of Minnesota in English language and literature. Kayhan International was read by a marginal number of English-speaking Tehranis, as well as foreigners residing and working in the country. During his years at Kayhan (1962 – 1968), Karim rose to prominence as a leading cultural observer and literary commentator. He was among the first to translate the work of modernist Persian-language poets and fiction writers into English. A selection of his English-language columns on Persian fiction, poetry, plastic arts, theatre, cinema, and painting has recently been compiled by Goli, edited by Houra Yavari, sponsored by London’s Iran Heritage Foundation, and published by the Persian Heritage Foundation in New York City. Prefaced by Shaul Bakhash, the collection is entitled Karim Emami on Modern Iranian Culture, Literature, and Art, and was launched at the 10th biennial Iranian Studies Conference held last August in Montréal. The publication of this collection is a significant contribution to cultural, social, and, in particular, literary studies of contemporary Iran.

The critic and its participation and voice have been underexplored in contemporary Persianate literary culture, and the publication of Karim’s collection helps illuminate such voids

The period between the 1940s and 1970s saw the development of a new literary culture, which historians have referred to as ‘committed literature’. This culture was broadly based on the core belief that any literary work must reflect sociopolitical preoccupations and champion a particular cause. Although reduced to general trends and tropes by episodic readings, literary commitment, both in theory and practice, is an ongoing and multifaceted debate. It has looked to different sources and traditions, cultivated different voices and visions, and had myriad tools at its disposal. Unsurprisingly, the canonical history of poetic modernism in Persian is intertwined with committed readings. Such readings attempt to locate particular sites of struggle, and, consequently, promote a limited circle of poets (and critics), mostly leftists. At worst, such a framework marginalises poets whose oeuvres do not lend themselves to committed readings, and, at best, renders them standalone figures.

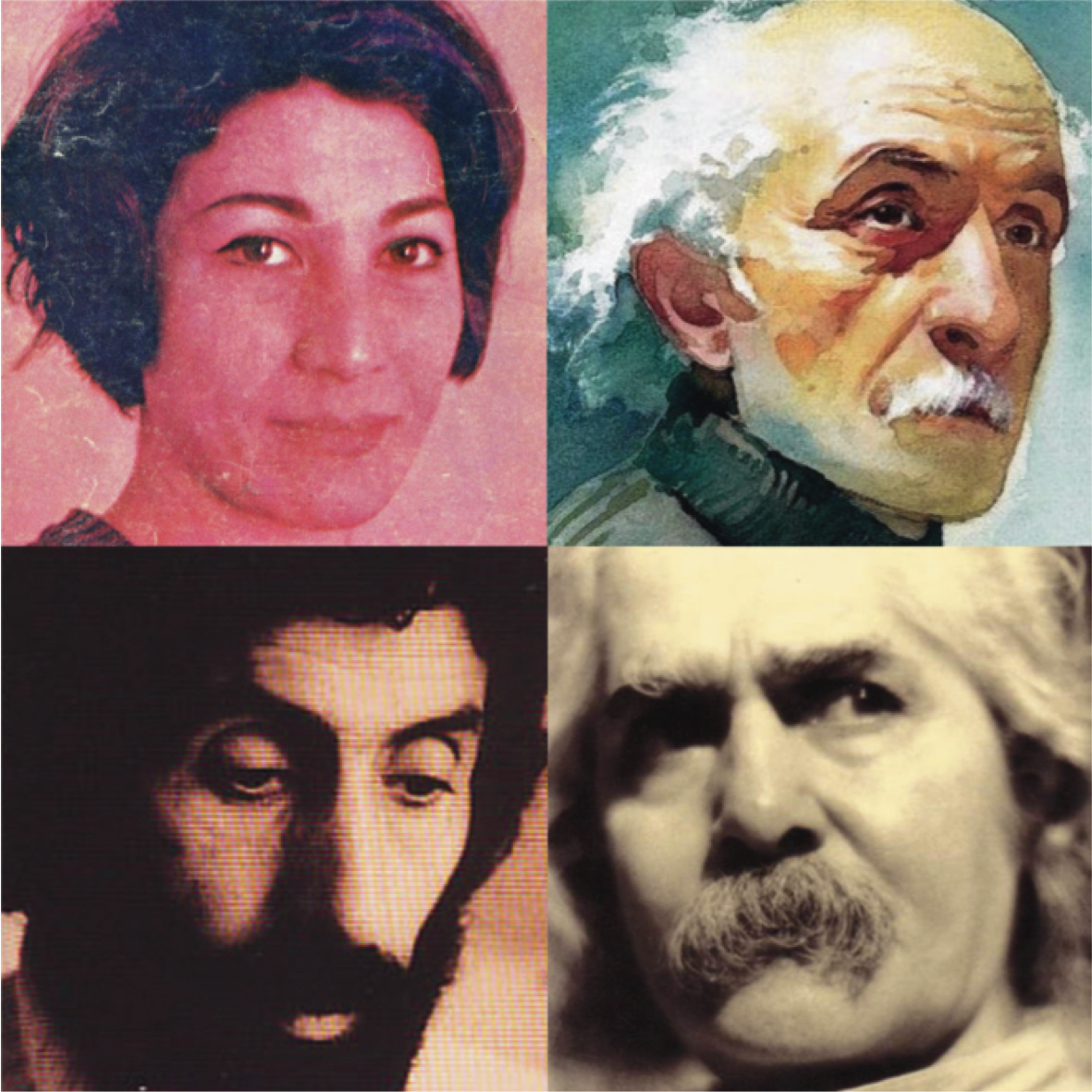

Modernist Persian poets (L-R: Forough Farrokhzad, Nima Yushij, Sohrab Sepehri, and Mehdi Akhavan-e Saless)

Contrary to what such accounts argue, the literary scene of 1960s Iran was marked by highly diverse and dynamic conversations on a number of compelling and open-ended questions: what does it mean to be a poet? What does it mean to be a politically-committed poet? On what levels does poetic modernism rest? The discovery and examination of literary debates counter such reductionist narratives, and the role of the critic in the development of poetic modernism is vital. The critic and its participation and voice have been underexplored in contemporary Persianate literary culture, and the publication of Karim’s collection helps illuminate such voids.

In 1963, Karim penned an article entitled New Horizons in Persian Poetry, offering what he called a ‘limited and arbitrary’ sample of contemporary Persian poetry. Mentioned in the piece were Nima Yushij, Fereydoun Tavallali, Nader Naderpour, Ahmad Shamlou, Mehdi Akhavan-e Saless, Forough Farrokhzad, and Sohrab Sepehri. Apart from Nima, the poets – all of whom are now canonical figures of modern Persian poetry – were then in their 20s and 30s. In his diverse selection, Karim included a variety of approaches to form, content, music, and rhyme. At the end, he acknowledged that he had left out other ‘modernists’ in the field. In this short piece – as with all his articles – Karim gave a glimpse into the world of writers and poets whose unique routes – artistic, ideological, and personal – made up a major part of poetic modernism in Iran. Literary modernism is at once a selective and ongoing process; it is not imported or exported. The history of poetic modernism in the Persianate literary tradition has yet to be written across its wide world of politics and poetics, and illuminating the artistic milieu of 1960s Iran is a positive step in that direction.

Karim left Kayhan in 1968 to become the English-language editor and cultural director of the Franklin Publishing House (Mo’asseseh-ye Entesharat-e Feranklin). His own routes took him across many lands – Calcutta, Shiraz, Tehran, Paris, Minnesota – and now, with the publication of this collection, will take him to wherever his new readers may be.