Dreams, decrepitude, and despotism - Kader Abdolah’s new novel about the life of a legendary Iranian monarch

Kader Abdolah’s life is no less unusual than his fiction. Born to a deaf-mute father belonging to Iran’s down-at-heels aristocracy, Abdolah was an active member of the revolutionary left in his youth. In the mid-1980s, he fled his homeland for Istanbul, before arriving in the Netherlands as a political refugee. At 34 years old, Abdolah spoke not a single word of Dutch, though he was determined to make his way as a writer in his adopted country. ‘I was really powerful, I knew everything in Persian literature,’ says the author in a biographical essay, ‘and suddenly I came to the Netherlands, and I was not able to talk’. By his own account, Abdolah’s first story in Dutch was a mere 700 words long, and contained some 2,000 mistakes. Its prose was a self-made pidgin with the charm, one might imagine, of wooden clogs.

Known today as a master stylist in Dutch, Abdolah is a best-selling author whose works have been published in more than a dozen languages. His previous two novels translated into English, The House of the Mosque and My Father’s Notebook, both of which take place in the decades before and after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, marked the debut of a unique voice in contemporary fiction which draws together — in an admixture of genres — the realist novel and Persian storytelling traditions.

Like many writers in exile, Abdolah’s novels are about looking back onto what he has lost, and making sense of his homeland’s recent and troubled past. Abdolah, though, sees that past as a country filled with mystery, and all his novels take place in an enchanted, almost magical world. In My Father’s Notebook, which set the tone for his subsequent books, the exiled narrator, Ishmael, in seeking to understand not only the loss he has suffered, but also the whole sweep of Iran’s bloody history, finds that his quest to decode the incoherent jottings of his father (the deaf-mute son of a Persian nobleman, incidentally) leads to Saffron Mountain. The legendary pile of rocks overlooks the family’s village, and stands for nothing less than a country’s ‘spiritual legacy’. As the moon pulls the tide, the mountain — and the myths and memories it conceals within its walls — holds a deep psychological power over the present.

That metaphorical mountain overshadows all of Abdolah’s fiction. In the simple and direct prose of a fairy tale, Abdolah presents a wonderfully original treatment of the historical troubles that have plagued Iran in the past century and a half. Perhaps unexpectedly for a former leftist and revolutionary, Abdolah brooks no Manichaean simplicity in writing about that past — nor could he, because his tales are, finally, about something far more subtle: the power imagination holds over reality. They are stories about stories, enchanting readers in the beguiling style of the Thousand and One Nights.

A dark and humorous tale about 19th century Iran, The King loosely takes for its model another Eastern classic, Ferdowsi’s 11th century Shahnameh (Book of Kings), Iran’s national epic, which celebrates the glories of Persia before the Arab conquest in the seventh century. Like the medieval bard himself, Abdolah plunders history for inspiration, freely mixing fable with fact in his retelling of the life of Nasereddin Shah, Iran’s longest reigning monarch in the Qajar dynasty and almost an exact contemporary of Queen Victoria.

At the high tide of European imperialism, Abdolah’s king, ‘Shah Naser’, rules over a once-magnificent land that has become a poor and backwards country of beggars. He hopes that the modernising reforms of the vizier, Mirza Kabir, will restore Persia’s former power and help him win back land from the English and Russians. But the overweening vizier becomes too ambitious for the king, whom he frightens with talk of waking ‘the people from a thousand-year old sleep’ by building railroads and writing — of all things — constitutions for the good of the country.

The king, who comes to bitterly regret murdering his vizier, is weak and constantly doubts his own decisions, but is never wholly loathsome. Perhaps that is because he spends so much time whispering secrets to his cat, Sharmin — the only companion he trusts — and writing sentimental lines of poetry. Naser casts about for guidance and expression in Hafez’s Divan, the Koran, and other ancient tomes, sprinkling the story’s prose with poems and medieval tales that not only heighten the psychological drama of the king’s struggles (he fantasises about living as a humble, well-fed peasant), but also foreshadow and suggest how readers might feel about events. It is part of Abdolah’s storytelling talent to have his audiences pause and look around, to set and slow the pace as he pleases, before showing them on their way.

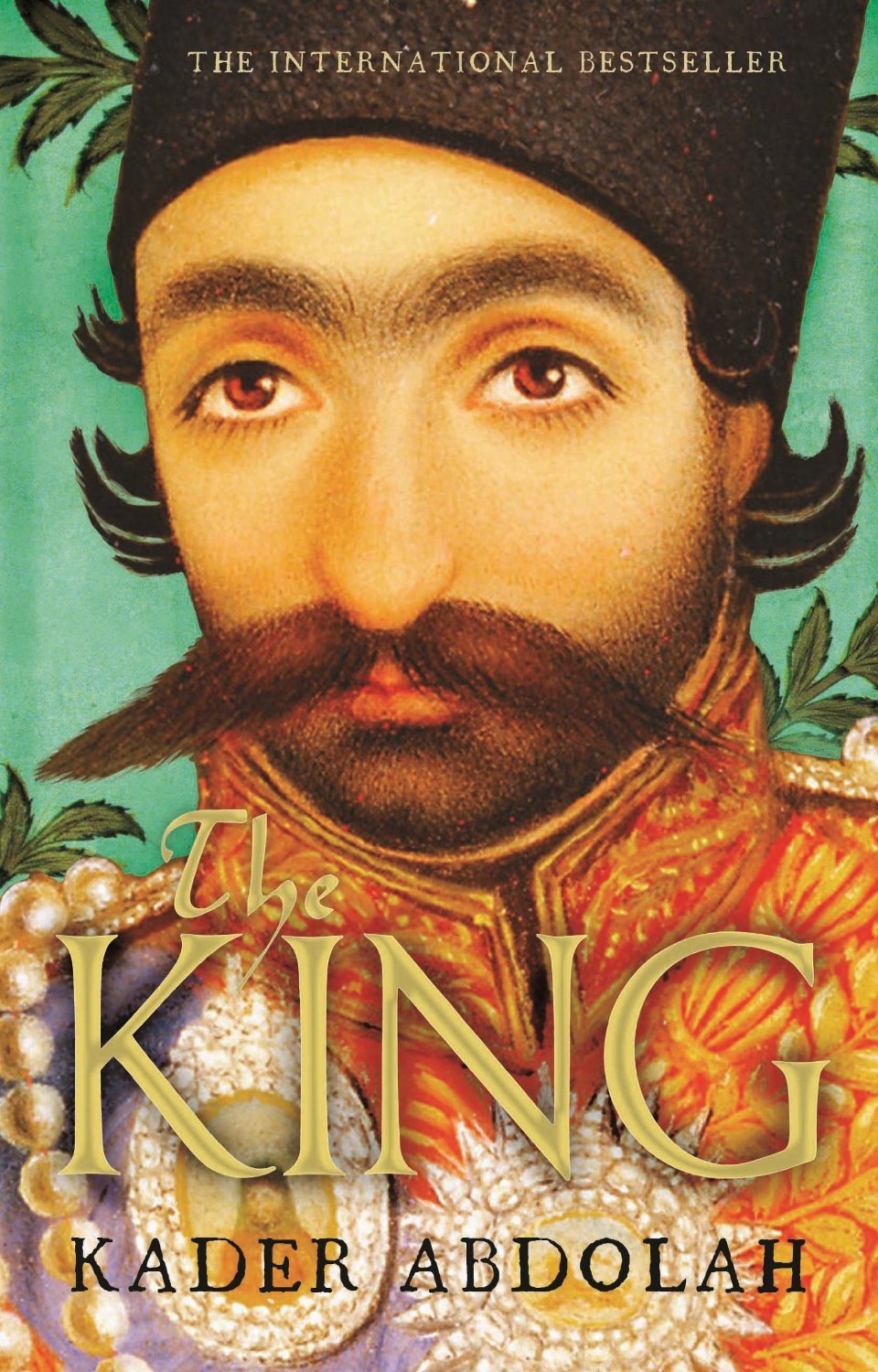

A portrait of Nasereddin Shah by Mohammad Esfahani (c. 1850s)

Like the king — who is a tyrant, albeit a very sympathetic one — Abdolah’s characters are true to type, but rarely flat. Ever the shrew, the queen mother, Mahdolia [sic.], is a strangely compelling figure, perhaps because she follows in a long line of women in Persian literature, who, reared in a deeply chauvinistic society, had to be twice as strong as their menfolk to survive. Believing that she is all that stands between her son and the kingdom’s ruin, she constantly tells Naser to rule with an iron fist. ‘Someday they’ll know who I am’, she tells her reflection in the mirror, ‘I know all the women of Persia, those who are among the living, who still exist, and those who no longer exist. All the power and all the rights that have been taken from women are now mine.’ Yet, the very idea of that Scheherazade-like power has corrupted her and her own story. And, while Mahdolia defends herself with talk about the Nights (why build factories and schools when the king already lives in magical gardens?), it becomes clear that the old tales, and the traditions they signify for her, are justifications for blind tyranny in her deft hands; Abdolah, in other words, sees wanton ignorance, as well as beauty, in the old ways.

Abdolah’s fiction possesses an allegorical power not found in any history or journalism, unlocking the secrets of a people’s pathos and memory with childlike clarity

While the plot meanders a little after the vizier’s death, the unsettling effects of modernity add new excitement to the story, and an opportunity for Abdolah, in his typically epigrammatic style, to reflect on the differences between the East and the West. Sitting with the king, Pirnia, a young, liberal-minded businessman who has lived in Europe, explains the difference between stories in the two cultures:

Although the East is known for its secrecy and we are the masters of mysterious tales, the West also has something we lack. In the East the secret lies in the past, in books, in our narratives and behind our curtains, but the Europeans have made the hidden things visible. There the secret things can be touched. You can even sit in them. Take the train, for instance.

It is fascinating how comfortably such pronouncements fit within Abdolah’s work, leaving little room for chatter about the ‘Other’ and Orientalism. The East is ancient, spiritual, and backwards; the West is modern, materialistic, and far more powerful. They ring true because, after all, many Iranians themselves saw things like that in the late 19th century.

Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria’s youngest son (centre), with Nasereddin Shah on his first trip to Europe

Refreshingly, Abdolah is matter-of-fact about the technological wonders of the West, and the awesome, disruptive power its ‘machines’ exercised upon lands whose material culture had changed little for a millennium. In The King, these machines, imported from Europe, slowly transform the interior, imaginative life of a fairytale land. Peasants gawk at telegraph poles spreading across the country, while birds must recover from the shock before comfortably perching on the wires. Popular desire for a national telegraph inevitably leads to revolutionaries knocking on the doors of the king’s castle, demanding accountable leadership.

For Abdolah — the pen name of Hossein Sadjadi Ghaemmaghami Farahani — his latest novel’s choice of subject is personal. The book is dedicated to his ancestor, Mirza Bozorg Ghaemmagham Farahani, the early 19th century vizier whose family supplied many of Iran’s best statesmen, including Amir Kabir, the adopted son of a cook, who became Nasereddin Shah’s tutor and vizier. Amir Kabir, like his counterpart Mirza Kabir in the novel, energetically set about building canon foundries, factories, and modern schools; many Iranians still revere him as a nationalist leader whose courage — as with so many heroes in the Persian tradition — cost him his life.

Iranians have a way of revisiting the same few historical traumas, citing Amir Kabir’s murder alongside Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh’s overthrow in the American-backed 1953 coup (which provides the backdrop to political radicalisation in The House of the Mosque) as the two events foreordaining Iran’s miserable fate in the 20th century. While such widespread idées fixes can be tiresome, Abdolah’s fiction possesses an allegorical power not found in any history or journalism, unlocking the secrets of a people’s pathos and memory with childlike clarity: a vital point that critics, who blame Abdolah for his fast and loose ways with the actual record, often miss.

Nasereddin Shah and his attendants at the Shahrestanak summer compound (photograph by Antoin Sevruguin, from the Myron Bement Smith Collection, courtesy the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery archives)

In The King, what is more important than the aforesaid is Abdolah’s relationship with a literary, even mythical past. He does not treat that inheritance with the full-hearted iconoclasm of mid-20th century writers —who regarded the Persian canon with a kill-your-darlings attitude — but invokes the old legends as his muses. Even when gently satirical, Abdolah evinces a deep respect for his own tradition as something alive: an ancient tree that, with only a little pruning and grafting, can give new fruit. For Persian speakers, his voice clearly recalls the genre of children’s folktales opening with the line yeki bud, yeki nabud (‘there was one, there was no one’), the Persian equivalent of ‘once upon a time’.

Torn between two worlds — one past and the other only beginning — Naser’s story is not only the swan song of Oriental despotism, but also stands for a country’s struggle to keep a sense of self at a time of rapid change

With the calm, quiet, and wondrous tone of those childhood tales, Abdolah draws out not only the underlying strangeness of the world, but also the underlying pull of a storyteller’s past — one that guides him, as a writer, towards a sense of self in the present. He is one of many Iranian novelists moved by what the Iranian writer Shahrnush Parsipur has called the ‘historical imperative’ for her generation to put pen to paper as the most meaningful way to make sense of a century’s political upheavals and the sudden, almost surreal transformations suffered by a country in such a short time. At the end of Abdolah’s previous novel, The House of the Mosque, Shahbal, a character whose fate follows the author’s own, sends a letter from his exile in Holland. He tells his father that,

… Writing has been my salvation. It was the only way I could express the suffering and pain that you and our country have undergone. Even though I write in a new language, I still try to imbue my stories with the poetic spirit of our ancient and beautiful language.

Nasereddin Shah sitting on the Peacock Throne (Takht-e Tavoos) in the Golestan Palace in 1880 (photograph by Antoin Sevruguin, courtesy the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery archives)

This is Abdolah’s historical imperative, and that of many writers in exile: confronted by the sheer depth of loss, their fiction brandishes a recovered heritage, reworking its traditions into contemporary forms. Less than a century after the first modernists in Iran, émigré writers have taken the literary project full circle.

The King finds an unusually rich subject for fictionalisation in the actual Nasereddin Shah, who was an author in his own right, having written several travelogues that pioneered a concise prose dispensing with classical Persian’s courtly embellishments. The Shah may have even penned stories faintly similar to those of Abdolah: Tehran publishers have attributed to the royal hand the late 19th century Tales of the Old and the Young, among the first collections written in the modern European style that drew on the leitmotifs of Persian folktales.

History has not been kind to the Qajar kings, mocking them as feeble warriors and hopeless sybarites, though they presided over a national revival in the arts and literature. Fancying themselves the heirs of Ferdowsi’s kings, the Qajars were enthralled by the old legends, commissioning countless royal portraits and their own dynastic epic, Tales of the King of Kings. Conflating his life with the fictional realms of ancient Persia, a young Nasereddin Shah also commissioned a gorgeously illustrated copy of the Nights, showing himself as the story’s prince, with scenes from his early life set alongside the original tales. Poignantly, the king and Amir Kabir are depicted as the Abbasid caliph Harun Al Rashid (born and buried in Iran) and his grand vizier, Ja’far the Barmakid, whose story of mentorship and betrayal exactly mirrored theirs.

An 1854 depiction of Nasereddin Shah by Hassan Ghaffari

Beleaguered by the imperial ambitions of Britain and Russia, and finding the reality of kingship a good deal less grand, Nasereddin Shah in his latter years scribbled his frustrations in the marginalia of official documents, lamenting his powerlessness in the face of colonial aggression. ‘Are we puppets made of wax? In this world there are no human beings like us’, he once wrote. Abdolah’s Shah Naser, while pouring his heart into his poetry and own writing, is almost the opposite of the traditional princely figure, who appears as almost the only character endowed with anything resembling agency in Persian literature. The romanticism of Persia’s past, filling the king with hopeless dreams, does nothing but underline his own impotence, even as he grows into a mean and conniving tyrant with age, enchanted with the fiction of his own power.

Torn between two worlds — one past and the other only beginning — Naser’s story is not only the swan song of Oriental despotism, but also stands for a country’s struggle to keep a sense of self at a time of rapid change. Adding a ‘flicker of hope’, Abdolah gives his novel a fairytale ending, in which the country lives happily ever after under a new king and a constitutional monarchy. It is a symbolically powerful and — as the narrator confesses — counterfactual fantasy of a nation that manages to balance the ancient with the new.

But Abdolah hasn’t entirely shed his revolutionary attitudes. The King is not only about the passing of the old world — going out with a long sigh and an assassin’s bullet — but the promise and liberations of the new. Between the two, it is about the endurance of an idea — Iran — a country that, for the medieval poets like Ferdowsi, was as much a literary place as it was a land and a people. Perhaps more than kings and revolutionaries, Abdolah’s homeland has always belonged to the imagination of poets and storytellers.