The allure and enduring legacy of Persian nasta’liq calligraphy

When the famed calligrapher Mir Emad was murdered at the Safavid court in 1615 – perhaps on account of artistic rivalry or perhaps because of his religious affiliations – an important chapter in the history of the calligraphic script known as nasta’liq came to a close. Mir Emad was not the originator of nasta’liq, which emerged in 14th century Iran as a likely marriage of two other styles (naskh and ta’liq), but he was nonetheless largely regarded as its undisputed master, attracting admirers among his Safavid patrons, Mughal emperors in South Asia, and countless others even long after his death. His demise brought to end a prolific period of nasta’liq production that witnessed the rise of an unknown script to one heightening the sensory reception of Persian verse to an artistic end in itself, often overpowering the meaning of the texts it was used to write with its visual appeal. In but a few centuries, nasta’liq had triumphed as the premier style for artfully presenting the words of poets and authors writing in Persian, both major and minor (in addition to occasionally being used for Ottoman Turkish, and in rare instances, Arabic). This rich period in the history of the script, the study of which is at times relegated to an afterthought compared to other Persianate arts such as poetry, painting, and architecture, is the subject of a new exhibition entitled Nasta’liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. On display there are single folio pages and books featuring examples of nasta’liq in jali (large) and khafi (minute) scripts, as well as the calligraphic implements employed, making for an altogether admirable overview of a script that shot across the Persianate world between the 14th and 17th centuries and set the artistic standard for Persian calligraphy.

The Genius of Persian Calligraphy charts the emergence and proliferation of nasta’liq through the exploration of four of the style’s most preeminent exponents: the presumptive inventor, Mir Ali Tabrizi (active between 1370 and 1410); the exemplar of the classical style, Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520); the large-format specialist, Mir Ali Haravi (d. 1550), and the aforementioned Mir Emad al-Hasani (d. 1615). Each of these calligraphers’ artistic output mirrors an important phase in the development of nasta’liq, and lends insight into a specialised world of calligraphic expression. Beginning with the mastery of Mir Ali Tabrizi, whose talents and instruction led to the consecration of a number of selselehs (lineages) in eastern Iran and beyond, and continuing onwards to the peerless works of Mir Emad at the court of Shah Abbas the Great, the exhibition considers how the calligraphers honed their skills through long hours in their ateliers and raised nasta’liq to the highest reaches of aesthetic delight for patrons, kings, and connoisseurs throughout the Persianate world, from Anatolia to South Asia. The end result was the creation of a style equally attractive for calligraphers crafting the looping letters and diamond-shaped diacritics of the delicately curved script as it was for the connoisseurs left in awe of its artistry.

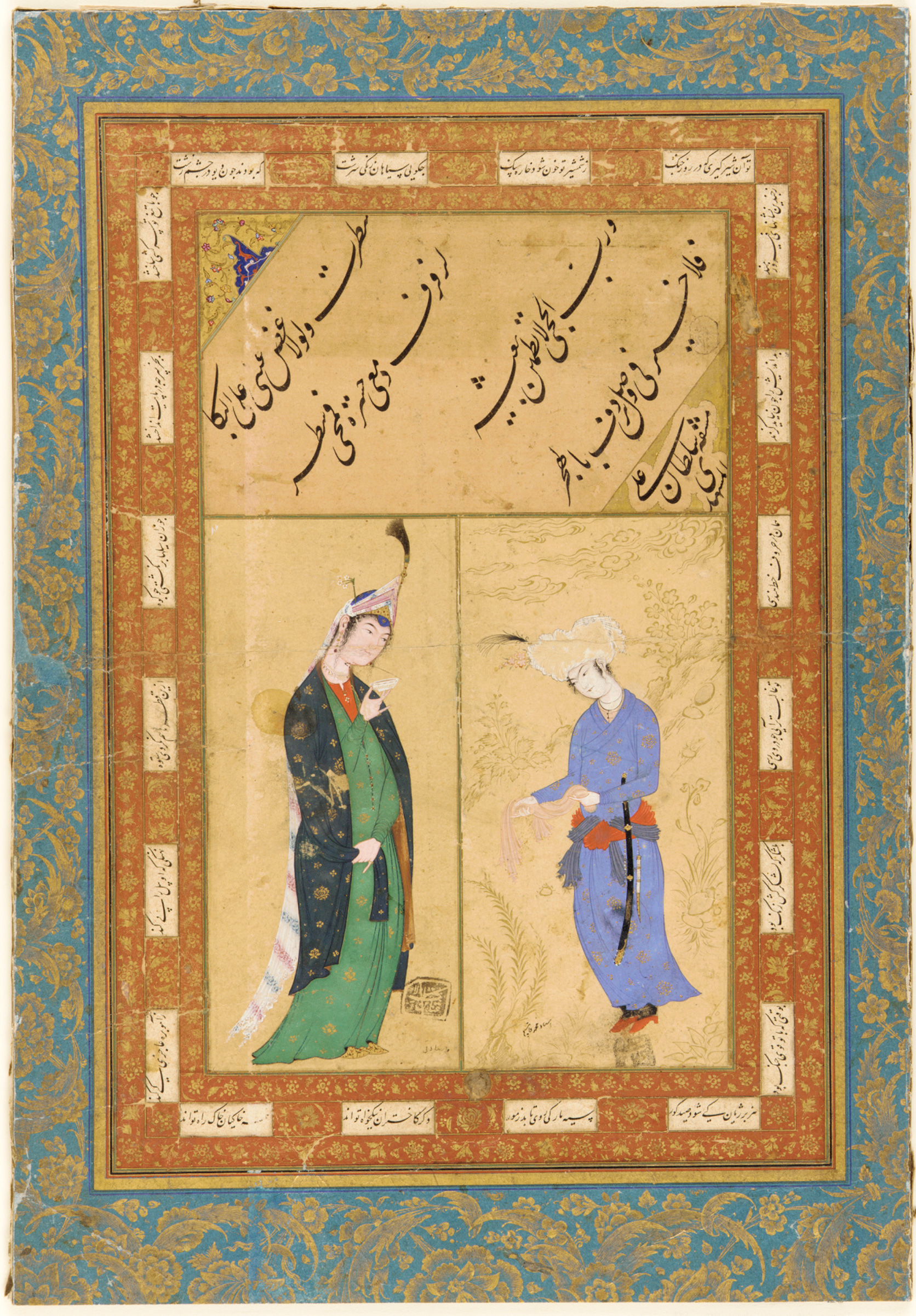

A folio featuring the calligraphy of Sultan Ali Mashhadi (ca. 1510 - 1515) and the illustrations of Mohammad Sadeghi and Mohammad Ghasem (ca. 1590)

The Genius of Persian Calligraphy considers how the calligraphers honed their skills through long hours in their ateliers and raised nasta’liq to the highest reaches of aesthetic delight for patrons, kings, and connoisseurs throughout the Persianate world, from Anatolia to South Asia

The exhibition is remarkable for its ability to articulate nasta’liq’s rise to prominence in this regard by highlighting the script’s journey from its moment of inception in the workshop to its reception in the court. This process is discernible due to the nature in which many of the items on display came to be produced. When calligraphers composed pages of nasta’liq in their workshops, often favouring the transcription of lines of Persian poetry in the form of the qita’ (lit. ‘fragment’), it was hardly a certainty that such works would receive immediate consideration by a patron, or be deemed fit for exhibition. It was usually only later than a work of nasta’liq, perhaps even one consigned to the workshop floor as nothing more than a practice exercise, found life in a folio at the hands of a patron, collector, or courtier. Such discerning individuals cut out verses of nasta’liq from their original pages and appended them to separate sheets, often in different directional layouts (e.g. diagonal), and at times accompanied by newly-painted borders and miniatures. As such composite pieces were usually pieced together at different times and places from the scripts’ points of origin, newly-configured products started to emerge, at once conveying the virtuosity of the calligraphers’ originals, as well as the artistic tastes of the individuals seeking to adapt the script to their own tastes or those of a patron.

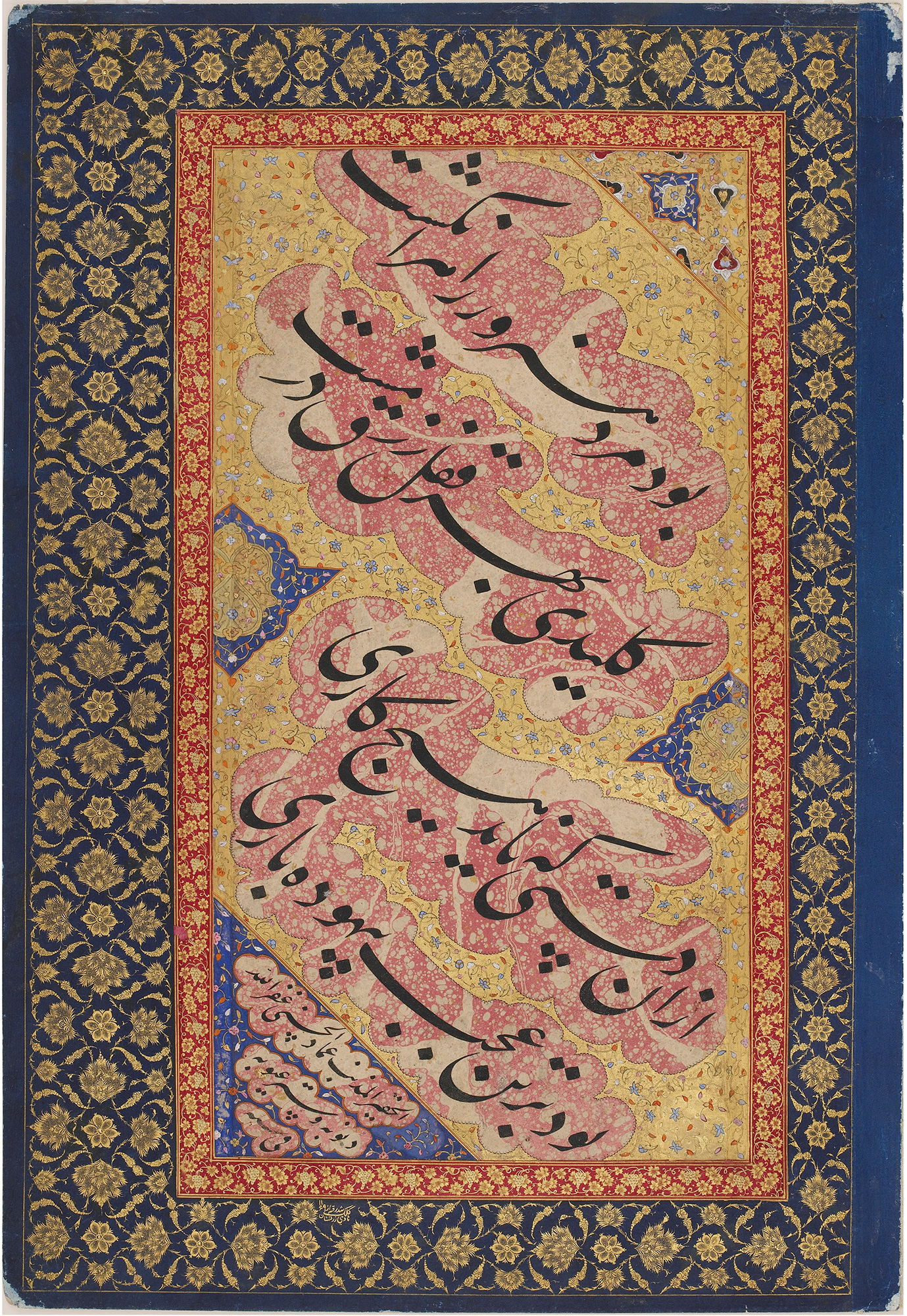

The calligraphy of Mir Emad embellished by the borders of Mohammad Hadi, produced sometime between 1611 and 1612

An exquisite display of such practices can be seen in a folio page from the famed Golshan (lit. ‘Flower Field’) album assembled for the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605 - 1627). The nasta’liq was created by Mir Ali Haravi, probably in mid-16th century Bukhara, but the borders were added in India about 50 years later, while the marginal images of various saints and the Madonna with child, based on European prints, were likely additions from when the album came to fruition during Jahangir’s reign. That the images accompanying Mir Ali’s calligraphy have hardly anything to do with the meaning of the text matters little; rather of note is the creative force of the piece in its entirety – namely the technically-astounding calligraphy itself and the manner in which it was encased – intended to leave its patron satisfied and its admirers breathless for its ability to integrate a variety of artistic mediums.

Not all creations, however, featured the style chosen by the compiler of the Golshan album and its arresting desire to enshrine examples of nasta’liq alongside a series of images. A folio page with four separate panels of nasta’liq dating from the Safavid period contains no images at all, but instead chooses to focus on the comparative techniques of several calligraphers at once. Here, the viewer is left to consider the technical precision of several closely connected, yet distinct examples of nasta’liq in juxtaposition to the more unwieldy marbled swirls of the background paper to which they were affixed. The organisation of the four panels, absent of images, presents an offering to meditate on the wonder of the nasta’liq script, and to get caught in the fluid strokes and disciplined mindset required to move from the sweeping elongation of one letter to the precise and minute upstroke of the next, and nothing more. Three of the panels are the work of Sultan Ali Mashhadi’s pupils, and the fourth likely an unsigned piece by Sultan Ali himself, underscoring what the organisers note as ‘the fundamental importance of the master-pupil relationship’ governing nasta’liq production. Like many of the items on display, the Golshan album and the four panels of Sultan Ali and his students elucidate the styles of master calligraphers as much as they do the afterlives of their works for a range of admirers in locales throughout the Persianate world. This serves as yet another reminder of the shared practices of artistic production and the deeper cultural attitudes of consumption that bound together a wide range of peoples.

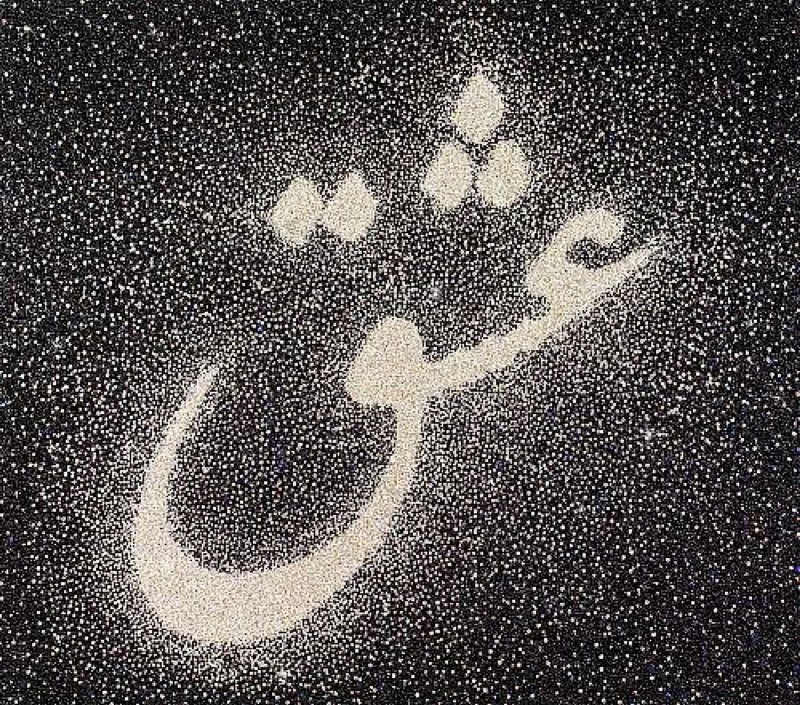

Farhad Moshiri - Eshgh (Love); Courtesy Galerie Perrotin

The allure of nasta’liq far exceeds the period of its germination in the early modern era, having attracted various artists through the ages, not least of all contemporary ones seeking to incorporate the traditional nature of the script into larger commentaries on the exigencies of the modern world. Across a variety of mediums, Iranian-born artists such as Parviz Tanavoli, Farhad Moshiri, and Alireza Astaneh have capitalised on the attributes of the script in diverse ways, harbouring both its physical nature and association with Persian tradition to craft innovations in form and vision. Tanavoli’s iconic Heech series and Astaneh’s Verbal Cage series demonstrate how sculpture has been particularly effective in deploying nasta’liq by contorting, extending, and condensing its interlocking letters to create newfound abstractions. A piece by Moshiri entitled Eshgh (Love), on the other hand, takes the script in a different direction by constructing the word’s shiftier and fragile meaning through the careful placement of thousands of Swarovski crystals, potentially signifying in part the transcendental power and cheap commercialisation of love.

Not unlike other cultural products holding appeal across the Islamic empires of West, Central, and South Asia, and accorded a type of transregional prestige, nasta’liq is a commodity that has been produced, circulated, coveted, and displayed by and for a diverse set of peoples. It is reflecting on such realities, perhaps, that one discovers the most astounding aspect of the genius of the nasta’liq calligraphers featured in the exhibition: the ability to develop an art form attracting audiences across the world over, often recast according to local tastes, but equally valued and stirring all the same, still inspiring a generation of artists in their search for meaning in new and novel ways.

‘Nasta’liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy’ runs through March 15, 2015 at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

Cover image: Alireza Astaneh