Tales of hope and hopelessness from Morocco to Iraq and beyond

A sooty, white automobile gently swerves to the side of a dusty road near a nondescript Moroccan town. Inside the stifling contraption, reeking of stale cigarette smoke and acrid sweat, can be heard the muffled voice of a Berber belle and the twang of a battered steel string guitar. The car comes to a subtle halt, and from within emerges a cloaked figure with a gaze suspended between despondency and apprehension. After surveying the boundless expanse ahead, daubed in soft yellows and greys with splotches of white through squinted eyes, he austerely makes for the town with a pungent leather duffel bag clenched between his tobacco-stained fingers. Were it not for the conspicuous North African setting and the sweet sounds of Tamazight verse, the scene could have passed for an episode out of Kerouac. It is not, however, the spirit of the free-spirited American iconoclast that lurks beneath the shadows of the whitewashed walls here, but rather of another man of letters, whose presence is marked, yet ever subtle.

Inspired by the writings of the German intellectual Walter Benjamin, Moroccan-Iraqi director Tala Hadid’s The Narrow Frame of Midnight represents a six-year long artistic effort brought to fruition through a hectic casting process and a struggle for funding, among other obstacles. The title of the film refers to a passage from Benjamin’s The Origin of German Tragic Drama, which contains some reflections of his on the subject:

There is a good reason for associating the dramatic action with night, especially midnight. It lies in the widespread notion that at this hour time stands still like the tongue of a scale. Now since fate, itself the true order of eternal recurrence, can only be called temporal in an unauthentic, that is parasitical sense, its manifestations seek out time-space. They stand in the narrow frame of midnight, an opening in the passage of time, in which the same ghostly image constantly reappears.

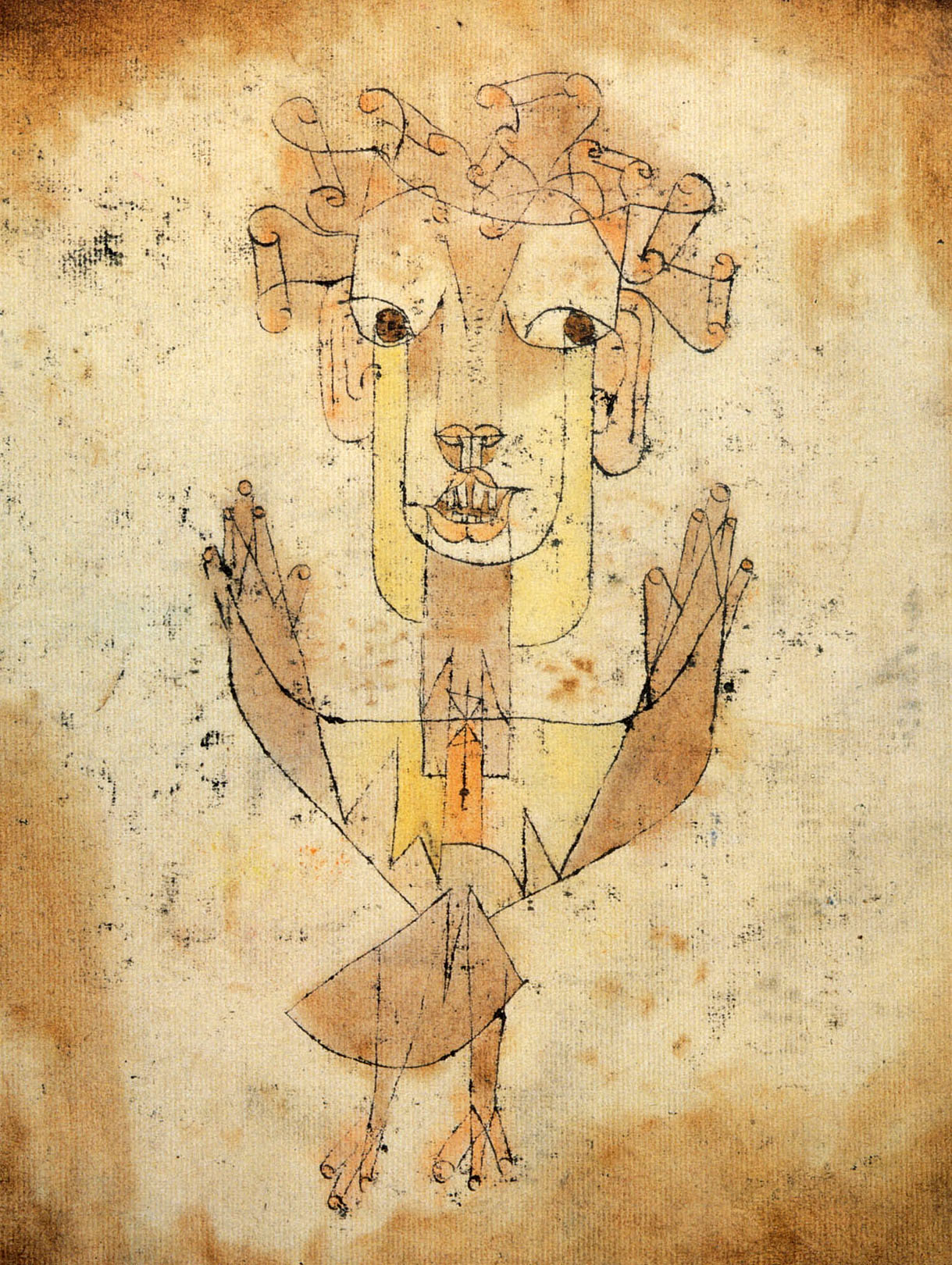

Paul Klee - Angelus Novus

That being said, though, Hadid’s film revolves not around this concept, but rather another of Benjamin’s, this time regarding history as opposed to drama. In reflecting on history, Benjamin once referred to a painting by the Swiss-German artist Paul Klee – entitled Angelus Novus (New Angel) – which he termed ‘the angel of history’. The painting features a figure bearing more similarities to the startling creatures in Qazvini’s 13th century manuscript The Wonders of Creation and the Oddities of Existence and Esfahani’s similar 14th century Book of Wonders than an angel. It stands looking rightwards with its arms raised, as if intending to provide some sort of sign or warning. To quote Benjamin,

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

At the outset, the references to Benjamin are rather scant, and Benjamin’s angel has yet to take flight; it is rather towards the end of the film that Hadid beautifully manages to tie in these concepts and references. Beginning in the aforementioned nondescript Moroccan town, the film follows Zakaria, a Moroccan-Iraqi writer who has come from abroad in search of his brother, an ex-Marxist who dabbled with a dangerous concoction of religion and politics. Along the way, his journey becomes intertwined with those of a motley crew of characters, including a sensitive Moroccan prostitute (brought to life in a cameo by Moroccan-French songstress Hindi Zahra, who provided the sounds for the film’s opening scene), an Algerian thug and his battered and bruised ‘girlfriend’, and little Aicha. Zakaria takes pity on Aicha, who begs him to save her from the clutches of Abbas the thug and his consort, Nadia, who have planned to sell the girl into a life of prostitution in France for a handsome reward. Leaving her at the idyllic countryside getaway of his French lover, Judith, Zakaria’s search takes him to an almost post-apocalyptic Baghdad via a squalid Istanbul and a picturesque-yet-foreboding Turkish Kurdistan.

Khalid Abdalla and Hindi Zahra

Where we perceive a chain of events, [the angel of history] sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise …

Though on the surface the film’s leading characters may seem worlds apart, they are united by their hope and their desire for freedom. Zakaria, feeling a sense of guilt and shame for not having been there for his brother when he was first imprisoned, seeks release in finding him. Aicha, on the other hand, simply yearns to frolic in the wild, verdant plains of Ifrane like other children her age, and enjoy the warmth and love of a mother she never had. Their hope spurs the two characters forth on two very different journeys, with two very different outcomes; while Aisha manages to find that which she sought, Zakaria only finds death, destruction, and utter hopelessness: the face of present-day Iraq. Like Benjamin’s angel, he strives to reverse the irreversible, albeit to no avail. The words of a man he meets in Baghdad whilst searching for his brother are the only ones that bring a smidge of consolation to both him and the viewer, perhaps:

They say that when the Mongols invaded Baghdad, they burned all the libraries, destroying thousands of years of history in an instant. The rivers ran black with ink; now, they run red with blood. Iraq will rise … we will have our time again.

With such a compelling plot and storyline, and considering the tastefully-peppered dialogue, it is easy, in discussing such a film, to overlook its more atmospheric and ambient aspects. Watching The Narrow Frame of Midnight, one recalls the cinematic landscapes of contemporary Turkish films such as Semih Kaplanoğlu’s Bal, Reha Erdem’s Hayat Var, and Zeki Demirkubuz’s Masumiyet, wherein emotions, moods, and imagery are given paramount attention. The desolate city environs of Morocco foreshadow, in a way, the unsavoury events yet to occur in the story, as well as reflect the mood of the characters; in Ifrane, one can almost, along with Aicha, feel the breeze of the sweet countryside air, and sense the soft blades of wild grass between their fingers; the grandeur of Istanbul’s Ottoman relics, contrasted with the city’s sordid side streets and the alien sound of Turkish confirm a feeling of strangeness, while the bleakness of Baghdad stinks of the sickly sweet smell of death.

Above all, Hadid’s film is one that urges contemplation, and through the director’s cinematic approach, viewers are provided ample opportunity to reflect on, and engage with the panoply of emotions sumptuously and evocatively portrayed on screen. Perhaps most moving are the film’s final scenes that take place within and outside a Baghdad morgue, which Zakaria visits in the faint hope of at least being able to identify his brother’s corpse, should it be there. Aside from the washing of blood, the echoes of footsteps, and intermittent recitations of the Koran, nothing else is to be heard. On the floor of the morgue, corpses lie scattered under pink sheets; the chilling bird’s-eye-view shot of the scene helps one realise, to a small degree, the number of lives claimed by the most recent Iraq war, and their concealment serves as a poignant reference to the anonymous fashion in which the victims of this war are often portrayed: that is, not as individuals, but as bodies and statistics. As he stands hopelessly outside the morgue under a relentless sun, his coarse linen shirt soaked to the core, an incessant throng of black, shapeless figures brush past him, eerily evoking the imagery and feel of Shirin Neshat’s film, Women Without Men, as well as her Women of Allah series of photographs. Yet again, the angel of history alights with mouth agape and wings akimbo, looking in horror at the past: The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.

It is perhaps such scenes that remind one that Hadid’s film is not only about the stories of various characters, each on a journey of their own, but also about Iraq. Indeed, the final ‘chapter’ of Hadid’s film is not easy to digest – both visually and emotionally – as it highlights the gruesome consequences of the Iraq war and the miserable fate of the Iraqi people in vivid, brutal colour. While there’s certainly much more Hadid has to say about Iraq and the atrocities that have been, and are continuing to be committed there, she feels that for the purposes of the film, enough has been said and left open for discussion. ‘If I wanted, I could have made a 15-hour documentary about Iraq, but that’s not what I intended to do’, she remarked after the film’s screening at the Toronto International Film Festival in response to a perturbed viewer who complained about there being no mention of American involvement in Iraq in the film. Ultimately, through Zakaria – that wingless angel – Hadid sublimely tells a lush story of hope and hopelessness, scaling down and imparting the horror of modern Iraq on a human level. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise …