Shifting perspectives through Arab pop culture ephemera in London

Although far from being homogenous – a fact well-known to readers of this publication – the ‘Middle East’ is still viewed as such, with alternative notions having yet to trickle into the general consciousness of the masses outside the region. Neo-Orientalism still continues to dominate Western discourses around the diverse cultures constituting the Middle East and North Africa and their relations with one another, while the Arab world is portrayed as a monolith, ever plagued by civil wars stemming from ‘long-standing sectarian divides’ and the dehumanised peoples within.

An exhibition of Arab pop culture ephemera presented by the Arab British Centre at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London, Whose Gaze is it Anyway? endeavours to turn such tropes on their heads. The small, yet poignant show staged as part of the ongoing Safar: Festival of Popular Arab Cinema at the ICA, is predominantly made up of vintage film posters and photographs belonging to the prominent Lebanese collector Abboudi Bou Jaoudeh in Beirut. The exhibition represents the first time many of these artefacts have been shown in the UK, and in some cases, outside of Beirut altogether.

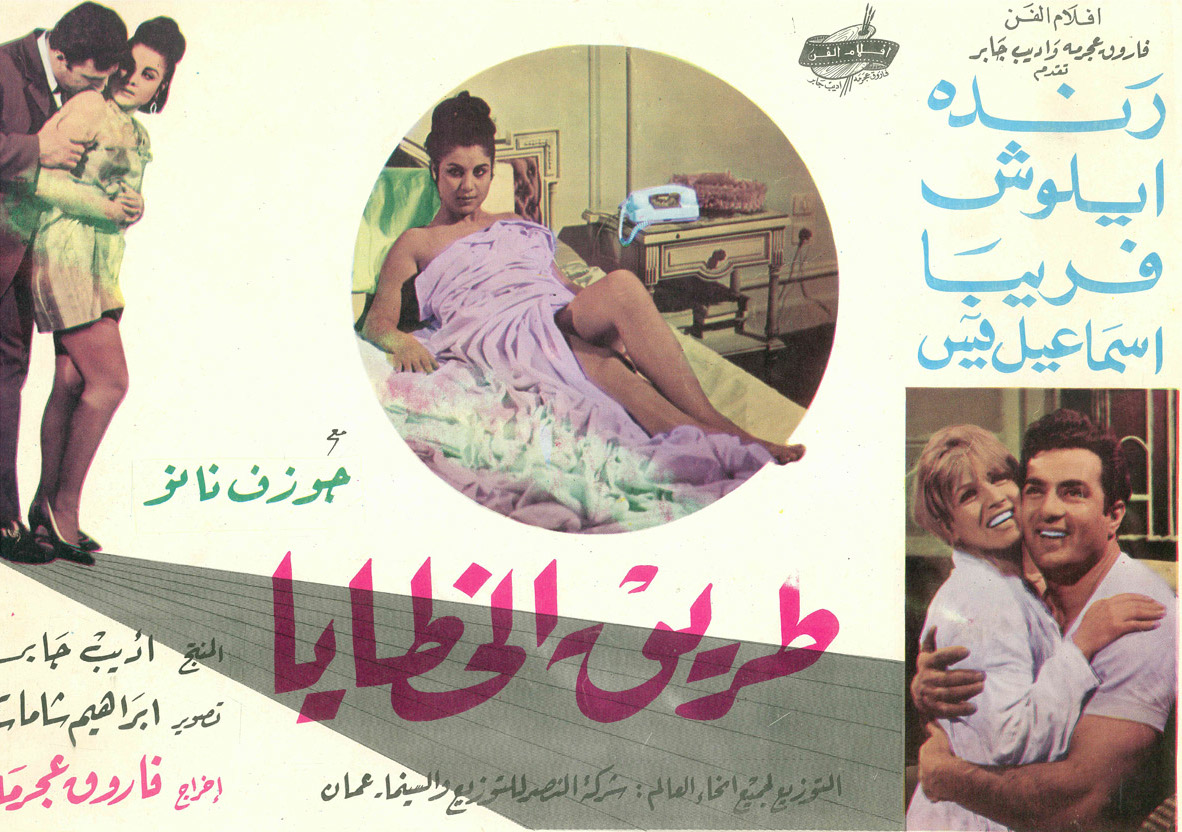

To Western eyes, the posters look incredibly familiar, evoking Hollywood themes, and belonging to the romance, horror, and thriller genres. As well, many of the photographs feature images that are not commonly associated with Arab culture. Overtly erotic tones dominate the images, many of which feature couples embracing and an overall unabashed display of bare female skin. A promotional poster for a 1966 film, Rendez-vous à Beyrouth, shows a collage depicting a couple on the brink of making of love, a man firing a pistol, and another man seemingly defending himself. In another poster for the 1971 film Ashegh al Hayat (Lover of Life) the deed has already been done, as evinced by a couple relaxing in bed, post-coitus.

Photograph by Mark Blower (courtesy the ICA)

These similarities to Western pop culture have, however, left Arab cinema subject to its own particular brand of neo-Orientalist critiques. In his highly contentious 1973 work The Arab Mind – which in the 2000s became a prized handbook among American neo-conservatives studying torture methods for use in the infamous Abu Ghraib and other prisons – Raphael Patai wrote that Middle Eastern film is symptomatic of a wider desire in the Arab world to assimilate Western culture. Because of this, he and other critics have claimed that Arab cinema represents a deplorable mimicry devoid of authenticity, and therefore also of the credibility afforded to Western films. As he wrote,

Most teachers at [Arab art schools] consider the traditional arts and music backward and primitive, and instil into their students a hostility toward them, and contempt. Add to this the impact of Western magazines, books, films, radio, and television programmes, exhibitions of the works of Western artists, and concerts given by Western musicians and orchestras, and you have an atmosphere suffused with the simplistic dichotomy which holds that Western art and music equals good, while traditional Arab art and music equals bad.

For Patai, the similarities to Hollywood that Arab cinema displays is not a sign of some cultural equivalence, but instead the result of a unilateral cultural ‘import’ into the Arab film industry that only serves to further accentuate its ‘otherness’.

A poster for the 1968 film Tariq Al Khataya (Way to Hell); courtesy the collection of Abboudi Bou Jaoudeh

Alternatively, in her 1996 book Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity, Viola Shafik countered Patai’s assumption (also espoused by many others), stating that ‘the idea of cinema as an alien cultural element, implanted in a quasi-virgin Arab culture, has to be questioned in the same way as the notion of cultural “authenticity”’. According to Shafik, ‘Authenticity can only exist within an impermeable cultural environment, cut off from foreign influences’. This, as the author posited, was far from the case in the context of Arab cinema. ‘The countries of North Africa and the Middle East have never formed a closed and secluded cultural environment’, she noted, adding that ‘The popular cultures as well as the high cultures of these countries serve as evidence of this’.

In presenting the complex tapestry of Arab cinema’s colourful history – complete with imagery countering predominant discourses on Middle Eastern culture – Whose Gaze is it Anyway? provides a subtle but direct challenge to worrying perspectives

Films made in Egypt have long dominated the Arab film industry. Egypt was the first Arab country to take advantage of sound innovations in the beginning of the 20th century by promoting Egyptian songs and singers who proved to be commercial successes across the Arabic-speaking world. Early Egyptian films tended to fit snugly into one of four popular genres: musical, melodrama, comedy, and adventure. Such films were also characterised by a series of comic episodes, 1,001 Nights-style fantastical tales, or unlucky love stories.

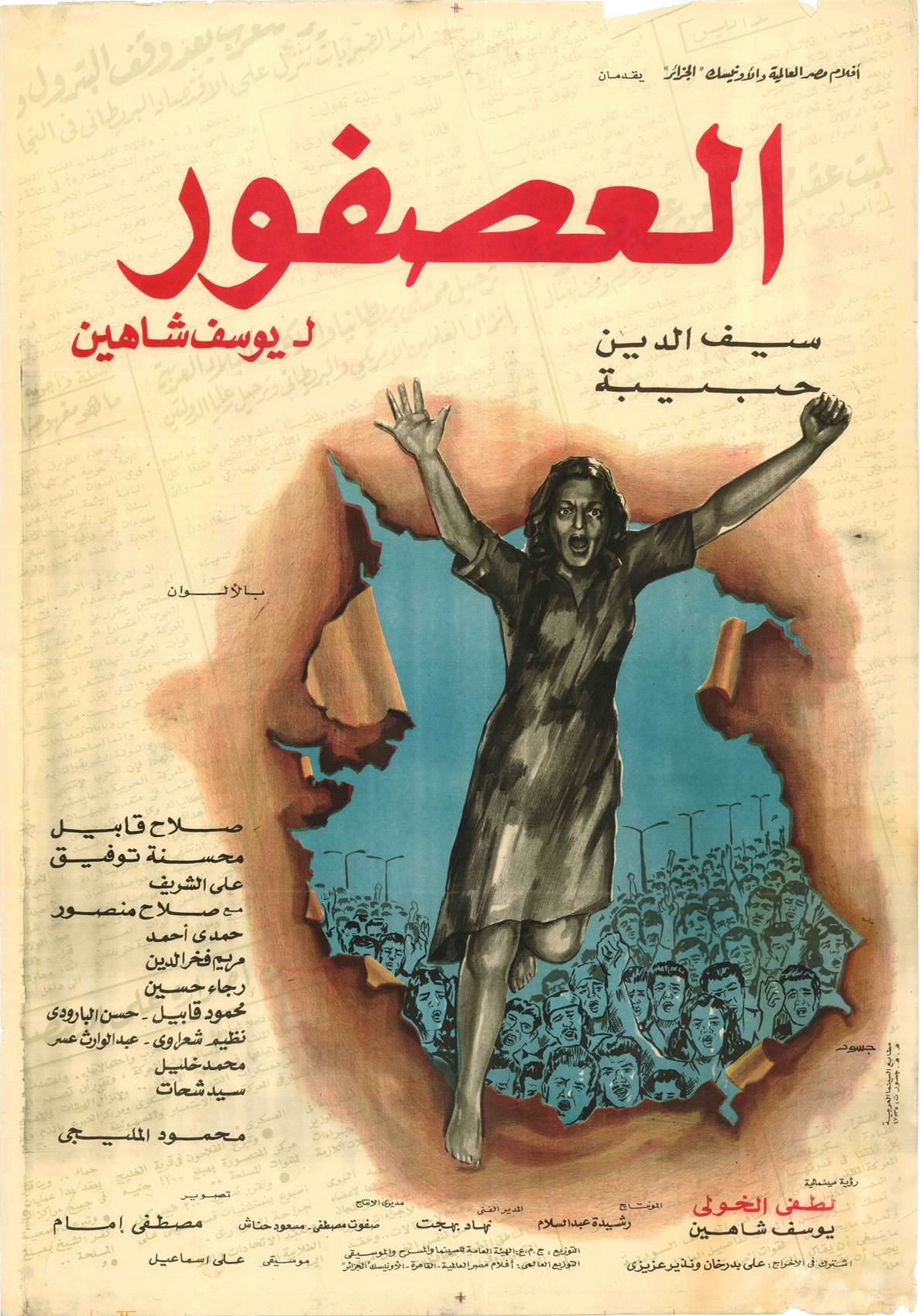

A poster for the 1972 film Al Asfour (The Sparrow); photo by Mark Blower

In the years following the Second World War, with an end to import restrictions that had hitherto been in place, Egyptian cinema developed genres that presented a complex mix of the above themes in addition to ones adapted from Hollywood; as a result, the signature melodramatic realism that has become synonymous with contemporary Arab cinema was born. As with Bollywood films, however, dance interludes – particularly traditional dances – remained integral to Arab films. This post-war period during the reign of the revered Gamal Abdel Nasser is still widely regarded as the ‘golden age’ of Egypt’s cinematic history. It was during this era that Egypt’s film industry developed upon its already strong pan-Arabian commercial foothold, with steady advertising spots and the rise of larger-than-life starlets such as Soad Hosny. The commercial aspect of the films produced during the period was so strong that even the brief period of nationalism under Nasser couldn’t fully assuage it. There were, however, a number of ‘art’ films that sought to develop a cinematic language indigenous to Egypt, such as Shadi Abdel Salam’s seminal 1969 classic, Al Momia (The Night of Counting the Years).

It is this strong history of commercialism – as well as populism – that is celebrated in the exhibition’s posters, alongside the idea of an Arab culture that has successfully been sold to itself, as in the case of Hollywood. This notion contrasts beautifully with Maha Maamoun’s 2009 film, Domestic Tourism, which plays in a corner of the exhibition. Maamoun’s work is a montage of historic film sequences featuring the Giza Pyramids in the background. These films one acted as a form of product placement for the tourism industry, hence the title of the work. The film attempts to highlight how both Egyptian cinema and the cultural landmarks have been used by the tourist industry over the years, as well as to engage with cinema’s shared history with both propaganda and advertisements. In the tourism industry – perhaps more overtly than in any other – nationalism and commercialism coexist. For Maamoun, the Pyramids are national symbols for a flourishing, modern country, as well as a means of encouraging travel.

Photograph by Mark Blower (courtesy the ICA)

As the exhibition’s curator, Omar Kholeif, once mentioned, one of his key aims was to explore how such a ‘gaze’ came to be constructed in the Arab world through the medium of film, as well as – in his own words – ‘how these [works] will be viewed by a largely Western audience’. This is perhaps more pertinent now than ever before, as this show has, by happenstance, coincided with yet another foreign attack on Iraq. The steady, highly-publicised rise of ISIS, largely framed in neo-Orientalist rhetoric and imagery, is further adding to the notion of a homogeneous Arab ‘other’, as well as other cultural malaises. Although relatively small in size, in presenting the complex tapestry of Arab cinema’s colourful history – complete with imagery countering predominant discourses on Middle Eastern culture – Whose Gaze is it Anyway? provides a subtle but direct challenge to worrying perspectives.

‘Whose Gaze is it Anyway?’ runs through October 5, 2014 at the ICA in London, as part of the Safar: Festival of Popular Arab Cinema, which runs through September 25, 2014 at the ICA.