Challenging stereotypes in NYC’s first museum exhibition dedicated to contemporary Arab art

‘Oh, father of straight talk, your words are a cure’, purrs the jazzy blonde chanteuse in Adel Abidin’s video installation, Three Love Songs. Working the microphone for her nightclub audience, she sings in clipped Iraqi-accented Arabic a melody Western and familiar, with lyrics troubling in translation; yet, these are no ordinary love songs: each piece was commissioned by Saddam Hussein during his decades-long reign to glorify his rule in Iraq. Through Abidin’s clever and unsettling stylisations of lounge, pop, and jazz genres, the audience comes to understand the importance of seduction when wielding absolute power.

Topics such as terror, regimental rule, Western influences, and Arab identity are all vastly explored in Here and Elsewhere, an exhibit of contemporary art ‘from and about the Arab world’ (in addition to works by Dubai-based Iranian artist duo Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh) on view at the New Museum in New York. Taking its name from a 1976 film-essay by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville – that focused on the ethics of representation and responsibility in the face of political consciousness, and which used footage from Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s 1970 PLO-sponsored film, Until Victory – Here and Elsewhere is a complex banner that raises questions about the idea of a collective Arab identity as working artists encounter a constantly changing landscape. Such a feat may have otherwise proven problematic for many Western curators and institutions, as the Arab world is far too vast to single out an agreed-upon ‘Arab’ representation of art; yet, the New Museum has challenged itself to create an ongoing dialogue that engages viewers to tackle preconceived notions of an oppressive and culturally stagnant region.

Massimiliano Gioni, the museum’s Artistic Director has been championing the work that lives beyond the confines of the New York art world, eager for audiences to encounter fresh and unfamiliar aesthetics – an endeavour that began with 2011’s Ostalgia, which showcased works from Russia and the former Soviet Union. Enormous in scope, and spread out over all five floors of the museum – including the lobby, where a photograph of a flashy hotel in an oil-rich Persian Gulf state spreads itself above the ticket counter – Here and Elsewhere is comprised of the works of over 45 new and established artists from 12 countries, some of which are being shown for the first time in New York City. The exhibition is more significant than the sum of its parts, however, as it represents the city’s first museum exhibition dedicated to contemporary art from the Arab world. As it clearly shows, Arab art is no longer confined to biennials and art fairs around the world; this long-overdue exhibition has all the trappings of a well-informed debut, and comes at a time when the Arab world has the potential to be viewed in a more vibrant – yet no less serious – light.

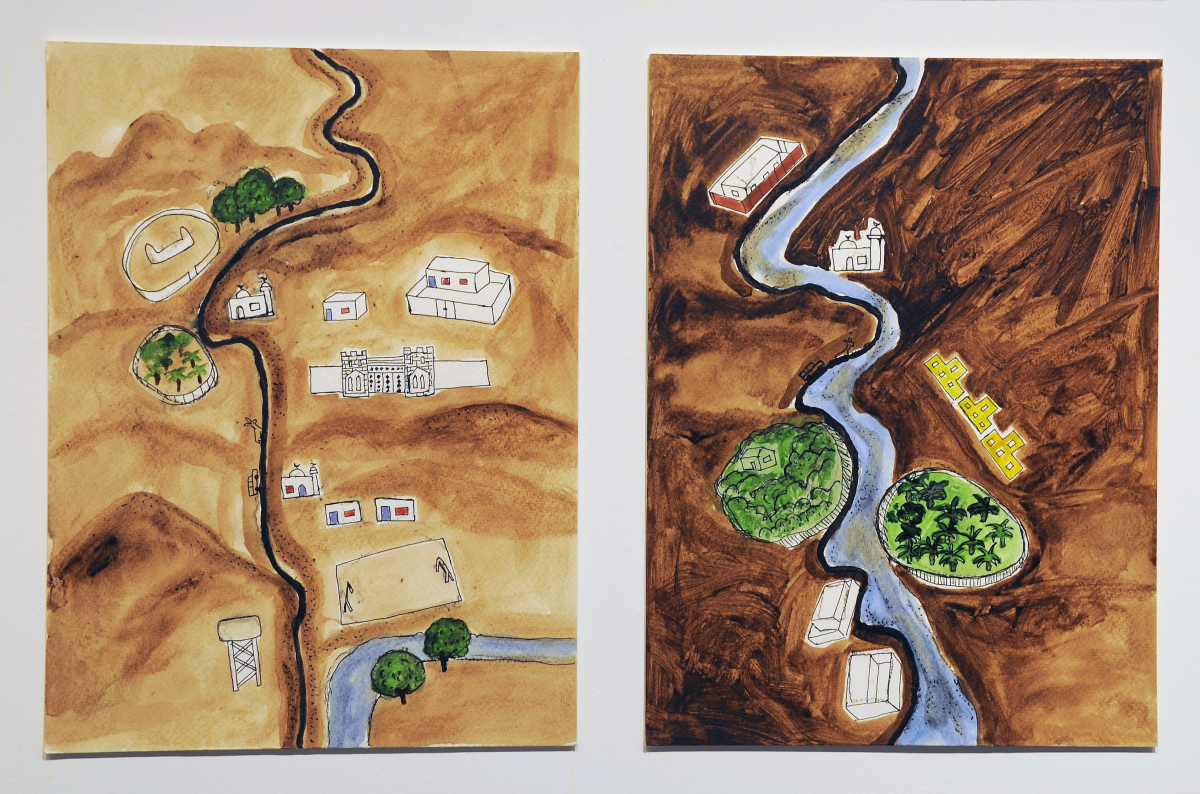

Abdullah Al Saadi - Camar Cande’s Journey (courtesy the Sharjah Art Foundation)

With the recent (albeit constant) political turmoil threatening the already sensitive region, history presents a complex and bloody terrain for these artists to draw inspiration from, and no topic – from private identities in a photographer’s studio to tracing a refugee’s journey from Europe to Mecca that dismantles itself into a holy amusement park – is too ‘heavy’ or too inclusive for the artists. One of the first works encountered in the show is Abdullah Al Saadi’s Camar Cande’s Journey, which presents a series of almost childlike maps drawn during a 20-day trek through the northern Emirates and Oman the artist completed whilst accompanied by a dog and a donkey named Camar Cande (perhaps a reference to the arduousness of the voyage, with ‘Camar Cande’ literally meaning ‘stripped/broken back’ in Persian). The maps read journalistically, almost like an On the Road of sorts, with charming markings, as if Al Saadi were explaining directions to a friend’s house – such is the intimacy of his lines. Like any encounter with maps of the Arab world, one has to recognise and respect how ancient the lands therein are, despite the modern conflicts that so desperately try to shape and change them. This encounter is made all the more apparent when coupled with the mixed media work of Hassan Sharif’s hanging objects, which include a horrific and colourful giant jellyfish comprised of plastic bits and ends, as well as boxed items, ropes and shoes, and plastic and paper, that come together like an endless bazaar of banality for the tireless modern consumer.

Still from Bouchra Khalili’s ‘Mapping Journey Project’

This long-overdue exhibition has all the trappings of a well-informed debut, and comes at a time when the Arab world has the potential to be viewed in a more vibrant – yet no less serious – light

Journeys are a constant theme throughout the exhibition, and become a familiar tool to guide audiences through difficult periods in nations’ histories – such as the Lebanese Civil War, the Gaza crisis, and the Iraq War – with mixed media, photography, painting, and digital works expressing what the news and media cannot: the deeply personal relationship of an artist with their surroundings; but what many of the works convey, in one room after another, is a sense of grace and duty that encompasses the responsibility of the artist to act as a speaker of truth. In Bouchra Khalili’s Mapping Journey, one regards the hands of migrants and refugees who crossed the Mediterranean from Africa and South Asia trace their complicated routes from start to finish with felt pens on store-bought maps. Unwavering voices weave stark and moving narratives in telling the details of being stranded at sea, experiencing crippling heat, and having to leave families behind. Anna Boghiguian’s artist journal, on the other hand, reads like a wordless graphic novel. Her hypnotic pen and ink drawings of Egyptian symbols and nightmarish figures give insight into the creative process endured under the continuous stress, fear, and political uncertainty of the 2011 uprising and the subsequent revolution in Cairo. Mohamed Larbi Rahali, a Moroccan artist who preferred working as a boat mechanic until beginning a series of doodles on discarded matchboxes in 1984 has assembled thousands of such works created since then, which he has presented in Omri (My Life). Such are some of the distinctive and anxious oeuvres of many of these artists, who create narratives lacking the normal pretensions so otherwise prevalent in contemporary art.

Fouad Elkoury - Untitled (courtesy The Third Line and Galerie Tanit)

Arresting and beautiful, the black-and-white photographs of portraitist Hashem El Madani (who opened his studio in 1947) show a pre-Civil War Lebanon of schoolgirls with ribbons and same-sex couples sharing more personal moments, thanks to the conservative norms of the day that otherwise prohibited men and women from kissing on camera. The images take a turn, however, with grinning youths in trendy bellbottoms posing with automatic weapons for the camera further down in the gallery. The years predate the crisis in Lebanon by a hair; such were the clairvoyant qualities of El Madani’s lens. Similarly, Fouad Elkoury’s photographs of sunbathers at a country club and families posing amidst the rubble of Beirut – a tourist’s snapshot of horror – document the years before and after the devastating 15-year long Lebanese Civil War.

And yet, some journeys do not take place as planned, or at all, such as the real-life case of Palestinian artist Khaled Jarrar, who was prohibited from leaving the West Bank to attend the exhibition’s opening and participate in a public artists’ panel with Lamia Joreige and Charif Kiwan. The irony of life imitating art cannot be clearer in regarding his works; the film installation Infiltrators, for example, conveys the harrowing distress of Palestinians trying to leave disputed territory by repeatedly striving to scale the wall that divides them from neighbouring Israel.

Objects of conflict and warfare do not necessarily represent themselves in the form of weapons, however; Wafa Hourani’s vast Qalandia imagines the complicated utopia of a Palestinian refugee camp (Qalandia being a violent and contested checkpoint between Ramallah and Jerusalem), where Arabic pop, disco balls, and Christmas lights make up the box-like structures on the tables in the middle of the gallery. A video installation by Lamia Joreige portrays 11 survivors of the Lebanese Civil War who speak about their experiences through various objects – a teddy bear, a driver’s licence, a candle, a broken tape player, a suitcase – that reveal the complexity of multiple characters attempting to piece together a conflict. This is something that each artist participating in the exhibition recognises: there is no absolute truth, no singular narrative that holds the rationale or great revelation to any moment in the histories of these countries that can suffice for audiences, and perhaps this is the point. Rather than pinning down an adjective, viewers are left with the feeling of how enormous and multifaceted the Arab world is, and how crucial the practices of artists are, who live and work to tell the ongoing stories therein, rather than allowing the media and the outside world to write their final chapters and confine them to lines on a map.

‘Here and Elsewhere’ runs through September 28, 2014 at the New Museum in New York City.