Palestinian artist Khaled Hourani speaks about his first-ever retrospective

Translated from Arabic by the author

Among his many achievements and his status as one of Palestine’s most important and relevant contemporary artists, Khaled Hourani is probably best known for his role as a co-founder of the International Academy of Art in Palestine, and for bringing - for the first time - a work by Picasso into the West Bank in 2011. This year marks another first for the artist, whose works from 2000 to the present are currently being displayed at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts in his first-ever retrospective. REORIENT’s Inaya Hodeib caught up with Khaled to chat about the works being exhibited, his artistic practice, the phenomenon of idolatry, and - among, of course, other things - cats.

You are known as an artist, a curator, and an art critic – what led you to take such paths? Did the decision to become, for instance, a curator come to you naturally, or were you in a situation where you felt change was needed?

What matters to me is the practice of art. We live in countries where an artist is forced to play more than one role at the same time – writing, organising shows, and even producing them, among many other things. I can say that I find a lot of good comes from all this, since nowadays all these [activities] are linked and are very important aspects of contemporary art; the lines are utterly blurred between curating a show, producing one, and even writing.

I have often found myself working in these fields more than once – not only through organising art exhibitions like the Picasso in Palestine project that took place in Palestine, and which [was] a very good example of how an artist can himself be involved in the process of curating – but also because more than once the nature of what needed to be done in order to convey a message or idea that I wanted to share with others simply required me to write about the matter, or produce a whole show with several art works; and in most cases, my works were not among them. In such cases, I do not care what the ‘process’ itself is called, be it art, curating, or writing.

Among these three practices – curating, creating art, and art criticism – is there one you feel you identify with the most, or would you say they are all somehow interrelated?

I prefer being an artist, because at the moment [creating art] is what I do best; but, I do consider that writing and research are very vital processes of the artistic practice as a whole, since every project has different requirements. I love and am passionate about being a participant in art and exchanging ideas and dialogues with everyone, and in the end … as I said - the most important thing to me is the artistic process, and sometimes that means thinking outside the box and embracing all [of art’s] aspects.

A still from Picasso in Palestine

What are your thoughts about the retrospective at the CCA? Are there any works you’re more connected with than others? And, is there anything you would have liked to seen on display that isn’t?

I consider this show to be a great opportunity to look back at everything that has happened, and a chance to ‘reorganise’ myself. I have done many projects – some have been very successful, while others less [so], and some even totally forgotten. [For] this exhibition, I went back to everything I had worked on from different [points in] my career. It was helpful, as I had a chance to reflect, learn, compare, and see what projects I could [work on] in the future … and as you already know, there is only one new [work] in the exhibition, and [it] is about [2013 Palestinian Arab Idol winner] Mohammad Assaf. The work is about the phenomenon of being a star and an idol, and about the symbols and beacons that people look for in times of great distress.

There are of course many other [works] I could not present in this retrospective, since I had to pick my favourites [from among all my works] with the help of the organisers and curators, [and] also because I wanted to focus and highlight the one project that I found to be the most important during the past 25 years.

We once had a wonderful chat about the subject and focus of your latest paintings – your cat Assal (Honey). Is he featured in this retrospective?

Yes, Assal is featured in the show, and I made sure that I borrowed the painting from its current owner in Ramallah, since it is a metaphor [of] going back to one’s true self and the search for the simple and [the] normal – especially since I made this work at a time when I was busy with very big and exhausting projects. I painted it because I was looking for peace and quiet, and I was meditating [on] everything around me. [He] is a beautiful cat, and … a very close friend to me … I truly love him.

The Road to Jerusalem

The retrospective at the CCA includes many works made since 2000. However, the statues of Mohammad Assaf seem to be receiving lots of positive attention. Why did you pick him in particular to ‘immortalise’?

A hundred sculptures of the beloved Assaf [represent] my only new project in this show. I have dedicated a special space for him in the exhibition, and even the poster for the retrospective is [of] one of the sculptures. The Mohammad Assaf phenomenon represents a new landmark in the lives of Palestinians and Arabs, and perhaps this [is what] grabbed my attention, [especially] since we live in such a time of struggle and continuous turmoil in the region. On a personal level, I was very happy to see such a young man gaining this much success and love, ‘beating’ all traditional political parties and leaderships, even though he was only singing; this phenomenon surpassed the simple acts of voting and competing and winning … it somehow shed a very big spotlight on politics, and revealed a weakness in there of some sort. It also showed how much the Palestinian people needed an idol, and spoke of their desire to find a new hero; only this time, the hero was [one] of them – especially the young who are deprived of any opportunities – not to mention the fact that his voice and performances were beautiful.

People in Palestine need art in order to find creative ways of dealing with situations that can be very tough and sometimes even impossible. We have a very vibrant and active art [scene] in Palestine, which is something that speaks positively about the future; but the [usual] image [of Palestinians known to] the world [is of] victims or ultimate heroes – something I do not like

Where will we take this idol? Where shall it lead us? I have no clue. In this project, I try to analyse the phenomenon – not the person – because for me, personally, I really liked this young man, and I even voted for him like everyone else … so, I wanted to [look at] the [subject] from a new perspective – for as much as I was happy and thrilled when he won, the thought of how much he meant for everyone as an idol scared me.

Is there anything in particular you would like your audiences to take notice of in this retrospective? Are there any messages – personal, artistic, and/or political – you wish to convey?

Nothing in particular; I only hope that every visitor takes his or her time [to see] all the works exhibited, and to take notice of the stories surrounding each work, since all the projects are not independent or abstract – they all have tales behind them, and I truly enjoy storytelling.

Which works in the retrospective do you find tell of the happiest and hardest moments, both in your personal and professional life?

I am especially fond of the Kadima (Hebrew for ‘Forward’) project, which I made [on a] zero budget; I created it after reading an article in a newspaper. The project was basically a Palestinian version of the Israeli Kadima party; what I did was use the same programme and agenda of the Israeli party, only changing the words ‘Palestine’ and ‘Palestinians’ to ‘Israel’ and ‘Israelis’ and republishing the article in the daily Palestinian newspaper Al Ayyam. I was able to create a very simple project that was extremely relevant to our time. I [am also fond of] the Picasso in Palestine project, which took an enormous amount of time – years, in fact – of being anxious and nervous, [and cost] around a quarter of a million dollars.

What is it like working as an artist in Palestine today? Are there any particular difficulties you encounter?

Being an artist in any part of the world is a very relevant thing, and there are certain circumstances for each country, time, and place. Palestine has witnessed the worst of cruelty that cannot be hidden from anyone; it is a story of a long struggle where everything has become familiar. People in Palestine need art in order to find creative ways of dealing with situations that can be very tough and sometimes even impossible. We have a very vibrant and active art [scene] in Palestine, which is something that speaks positively about the future; but the [usual] image [of Palestinians known to] the world [is of] victims or ultimate heroes – something I do not like. I like working in grey areas, even though the attempt to ‘break’ such an image is very hard, to the extent that it can totally imprison us – and this in itself requires a lot of effort to break [free] from.

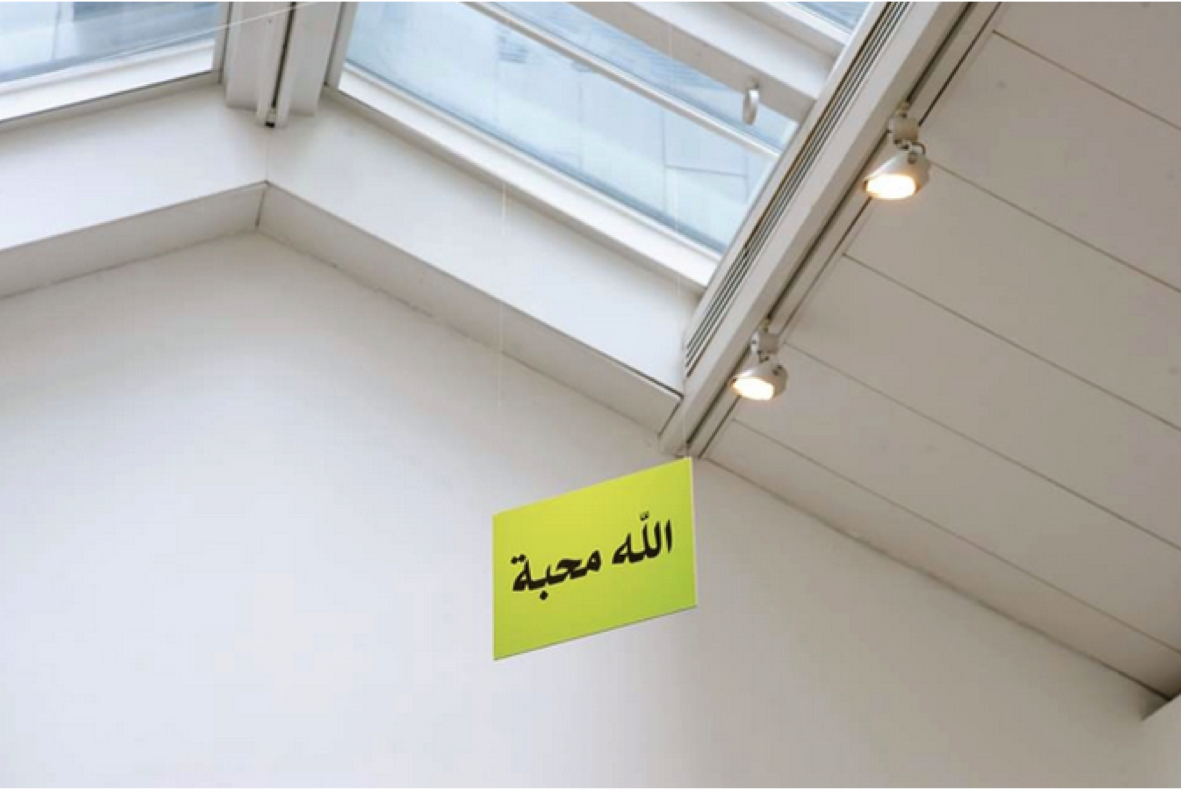

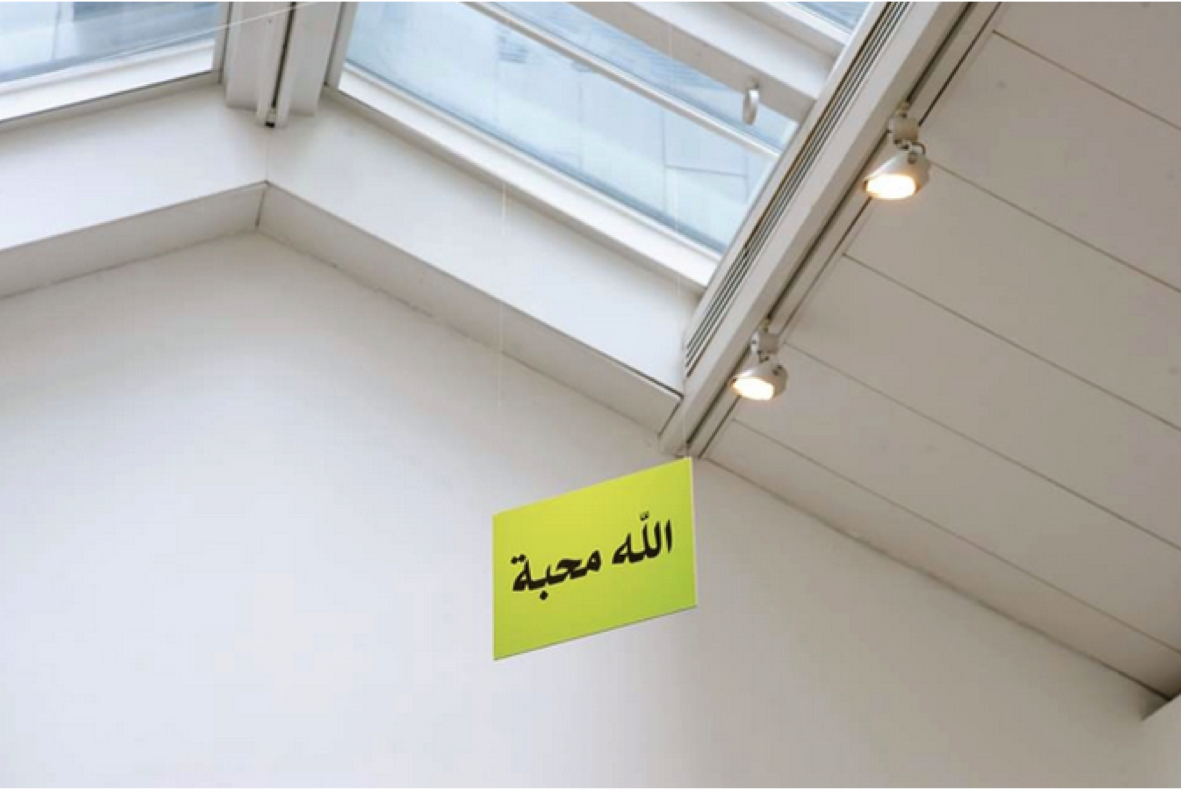

God is Love

Can you share with us a story about one of the works in the exhibition that you haven’t spoken about with anyone else yet?

Yes – the story of my work, God is Love, which I [made] in Jerusalem … the project is a collection of 28 small signs, [each] 30 x 20 cm in size, which say ‘God is Love’, [and which] I distributed all over the streets of Old Jerusalem. [This was in constrast to] the famous and popular sayings ‘thank God’ and ‘God be praised’, which are usually present in our streets. The expression got on some people’s nerves, since it refers to a religion other than Islam, [as well as] Om Kolthoum’s famous song of the same title … so, [some] removed the word ‘love’ and kept the word ‘God’, and in some cases [it was the opposite].

Khaled Hourani’s retrospective runs through May 18, 2014 at the CCA in Glasgow.