Examining the recent surge of interest in the sound of 60s & 70s Iran and Turkey

A few months ago on a lazy Sunday afternoon, as I was strolling down the quirky fashion drag that is Toronto’s Queen Street, I spotted something in the corner of my eye that seemed just ever so slightly out of context. Stopping for a moment, I looked into the display window of a trendy vinyl store, and eyed there amongst the colourful sleeves of obscure folk and rock albums the word Zendooni (Persian for ‘Prisoner’) in garish yellow lettering above a conspicuously Iranian-looking woman in a field of sunflowers; Funk, psychedelia and pop from the Iranian pre-revolution generation read the description. Lacking a record player, I immediately looked up the album on the Internet upon arriving at home (after enjoying a dose of coffee and pre-Revolution Iranian pop art at nearby R², of course), and discovered that it was yet another pressing by the American record label Light in the Attic, which had previously released albums in a similar vein such as Khana Khana!, as well as a formidable compilation of hits by the Iranian rocker Kourosh Yaghmaei and a previously unreleased selection of songs by the hitherto unknown Tehran-based garage band The Jokers.

Although I had successfully sourced with eagerness the tracks on Zendooni, it wasn’t the first time I’d gone digging in pursuit of Iranian ‘nuggets’ (as record collectors like to call them) from the 60s and 70s; that is, from that brief era of bliss before the shit hit the fan for the Iranian music industry. My love affair with these quirky disco, funk, and psychedelic tracks began some years ago during the autumn of 2009, whilst a humble university student in dankest, darkest London. Somehow or other, I managed to stumble upon a compilation of songs, mostly rarities, from pre-Revolution Iran, simply entitled Pomegranates. Featuring a wistful looking, headscarf-clad Ramesh on the sleeve, the album more or less constituted the soundtrack of my university days, and sparked within me an interest for not only the rock and popular music of 60s and 70s Iran, but also of nearby Turkey, India, and the Arab world.

While Pomegranates represented one of the first major compilation of ‘nuggets’ from the Middle East, it certainly wasn’t the last of its kind. Shortly afterwards, scores of compilations of obscure tracks from Iran, Turkey, and the Arab world began to abound in record stores, while fans of these genres uploaded individual tracks and homemade playlists on YouTube and other music-based social media sites. As I fell prey to the allure of these all-but-forgotten (in many cases, at least) gems from a bygone era and began creating an archive of what I believed to be the more noteworthy numbers, I began to ponder the phenomenon of the growing interest in this sort of music, particularly in the West. As well, as my collection expanded, I also started noticing considerable differences in the styles, variations, and forms of the 60s and 70s contemporary music of the countries across the Middle East and North Africa, as well as their place within the broader sphere of the respective music scenes and the zeitgeists of the region.

As one makes their way through the myriad Iranian compilations, what soon becomes apparent is that disco and funk, first and foremost, have the last word. In the swanky clubs of Tehran and the backstreets of Pahlavi Avenue (now Vali-ye Asr), as well as on television (e.g. on the popular Rangarang variety show), disco fever, with the standard dose of thumping bass lines, lush string arrangements, and primal rhythms had infected a generation of Iranians in an era often regarded as one of decadence, hedonism, and nonchalance. Accordingly, although the selection of songs on these compilations reflects everything but a ‘best of’ list, what they tend to do particularly well is capture the ambience and spirit of pre-Revolution Tehran in giving voices to artists both obscure and revered, as opposed to taking the ‘easy’ route of solely presenting the giants of Persian pop such as Googoosh, Ebi, Dariush, Sattar, Shahram Shabpareh, and so on. Were it not for albums such as these, who would have discovered (or remembered) scores of funky nuggets by the likes of Hassan Shamaizadeh, Abbas Mehrpouya, Soli, and Zia?

Disco and funk being the most prevalent styles on these albums, though, one shouldn’t disregard other recent compilations (e.g. Persian Underground, Raks Raks Raks) which have lent an ear to the Iranian rock music of the 60s and early 70s, mostly featuring obscure tracks by artists who either fizzled out as quickly as they appeared, or who later went on to form other groups or pursue solo careers (Shahram Shabpareh being a prime example of the latter). However, as was the case with most styles of rock in Iran, the sounds emanating from Tehran were largely Western in form and style; aside from their lyrics, these songs were essentially (for the most part) either Iranian renditions of Western-style rock and pop songs, or covers of numbers from the heyday of the British Invasion (think Stones, Beatles, and the like). That being said, there are a number of interesting one-offs of Persian-flavoured rock numbers from rather unlikely singers, who at rare moments in their careers pandered to the tastes of a generation with an appetite for all things Western. Watching a middle-aged Parva lip-synch her painfully groovy Mo’sem-e Gol (Season of Flowers) against clips of waterfalls and floral vistas (decades after the song’s release) perhaps exemplifies these sorts of delightful anomalies to the fullest.

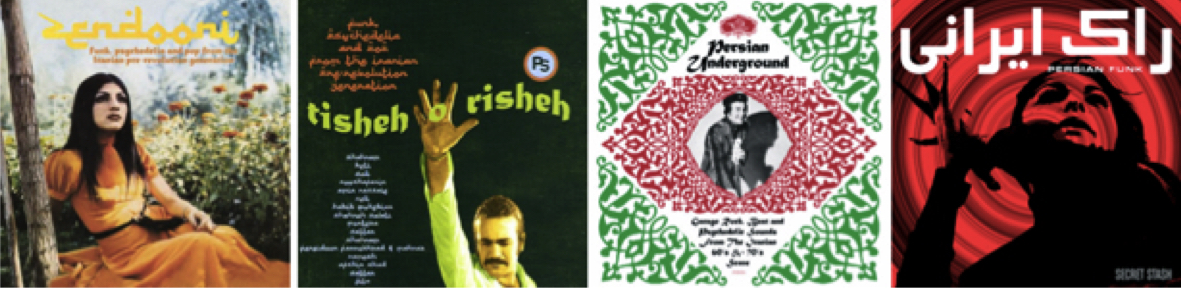

Recent Iranian 60s & 70s compilations - L-R: Zendooni (Light in the Attic), Tisheh o Risheh (Light in the Attic), Persian Underground (Persianna), and Persian Funk (Secret Stash)

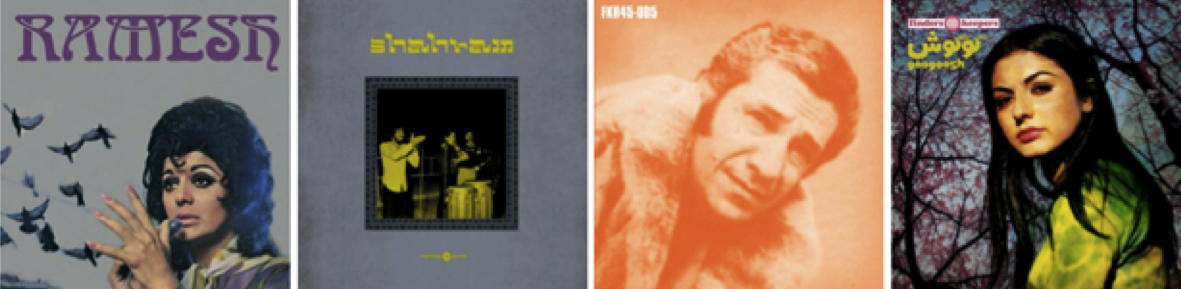

Recent Iranian artist collections – L-R: Ramesh (Light in the Attic), Shahram (Light in the Attic), Abbas Mehrpouya (Finders Keepers), and Googoosh (Finders Keepers)

The recent 60s and 70s Iranian compilations aside, the case is somewhat different when it comes to the Turkish ones. Though the odd disco or funk number can definitely be found on these albums (by artists such as Nese and Gülden Karaböcek, for instance), the majority of numbers tend to fall into the ‘categories’ of rock (particularly the hard and progressive brands), folk, and psychedelic (or psych-fuzz, according to some). In Iran, with the rare exception of musicians such as the largely obscure Kambiz, as well as singer/author Shusha (though she lived and worked outside the country), progressive rock was a terrain seldom explored and appreciated, as were other forms of rock music. Perhaps owing to Turkey’s geography (i.e. its proximity to Europe) and its exchanges with Germany, progressive rock (and rock in general) found a welcome home by the shores of the Bosphorus; and, perhaps one can say that unlike the Iranian blends of rock music, the Turkish varieties - generally speaking - managed to retain an identity that was distinctly indigenous. On the songs of Edip Akbayram, Ersen, Selda Bağcan, Cem Karaca, and of course, the beylerbey of Turkish rock music, Bariş Manço, what stands out in particular is the use of Anatolian folk instruments (e.g. the bağlama, the düdük, and the kemençe), Turkish and Caucasian melodies, and folk lyrics. Likewise, on the hard rock, psych, and folk songs of the era, this strong Turkish element and flavour is also prevalent, taking the numbers beyond the simple adaptation and translation of Western music for Eastern audiences. Amidst the fuzzed-out guitars, clashing cymbals, and booming basses can often be heard the sounds of Transcaucasia, the stories of beys, mountains, and steppes, invocations of the mystics and bards of Anatolia, and occasional tinges of Alevi folk culture.

The ‘celebration’ of rock, funk, disco, folk, and psychedelic music from the era is anything but subtle: the freakier, the funkier, the more far-out (and foreign sounding), and the fuzzier, the better, is what seems to be the agenda here

The recent fascination with popular Iranian and Turkish music from the 60s and 70s isn’t only limited to compilations, however; in addition to these, American labels such as Sublime Frequencies, Finders Keepers, and the aforementioned Light in the Attic have also recently released reissues of albums by prominent and cult musicians from the era in their entirety, as well as remixes and best-of collections. While a best-of album by Turkish rocker Erkin Koray is available from Sublime Frequencies (as are compilations of Algerian ‘proto-pysch’ tracks, Omar Khorshid reissues from Egypt, and Iraqi folk and pop albums from the 60s and 70s), Light in the Attic has released anthologies of tracks by Iranian pop stars Ramesh, Shahram Shabpareh, Abbas Mehrpouya and Kourosh Yaghmaei, as well as reissues of albums by Turkish musicians Alpay and Selda Bağcan and a collection of singles by Fikret Kızılok. As if this weren’t enough, one can also purchase a collection of Googoosh rarities, as well as Ersen and Mustafa Özkent reissues (not to mention a trippy remix of obscure Turkish numbers courtesy Andy Votel) from Finders Keepers records. With so many compilations and reissues available on the market, finding where to begin can be daunting, to say the least.

Listening to these weird and wacky songs from the 60s and 70s, I can’t help but wonder what exactly draws me towards them, and that has accounted for the recent deluge of compilations and reissues, as well as the surge in their interest, particularly among Western audiences. Many of the songs on both the Iranian and Turkish compilations are one-offs, rarities, and in certain cases, plain tripe that had hitherto remained hidden from the light of day, before collectors and DJs began to unearth them again. Aside from the odd Googoosh or Shahram Shabpareh number here and there, for instance, many Iranians would cringe with displeasure upon hearing the songs in such collections, and would hardly consider them mementos of Iran’s ‘golden’ era, or even tokens of sweet nostalgia. Indeed, yours truly has been laughed at many a time, labeled a javad (a modern slang term for a generally tacky and vulgar individual in Iran), and shown genuine concern for his sanity upon having played such songs for his friends, colleagues, and relatives, both Iranian and Turkish; for songs such as Ümit Tokcan’s Üryan Geldim, Abbas Mehrpouya’s Ghabileh-ye Leyli, and Şakir Öner’s Deli Deli aren’t exactly what one would call hits that should have been, let alone classics.

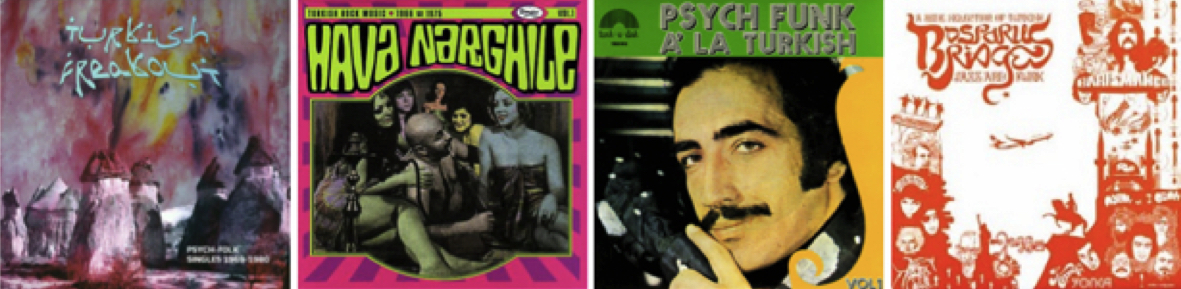

Recent Turkish 60s & 70s compilations – L-R: Turkish Freakout (Bouzouki Joe), Hava Narghile (Dionysus), Psych Funk a la Turkish Vol. 1 (Turk-A-Disc), and Bosporus Bridges (TWIMO)

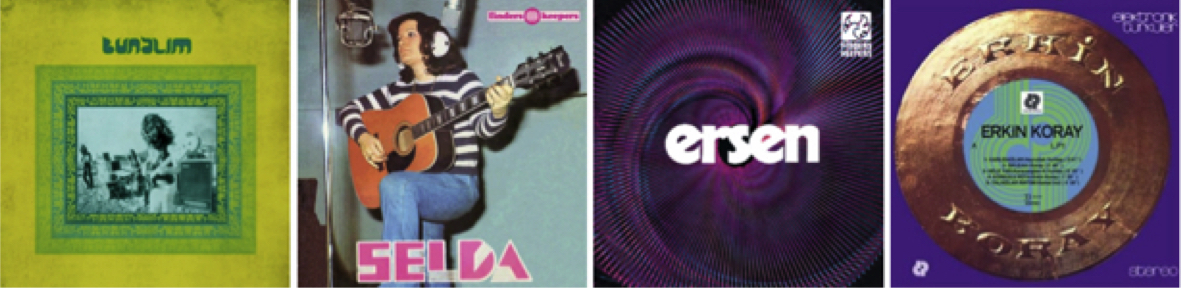

Recent Turkish reissues - L-R: Bunalim (Light in the Attic), Selda (Finders Keepers), Ersen (Finders Keepers), and Erkin Koray’s Elektronik Turkuler (Light in the Attic)

On one hand, considering the individuals behind the record labels issuing such albums, as well as the fact that they are largely being marketed towards North American and European audiences, one is tempted to attribute the rise in the popularity of such records to a sort of exoticisation and fetishisation of Iranian and Turkish music. By and large, the patrons and admirers of such esoteric musical genres are of neither Iranian nor Turkish origin, which is perhaps why songs that, as previously mentioned, might appear vulgar to many Iranians and Turks have conversely become causes for fascination and wonderment. Browsing through blogs and fan sites dedicated to such albums of Iranian, Turkish, and Arabic music, the preponderance of sleeves adorned with belly dancers, water pipes, and the proverbial description Oriental grooves can be unsettling as they are gaudy; and, as one soon learns with respect to such albums, the Western ‘celebration’ of rock, funk, disco, folk, and psychedelic music from the era is anything but subtle: the freakier, the funkier, the more far-out (and foreign-sounding), and the fuzzier, the better, is what seems to be the agenda here, for better or for worse.

As much as the deluge of these sorts of records may represent a fascination with an exotic ‘other’, though – no matter how vulgar or trite this other may be at times – I’m certainly not complaining; yes, most of the music may not be particularly ‘high-brow’, and some of the records in question do occasionally hit awful lows in terms of tastelessness; but then again, without such records, many would not have recourse to vestiges of such rare and seminal moments in Iranian and Turkish music history. On that note, part of my attraction towards [some] of these nuggets is their very rarity and obscurity, both in the West, as well as in their countries of origin. The mere notion that I and a limited audience have ‘discovered’ these occulted gems confers a sense of ownership over them, as if they can somehow be stashed away again somewhere, someplace, whether in the recesses of one’s memory, or in the prized corners of their record collection. Furthermore, listening to these songs – the Iranian ones in particular – also evokes within me a feeling of bittersweet nostalgia and yearning for an era I’ve never experienced, nor that I have any memories of. As they warble forth from my speakers – snaps, crackles, pops, and all – the resplendent plane trees of Pahlavi Avenue, the hazy peaks of Damavand in the distance, and the sweaty hordes of ‘bling’ed-out bearded men in bellbottom trousers suddenly seem as tangible and palpable as ever.

Yes, one might conclude, taking the aforementioned into consideration, the Western fascination with the music of 60s and 70s Iran and Turkey might be largely attributable to an obsession with an exotic other (in contrast with my longing for the gems of a bygone era); yes, many of the songs presented on these albums might have been better left unearthed, and yes, such albums are far from being classic compilations or representative of a ‘golden age’ of Iranian and Turkish music. Truth be told, when it comes to such collections, there’s quite a bit of digging to be done for the good stuff; but, as one will sure enough discover, those rare funky, fuzzed-out, and plain badass moments all but wiped out from the sonic records of history more often than not compensate for the effort. Seek, and ye shall find …