Reflections on the collective memories of Iran’s post-Revolution generation

Every individual carries with themselves memories, which give shape and foundation to their identity, behaviour, and perspective; but what happens when memories and experiences are recognised not only by one person, but also by many? When instead of an individual, a group of people with a collective consciousness recall and recount the same memories they all have in common? And, during the process of recollection, what other phenomena occur, and - perhaps most importantly - why and how does such widespread collective recollection come about?

Not long after the 1979 Revolution and the demise of the Pahlavi regime and the Iranian monarchy, Iran was at the peak of post-Revolution chaos, immersed in an eight year-long war with Iraq (1980 – 1988). The new government set a very different tone for, and adopted a new strategy with respect to its internal and external policies, during a time when a new generation was growing up in a society that was learning to adopt itself to its surroundings. As a result of a bloody war, and the establishment of a new Islamic Republic, the lifestyle many Iranians were used to was radically altered.

In the meantime, the expansion of the population became a part of the national agenda, with rewards being given to families based on the assumption that more children would eventually translate to more soldiers in the future. As a result, a baby boom occurred, which occurred in tandem with sanctions imposed by the West, which wreaked havoc on the lives of ordinary Iranians and the economy. Everyday life was loaded with surprises, to say the least.

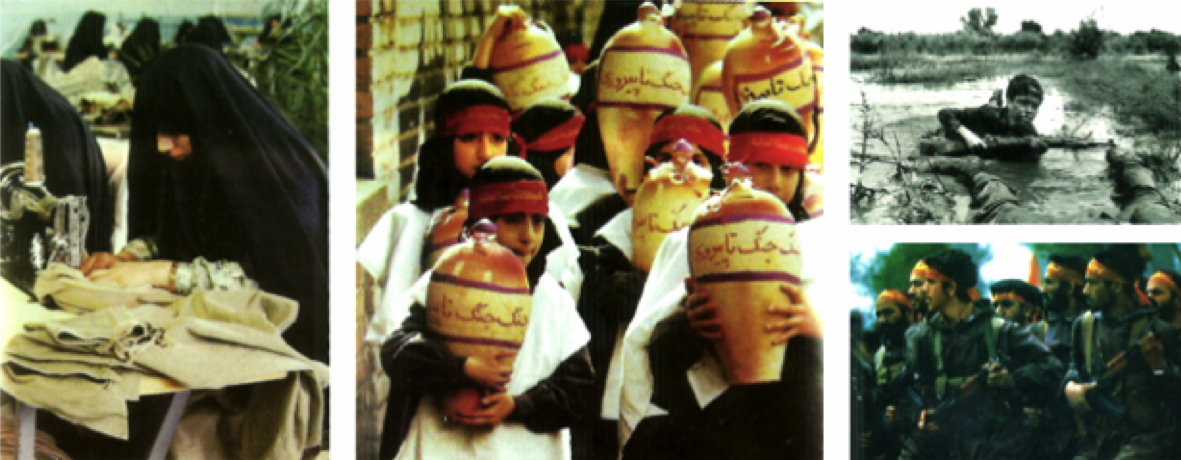

L-R: A woman producing clothes for soldiers; children carrying donations for the war effort; a popular poster of a young soldier; and soldiers during the War

The new generation of children went to school to join what was popularly termed by the government the ‘trench of science of knowledge’, a phrase repeatedly used to signify for children a holy duty in acknowledging the importance of education in the fight against the enemy. However, the nascent Islamic educational system was not without its flaws; after the Revolution, the system went through massive waves of change and experimentation. Religious elements slowly morphed into courses in their own right within schools’ agendas, Koranic studies and prayers became obligatory, and in many cases, how students were evaluated depended on their adherence to religious standards of behaviour. The European model in place prior to the Revolution was modified and stripped down of remaining Western ‘influences’, with a model of religious socialism later taking its place.

While a more traditional, masculine, and fundamentalist atmosphere began to emerge in the public sphere, another form of life was thriving beneath the surface

The contents of children’s schoolbooks also began to change on a yearly basis; every day, something or somebody was selected as a new ‘target’, whether it was the Shah and the Pahlavi regime, or other ‘oppressors’. Television channels, radio stations, and journals were all highly monitored and scrutinised, and were all aimed towards promoting the war effort as well as governmental ambitions. However, while a more traditional, masculine, and fundamentalist atmosphere began to emerge in the public sphere, another form of life was thriving beneath the surface. Not everyone was a fan of the new prescribed lifestyles, and as a result, unwritten ‘codes’ emerged in society, which would soon become part of a common, shared experience. During these tumultuous times, a ‘unified’ standard of living came into play, as did many elements that came together in a new form of popular culture. Due to the population boom during the period, this new form of pop culture had such a significant impact that its influence can still be witnessed today.

L-R: Girls in a classroom during the 80s; teachers during the 80s; an ad supporting widespread literacy; and a stamp printed during the War

The end of the war in 1988 and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini a year later signalled the end of an era. Fast forward some 20-odd years or so, and again, Iran was witnessing yet another crisis with the rise of the Green Movement and the dispute of the presidential elections in 2009. It was then that I began to recognise a great deal of visible collective longing for, and nostalgic recollections of the shared memories of the 80s and early 90s among individuals of my generation, which incited me to study the meaning of nostalgia itself. ‘Nostalgia is something of a bad word, an affectionate insult at best’, once said the scholar Svetlana Boym. Likewise, Woody Allen had little good to say about it. ‘Nostalgia is denial, denial of the painful present’ he remarked in Midnight in Paris, bringing to mind the atmosphere of the 2009 elections. It was these two remarks that made me suspect that there might be a relationship between the memories, hopes, and common wishes of my generation that could be worth exploring.

Ultimately, I came to believe that my generation was, and is going through a process of ‘conscious longing’, as I call it. In order to answer some questions I had facing this conviction, I made two Internet questionnaires, in which I asked people of my generation how they viewed the nostalgic elements and ideas from the 80s and early 90s. I focused on lifestyles, websites revolving around nostalgia from the era, social media discussions, modern reproductions of mementos from the 80s, and everything else that was related in some way or another to a nostalgic longing for the 80s and early 90s in Iran (e.g. stationery, children’s television programmes, etc.). The answers I received were very much in line with my predictions.

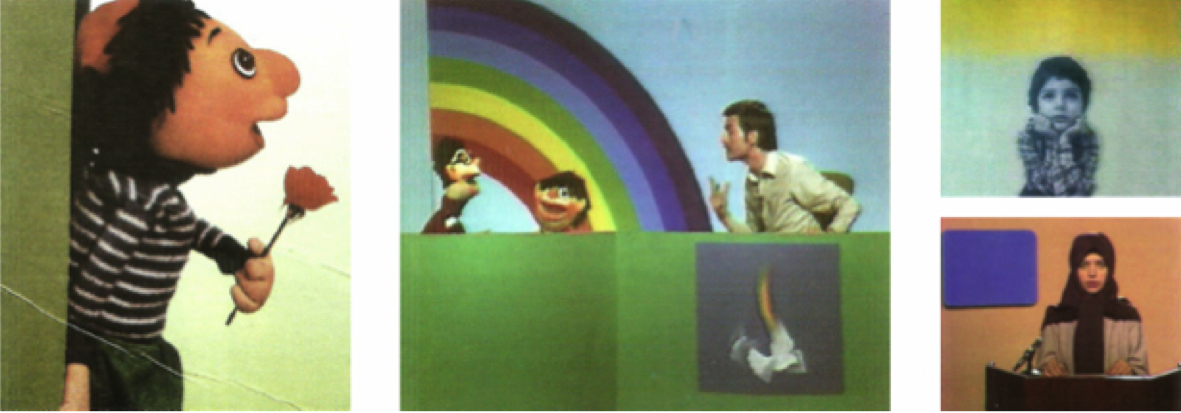

L-R: Kolah Ghermezi (Red Hat); Asemoon va Rismoon featuring Iraj Tahmasb; Ali Kuchulu (Little Ali); and Elaheh Rezaee, children’s television programme hostess

This new pop culture, however, does not necessarily deal with happy memories, but rather unhappy outcomes, and a joyful reminder of moments from a collective memory

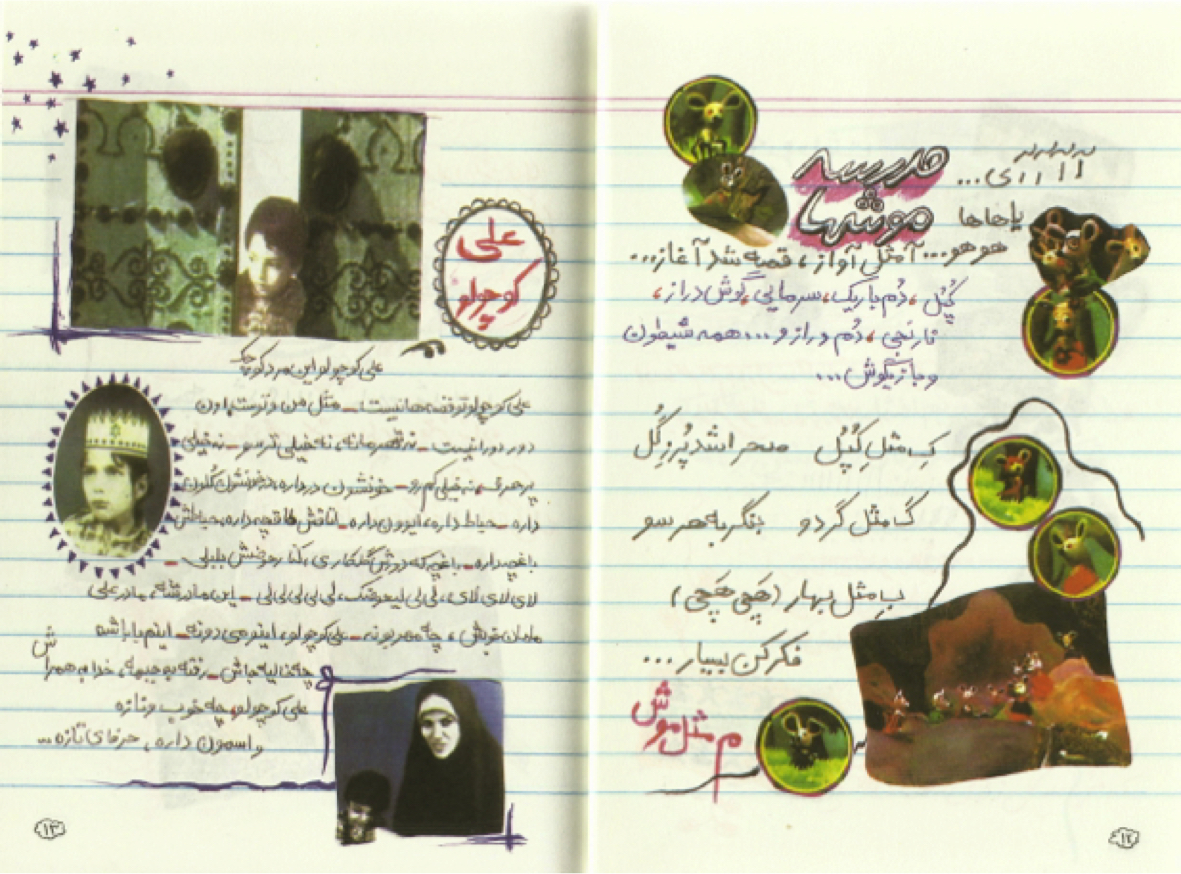

Children’s television programmes from the era are still strongly visible in the collective memory of those of my generation. For instance, many characters and images from the programmes of the 80s have been reproduced in the forms of tangible mementos, and dozens of sites and online archives exist that sell cartoons broadcasted by Iranian state television during the 80s and early 90s. Facebook pages revolving around these shows also abound. In fact, the nostalgia for that era is so strong that Iranian state television recently broadcasted special programmes (later during the evening) such as Yesterday’s Kids, which featured the same programmes from the 80s as well as their [much older] original hosts.

L-R: First grade Persian schoolbook; ‘Egg’ shampoo produced by Daroogar; Adams Khersi (Bear Gum); notebook; and a Pelikan pencil and pen eraser

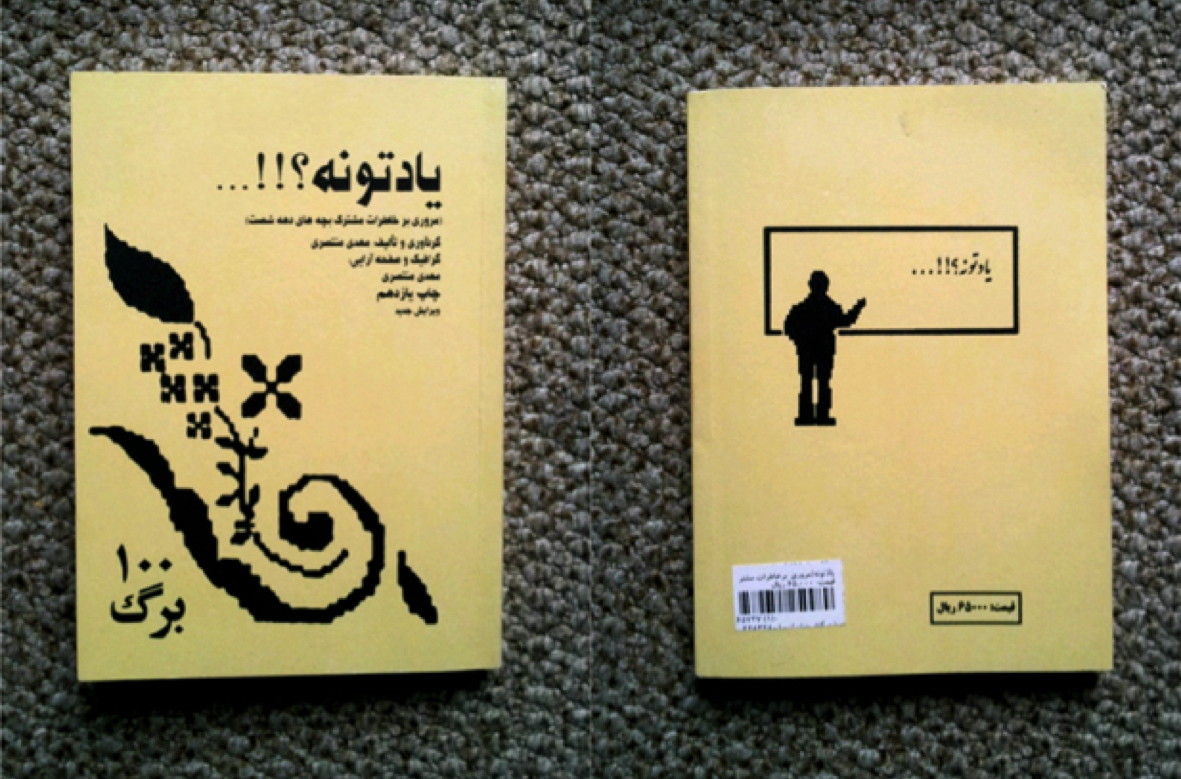

The mass production and distribution of goods – especially stationery items from the 80s – have also played a particularly strong role in this collective longing. Though the stationery products produced were few in variety, they were widely distributed and accessible, and thus became instantly recognisable symbols and icons of that era. One example is a certain notebook, mass-produced in the 80s, which was in reality the only one available in the market; and, to add to its singularity, the design on the cover was always the same: a flower motif from a Persian carpet.

While researching the history of these notebooks, I was surprised to find out about a very popular book published recently with the same cover design and aesthetics, filled with stories about the era in question. The book, entitled Do You Remember!??, was designed and written by Mehdi Montaseri, and had sold around 215,000 copies when I interviewed him last April. How does Mehdi view the success of the book, and could he ever imagine it would sell so many copies?

… By the time I found out that there were already such activities going on in the virtual world and on television, I realised that there was a ‘wave’, which had risen a few year before; and, when I released my book, the wave had turned into a mighty storm, which led to this enthusiastic demand for the book.

It is possible that the confrontation of my generation with this ‘reminder’ somewhat represents a new sort of pop culture in itself; perhaps one that has risen from the ashes of an older one, a collective and selective one. The coming about of this new pop culture has been an unconscious, collective process with conscious ‘goals’. A ‘storm’ such as this, to my understanding, is something quite powerful, since it has been able to form itself within the mould of a newer pop culture, or at least stimulate demand and production. This new pop culture, however, does not necessarily deal with happy memories, but rather unhappy outcomes, and a joyful reminder of moments from a collective memory.

‘Nostalgia is to memory as kitsch is to art’, noted Boym in her book, The Future of Nostalgia, quoting her colleague Charles Maier. With respect to nostalgia in the case of my generation, one could say that nostalgia is actually kitsch itself, as this nostalgia has found a place for itself within the realm of a new pop culture. While the artistic quality of reproduced materials such as Montaseri’s book may not be particularly noteworthy, the interaction between this pop culture and the art associated with it is still incredibly interesting. As beautiful and creative as this interaction with nostalgia may seem, though, it cannot be denied that the tragic experience of war and the exhausting post-revolutionary process have cast a shadow over the hearts of the children of my generation. Such is our collective experience that we shall always remember.

This article is a shortened, modified version of a thesis written by Pendar in the spring of 2013 in The Hague. The thesis was written under the mentorship of Doreen Mende as a research project for the Master of Fine Art in Artistic Research programme at the Dutch Art Institute / ArtEZ MFA. Click here for a selection of the questionnaires used for Pendar’s thesis, here for a visual ‘timeline’ of images curated by the magazine Herfeh: Honarmand, and here for images of an installation based on the subject of Pendar’s thesis.