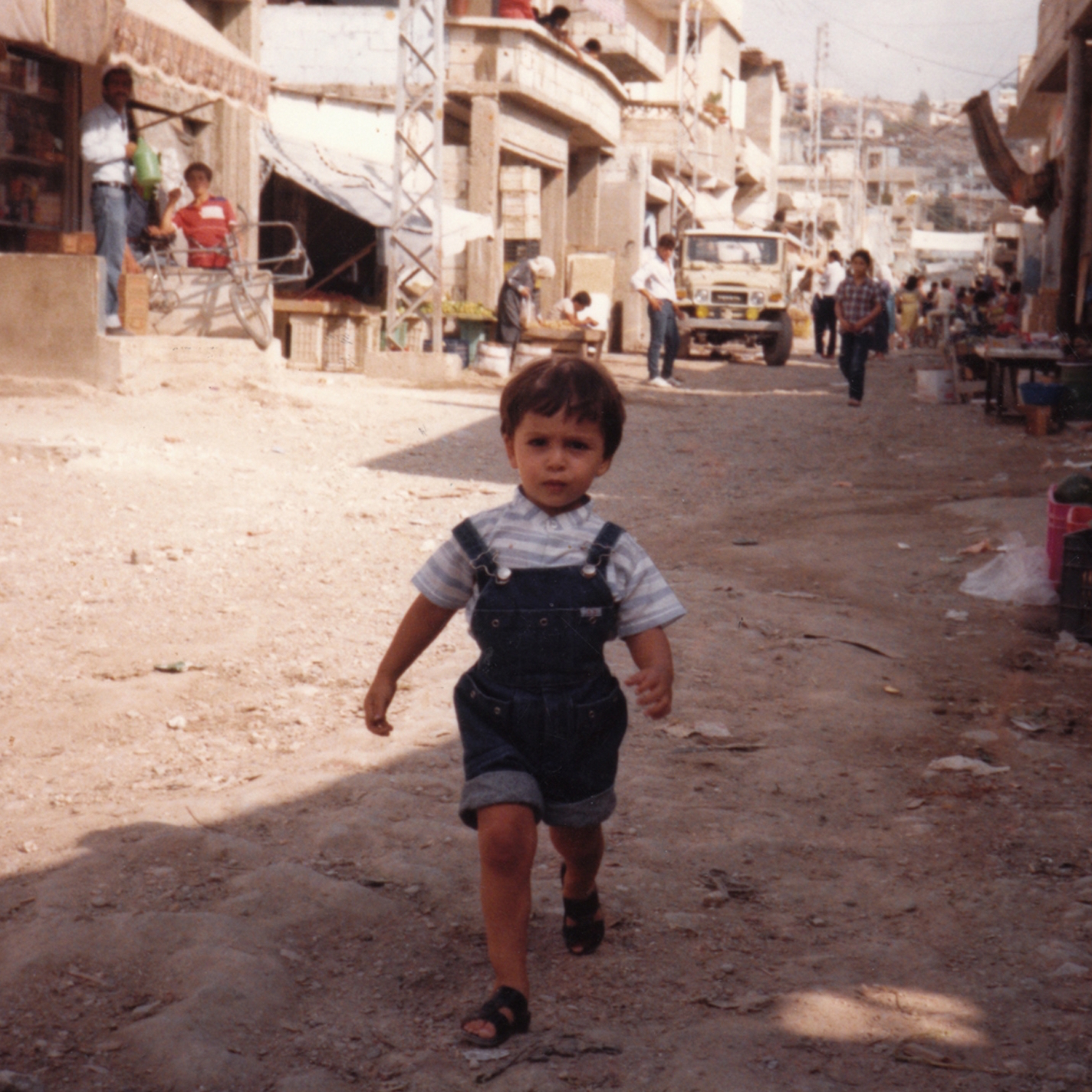

Mahdi Fleifel’s portrayal of everyday life in Lebanon’s Ein El-Hilweh refugee camp

Although Palestinian filmmaking is booming at the moment, most films tend to deal with life in Palestine itself, or in the diaspora; it’s rare that one gets a contemporary look at life for the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living in the various refugee camps across Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. Mahdi Fleifel’s A World Not Ours presents a significant and challenging response to the status quo. Shot in the Ein el-Hilweh camp in South Lebanon, Fleifel’s film presents a portrait – often grim, sometimes funny, and occasionally beautiful – of the generations of Palestinians who have grown up in this compressed and congested environment.

On one hand, Fleifel’s film features some rather disturbing spectacles. A boy casually refers to a man murdered ‘by having his guts ripped out’, and whose body was dumped by the edge of the camp. A young woman, beautifully made-up, yet stiff and terrified, leaves her family and home for a new husband in Germany. Men and children coolly wave guns, hold them cocked to their heads, or pose with them to be photographed. Conversely, however, we also see the lush curls of smoke rising from a cigarette, and the silver wings of homing pigeons flashing across the sky – recurrent symbols of space and freedom above the intensity and tension of the camp.

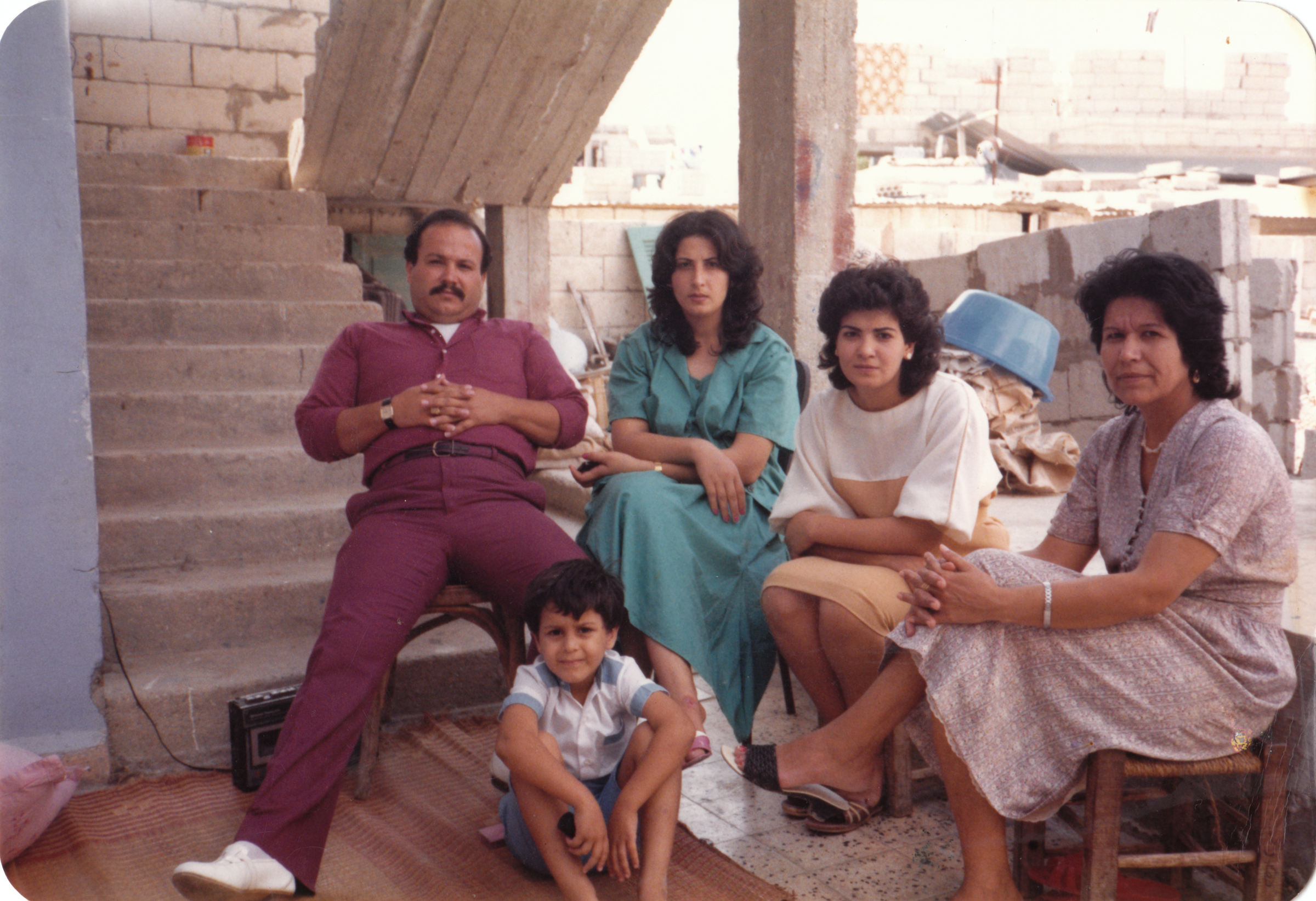

Fleifel himself grew up for a period in Ein el-Hilweh, as well as in Dubai and Denmark. He spent many childhood holidays there, and the film makes extensive use of family footage taken by his father, and later by Fleifel as a boy. Indeed, the film revolves around his friends and relatives, characters whom we get to know and feel for, and whose tales illustrate the various trajectories of Palestinian refugee life. First, there’s Fleifel’s grandfather, a cantankerous old man, who repeatedly chases away the young boys whose shouts and games disturb him, to humorous effect. Now in his 80s, Fleifel’s grandfather came to the camp from Saffuriyeh, his native village in the Galilee, at the age of 16. At one point, the director talks poignantly of the way in which his grandmother wished to visit her children and grandchildren in Europe, and how his grandfather always refused to accompany her. Having been driven from one home, he seems unable to uproot himself from the second, even for a short trip.

Sharing the same house is ‘Uncle’ Said, Fleifel’s grandfather’s much younger half-brother, who is in a state of constant conflict with him. Obsessed with his homing pigeons, and strangely isolated, it is only later on in the film that we find out that he and his brother, Jamal, were once the heroes of Saffuriyeh. As young boys barely in their teens, they fought against the Israeli army, and by the age of 13, Jamal had become a local legend on account of the traps he would set for Israeli soldiers in the camp’s narrow alleyways. However, Jamal, as we later learn, was shot in the throat by an Israeli sniper, and after more than a year of suffering in a hospital, died at only 23 years of age. Said, only a year younger and devoted to his brother, has never been the same since, having turned into an unpredictable and often aggressive ‘village idiot’ (to quote Fleifel), tolerated but mocked by men who would have once looked up to him.

Bassem – or ‘Abu Iyad’, as he is so called – is Fleifel’s best friend, nicknamed after the Fatah military commander assassinated by Israeli commandos in Tunis in 1991. Abu Iyad comes from the same generation as Fleifel; that is, of young men who grew up in the wake of the ‘glory days’ of the Palestinian resistance. The difference between the two, of course, is that Fleifel speaks several languages, and has lived abroad and become and international filmmaker in London, where he now resides. When we meet Abu Iyad, we learn that he has never left Lebanon, and rarely even sets foot outside the Ein el-Hilweh camp. As a local Fatah officer and member of the camp’s security forces, he seems to spend most of his time either patrolling the streets or sitting in the local Fatah office smoking and watching television. However, while his character may seem somewhat bland at first glance, Abu Iyad is in fact the most striking and ‘difficult’ character in the film, presenting a full-on challenge to anyone romanticising or idealising Palestinian refugees. Like thousands of other young men like him, he has little to live for: he can’t afford to marry, his days are largely aimless, and he is profoundly disillusioned. He doesn’t, however, blame Israel for this; for him, Israel is now a distant, abstract enemy that evokes few real feelings. His resounding fury, rather, is reserved for two ‘enemies’, namely the Lebanese authorities – who often deny Palestinians the chance to work in almost any profession, and who arrested and tortured him when he was 14 – and the Palestinian leadership, who after the Oslo Accords and subsequent negotiations with Israel, effectively abandoned the refugees to their fate.

For Abu Iyad, Palestine is no longer a land to be reclaimed, or a cause to be fought for; rather, it is a promise that has been broken – something he risked his life for, and which has in return utterly betrayed him

Abu Iyad’s opinions with respect to the Palestinian leadership are candidly expressed throughout the film. He points out, for instance, how he was told as a boy that his hero, Yasser Arafat (notably referred to as ‘Chairman’ rather than ‘President’, a term often used by his critics) ‘didn’t like the educated ones’. As a boy, Abu Iyad was encouraged to be ‘macho’ and a fighter, rather than focus on his studies. However, now that here is no fighting to be done, and Fatah has effectively capitulated to Israel and America, where does that leave him? Uneducated, poor, and bored, with little hope of escaping the suffocating life of the camp. ‘Fuck Palestine, fuck this “revolution”’, he says. ‘I bet most of those people who blew themselves up felt like I do. They just used Palestine as an excuse to end their lives’.

Though criticism of the Palestinian authorities and Fatah is almost de rigueur now amongst Palestinian and Palestine solidarity activists, Abu Iyad’s anger goes beyond this. He does not simply question the political stance of the West Bank, political leaderships in Gaza, or their implicit – and sometimes explicit – renunciation of the Right of Return. Unlike those from previous generations in the film – some of whom refer to Mahmoud Abbas as a ‘son-of-a-bitch’ – he appears to have rejected the whole idea of devotion to the ‘cause’ that characterises much discourse around Palestine, both internally and internationally. For Abu Iyad, Palestine is no longer a land to be reclaimed, or a cause to be fought for; rather, it is a promise that has been broken – something he risked his life for, and which has in return utterly betrayed him.

Considering the comments of those who had attended the UK premiere of A World Not Ours at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, the majority being Palestine solidarity activists and supporters amongst whom discourses about ‘resilience’, ‘dignity’, and sumud (lit. ‘resistance’) were the norm, Abu Iyad’s sentiments are particularly moving. Many of those activists responded defensively to the film’s implicit criticism of their work. What relevance, one might ask, do campaigns focused on the West Bank, efforts to stop international pop stars giving concerts in Israel, or church sales of traditional Palestinian crafts have for Abu Iyad, when he is simply trying to find a job in the dead weight of the Lebanese system? His is a voice that needs to be heard; it is the voice of a working-class generation without work, jobless and hopeless, completely disillusioned and disenfranchised. Having grown up surrounded by poverty and violence, those of Abu Iyad’s generation are a million miles away from the ‘Ramallah bubble’ of vibrant nightlife and international aid workers, and the affluent Palestinian diaspora in cities such as London and New York. What does international Palestine solidarity campaigning have to offer them?