Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige salvage a tale from Lebanon’s halcyon days

In the Arab world – Lebanon in particular – local art is largely shaped by the political instability of the landscape. Constant hostility in this part of the world not only actively influences the process of creating art and the finished product itself, but also has the potential to play a significant role in influencing and provoking cultural perceptions. A Lebanese artist may be inclined to feel a sense of satisfaction with respect to the output of contemporary art in Lebanon, in relation with the art being produced in other corners of the Arab world. However, in forming this opinion, they may also overlook the fact that Lebanon’s status as a nexus of contemporary Arab art is solely due to scattered initiatives of individuals, who are seldom able to find support for their projects among even the most liberal of Lebanese, let alone within the flux of socio-political conflict therein.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige are among the few Lebanese artists and filmmakers who seek in their practice an independent form of inquiry and research. Their projects are often reflective of an incisive investigation encompassing a range of cultural observations and historical representations within a Lebanese context. Their meticulously researched projects, as well as their experiments with various theories and interdisciplinary mediums particular to their country have pushed the borders of the practice of art as it is known in Lebanon today, opening new portals for understanding the position and culture of Lebanon, and questioning and influencing the local perception of art.

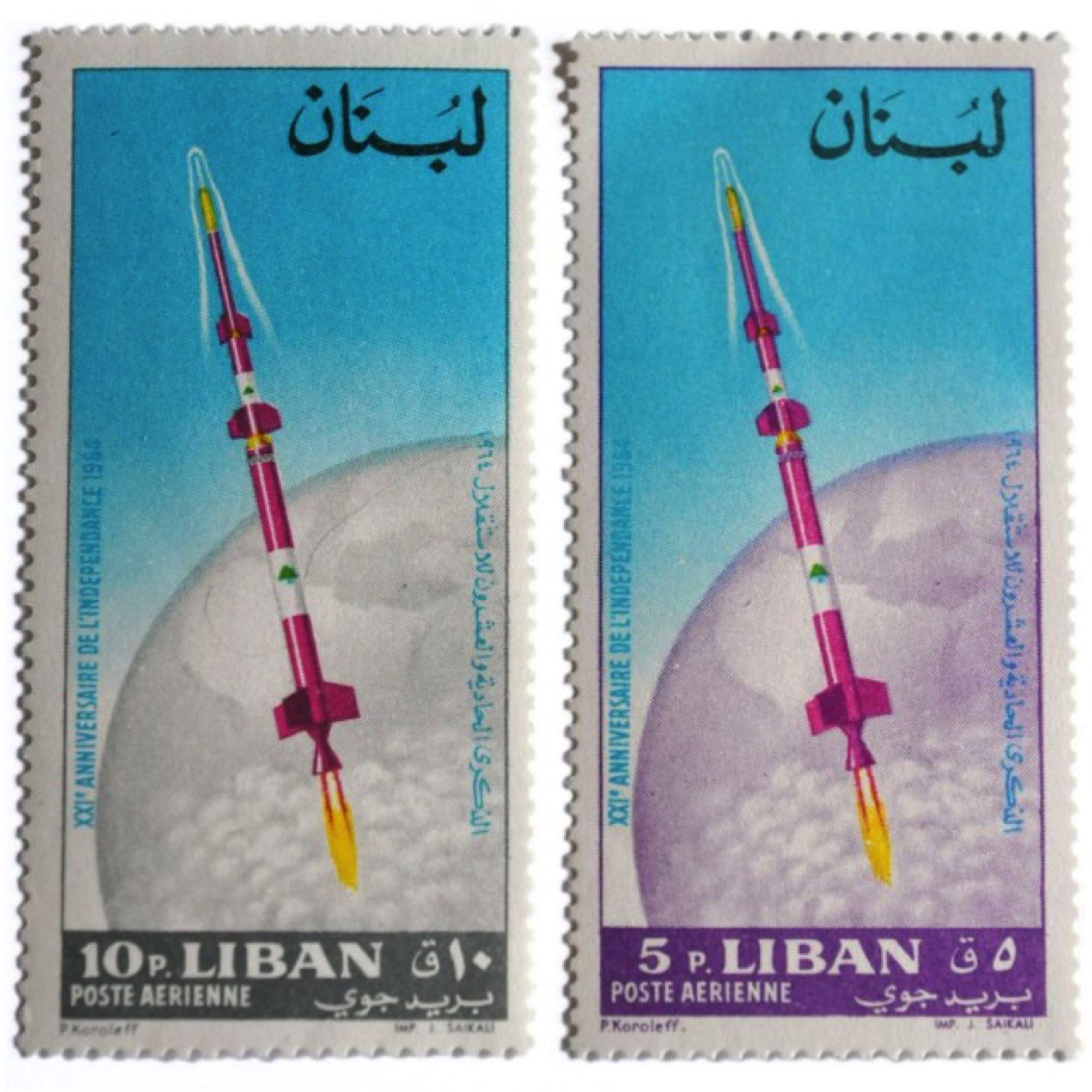

The Bird’s Eye View Festival in London, with its mandate of highlighting the works of female Arab filmmakers, recently featured Hadjithomas and Joreige’s 2012 film, Lebanese Rocket Society, a documentary tracing the history of the Lebanese space programme of the 1960s from its humble beginnings to its sudden end. As Hadjithomas and Joreige show, though Lebanon was the first country in the Middle East to produce its own rockets and initiate a space program, the story of its rocketeers is little known among the general public, and is often met with sarcasm and disbelief at best. Thus, inspired by the image of a stamp featuring a Lebanese rocket in The Vehicle - a book edited by Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari – and wanting to bring to light the forgotten story of the country’s ‘Rocket Society’, the artists set out to make a documentary in 2009.

The Lebanese Civil War left the country in a state of collective amnesia, washing away all traces of the ‘Space Race’ of the 60s from public memory. As a result, Hadjithomas and Joreige were forced to put together and artistically re-interpret hints and leftover ‘clues’ to reconstruct the story of a real, experienced memory, which had all but sunk into oblivion. Serving as an almost hallucinatory tale for the ears of the Lebanese public, Lebanese Rocket Society is not only an investigation into the history of the Lebanese space program, but also a reflection on the notions of ambition, destruction, and reconstruction. Beginning with a focus on the small team of motivated and determined Armenian students of Beirut’s Haigazian University and their ‘coach’, professor Manoug Manougian, the artists highlight the widespread support of the Rocket Society, as well as its peaceful, scientific aims. With little resources at hand, Manougian and his team created fuel from raw material, and successfully launched several rockets, each of which attained new heights as their experiments progressed. Gradually, the project expanded to include researchers from other universities in Lebanon and the surrounding region, turning into a countrywide initiative of national importance. After the launch of several larger experimental rockets – one of which almost landed in nearby Cyprus – that caused international concern, the Lebanese army also stepped in, in the hope of advancing its artillery. However, due to increasing international pressure, especially from France and Israel (according to Manougian) the dream – for whatever reasons – came to an abrupt end in the late 60s, in an era of national and regional conflicts, and during the zenith of the pan-Arab dream, spearheaded by Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Lebanese Rocket Society is not only an investigation into the history of the Lebanese space program, but also a reflection on the notions of ambition, destruction, and reconstruction

Throughout the film, Hadjithomas and Joreige map out the history of modern Lebanon from within a void of forgetfulness. After asking questions regarding the image of the proverbial rocket and what it once represented, the artists embark on a mission of spreading public awareness of the space programme of the 60s, reflecting Lebanon’s heterogeneity, energy, and political worries, both then and now. Lebanese Rocket Society is not an ordinary documentary, however. Here, the artists go beyond simply retelling the story of the Rocket Society to actively re-imagine it, as if it were never snatched from Lebanon’s collective memory and buried during the Civil War. In their approach, Hadjithomas and Joreige use art as a tool for thinking, investigating, and perhaps most importantly, positively intervening in popular Lebanese culture.

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige - Restaged (courtesy The Third Line)

Along with the documentary, Hadjithomas and Joreige have produced various artworks, each serving as a contemporary record of the past achievements of the Rocket Society. As well, in the documentary, the artists depict their reconstruction of Manougian’s original eight metre-long Cedar 4 rocket in Beirut, which they later install in the courtyard of the Haigazian University. Painted in white to symbolise the peaceful ambitions of the Rocket Society, the construction of the rocket was no easy feat, particularly in the context of contemporary Beirut, with its myriad Government organisations rife with bureaucracy. After finally receiving all the necessary paperwork and stamped approvals required to build and transport the rocket throughout Beirut, Hadjithomas and Joreige are forced to endure the arduous process yet again, when the Lebanese Government collapses in June of 2011. Nonetheless, the artists manage to pull through, deconstructing and reconstructing visual Lebanese symbols and reintroducing them publicly in the process.

Though one expects a sort of finale here, with the reconstructed rocket back in its proper place serving as a reminder of the splendour of the 60s, the artists’ work is far from complete. Rather, as the film turns into an animation, they strive to depict a possible Lebanese future, showing what the country may have looked like had the Rocket Society continued with its experiments. In the year 2025, as they show, Lebanon is a highly-advanced nation with state-of-the-art technology and facilities, sending rockets not only into the sky, but into space as well. In this futuristic world, the story of the Rocket Society is but a mere fragment of history, regarded with nostalgia. While this future is certainly admirable, one cannot help but feel saddened at what Lebanon could have become, had its ambitions not been abruptly halted. As well, it is perhaps here, more than anywhere else in the film, that parallels between the story of the Lebanese rocketeers of the 60s, and the current Iranian situation are conspicuous. Rapidly producing its own rockets, fighter jets, and tanks, in addition to landing US drones and sending monkeys into space, one can only wonder what the future holds for this Middle Eastern nation so condemned by Israel and the West, whose story so parallels that of its nearby political ally.

Far from remaining in the recesses of a forgotten past, Hadjithomas and Joreige transform the little-known story of Lebanon’s Rocket Society into a thing of fantasy and wonder, seemingly belonging to an impossible utopian ideal. Confronting public amnesia through traversing its emptiness, the artists provocatively question the ambiguity and ambivalence of the collective Lebanese memory with respect to its glorious, not-too-distant past, striving to resurrect it in a modern context. In the process, they launch their own dreamlike rockets in the Lebanese skies overhead, which have long been blanketed with political and cultural conflicts, bringing out of the darkness a lived dream which until only recently seemed like an imagined illusion.