I hear a long moan. No, it’s a song. Children’s voices intone a funeral hymn …

They won’t miss me this afternoon. I left the house when Nadia opened the door to Mrs. Khoury, the old neighbour.

‘Listen, Nadia, I’ve just heard that more roads are blocked,’ Mrs. Khoury said. ‘We may have to go without fresh vegetables and fruits again.’

‘Come in,’ said Nadia. ‘Let’s have coffee and talk. I need a break before the kids return from school.’

I usually enjoy Mrs. Khoury’s gossip. But today, I’ve decided to take a walk. I’ll be back before dinnertime. No one will even notice my absence.

Nadia has been busy all day. It is our turn to have the bridge group over this evening. She set small tables in the living room, and covered them with a green felt tablecloth. I remember the long evenings she spent cutting hearts, diamonds, clubs and spades in red and black felt. Then, she festooned them meticulously. It took her months to complete the bridge mats. She delicately arranged the patterns around the border and secured them with invisible stitches, sometimes by candlelight. Electric power failures were part of life then. Nadia once said, ‘I have become a nocturnal animal. I see in the dark like a cat.’

She placed ashtrays, pencils and notebooks on the tables. Satisfied, she set forth to the kitchen. For a couple of hours, I watched her make a Black Forest cake. She carefully sliced the cake, pursing her lips in concentration, and filled it with whipped cream and Maraschino cherries. Later, she covered the frosting with chocolate shavings, bark and mini-logs. Whipped cream is my weakness. I always get to lick the bowl.

I had forgotten the street smells. A renewed, forgotten life penetrates my senses. Jasmine hedges and tamarind mix to form a strong cocktail faintly tainted at times by the exhausts of cars. I love the emanations coming from the restaurants’ cooking. There are quite a few around here. I think I smell fried fish. Today must be Friday then, because I heard Nadia ordering sole fillets, over the phone, for tonight’s dinner. At this very moment, Nadia is probably asking Mrs. Khoury to give her recipes for new sauces.

I don’t go out often anymore. I grew out of the habit because of the uninterrupted shelling. Luckily there’s a remission now. No fighting, no bombs exploding in months. Things are calming down. I’m getting old.

I imagine the two women sitting in the kitchen. The curve of Mrs. Khoury’s back brings her face to her waist. She always thrusts her chin forward when walking as if it were an antenna. She loves to be the centre of attention. Her stories are punctuated by her chin pointing in different directions, dragging along her round head, around which two long braids are rolled like white ropes. She hushes everything in a low, raucous voice. With this war lasting for more than twelve years, she never lacks dramatic stories to tell.

I don’t go out often anymore. I grew out of the habit because of the uninterrupted shelling. Luckily there’s a remission now. No fighting, no bombs exploding in months. Things are calming down. I’m getting old. I should get some fresh air now and then. I’m almost an object in the house. When friends visit, I sit comfortably aside on a sofa by the window, and lean on a silk pillow. My eyes follow the sun’s reflections all over the room. Sometimes, I close my eyes and pretend I’m sleeping, but I remain attentive to every single word they say.

It’s fun to walk along the narrow sidewalks. There are fewer sandbags now. Everything seems peaceful. Young boys in uniforms sweep the streets and hold their post in intersections. It’s quiet at this hour. Only a few women beat the pavement with the weight of their grocery bags. A new beauty salon has opened next to L’Éclair’s bakery: Coiffure Latifa. I heard Nadia’s friends say, ‘It is always full. Incredible, considering the prices!’ I watch women coming in and out the revolving doors. People have learned to live from day to day and enjoy the present moment to its fullest. A tall lady is just coming out, smiling. maybe convinced that her new hairstyle fits her crescent-carved profile.

I continue downhill. The road slopes slightly; I’ll worry about it on my way back. I reach a vegetable stand. Vegetables and fruits gorged with sun look the same year after year. A fat woman with red swollen cheeks argues, ‘A hundred Pounds for a kilo of tomatoes! What are you trying to do? Starve us?’

‘Go grow your own,’ says the merchant, menacingly. ‘We’re risking our necks crossing the city from one end to another. It’s getting more dangerous everyday.’ His rough stained hands delicately rearrange the symmetry of the tomato heap. He wipes the ones on top with a cotton rag.

‘One hundred pounds!’ repeats the fat woman. ‘They only cost a pound before the war.’

She leaves without the tomatoes.

Mrs. Khoury’s words come to my mind. We could go through another difficult period. It wouldn’t be the first time we’d live on rations. Luckily, we’ve never lacked food so far. We’d go to our summerhouse in the mountain. There, in Reyfoun, we have a beautiful orchard: peaches, apples, pears, and plums. It is breathtaking in spring. By the front of the house, vegetables grow almost without care. Giant mountain tomatoes, parsley, onions, zucchinis … A fellow from the area looks after it in our absence.

Half the summer was spent canning. The kitchen was converted into a real lab. All operations were timed. Vegetables and fruits were blanched or pasteurised. Nadia was proud of her jars. We’d bring them all down at the end of the summer to Beirut in several trips. They were everywhere, on the shelves, over the counters, inside and on top of the cabinets.

I hear a long moan … Children’s voices intone a funeral hymn. Some kids walk in line like in a procession. They carry on their shoulders a couple of nailed planks on which graffiti read: ‘God forgive’ and ‘Rest in peace.’

It sprinkles a little. I walk faster to get under the nearby arcades. Many businesses are relocated in East Beirut now. Some people are rebuilding their store for the third time. The East side has grown to be quite self-sufficient, at least for everyday needs. Women practically never go to West Beirut, unlike men, who have to go back and forth for business. But it is much safer, now.

I cross the next set of barricades. So many things have changed everywhere; nevertheless, I know my way home. Here and there, broken pipes pop out under the opened concrete, spitting water like a spring over the asphalt. It’s surprising to see clear water coming out of the entrails of the earth.

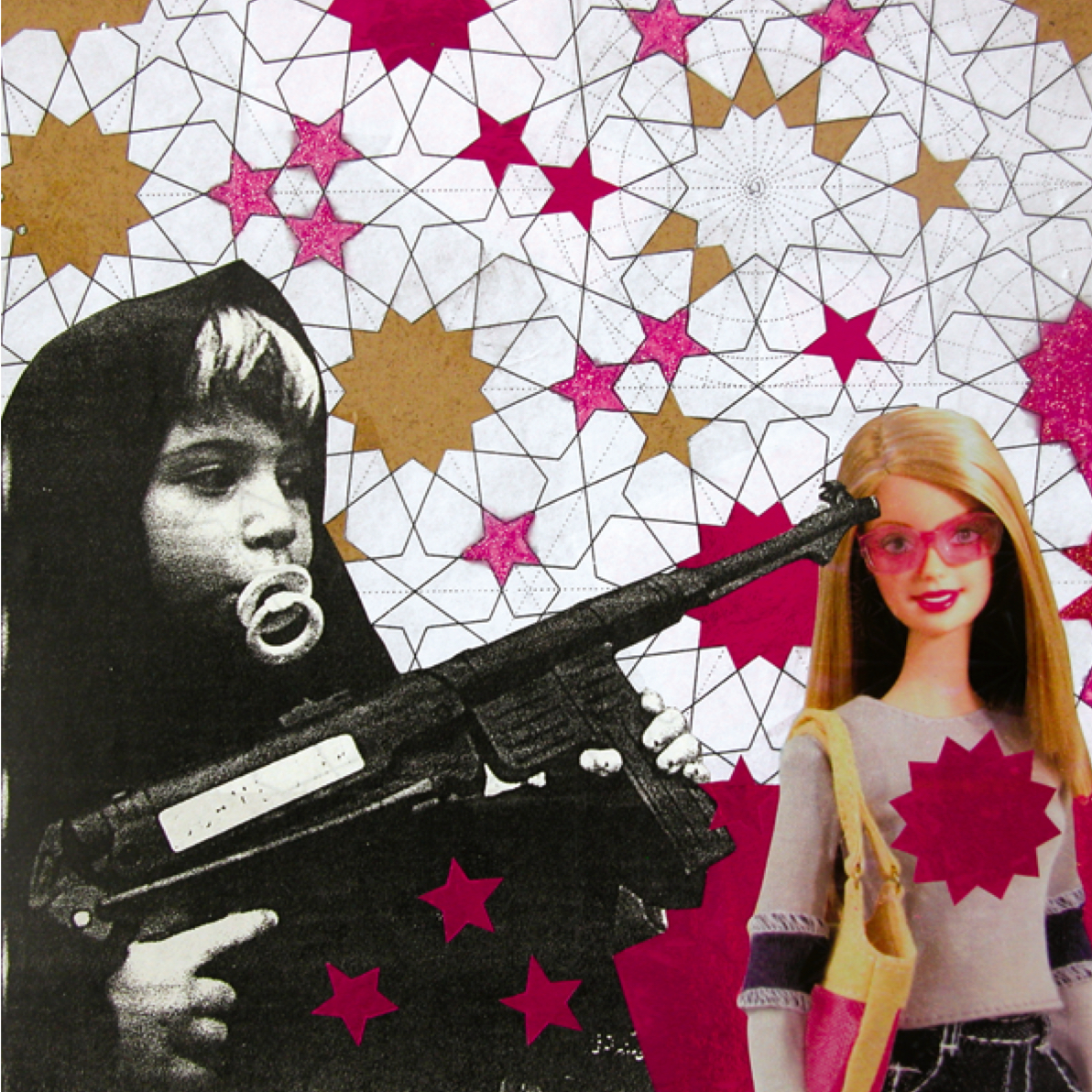

A girl washes laundry in a plastic bucket right in the middle of the sidewalk. She throws the gray sudsy water on the side, and rinses and wrings strongly. I’ve heard of refugees from Tyre and Sidon who take shelter in empty houses. They come with their bundles, sometimes a goat or a pair of chickens. I hear a long moan. No, it’s a song. Children’s voices intone a funeral hymn. Some kids walk in line like in a procession. They carry on their shoulders a couple of nailed planks on which graffiti read: ‘God forgive’ and ‘Rest in peace.’ I must have walked a long time. I’m tired and dread the long way back. The kids stare at me with empty eyes. They’ve just noticed me. They put their planks aside and approach me carefully, pointing their long sticks like machine guns.

‘Call Mohsen,’ orders the oldest, ‘Go!’

Nadia’s friends used to smile at me, ‘Your cat’s fur is as shiny and soft as black mink. It’s very well taken care of.’ Her husband once complained, ‘You’re crazy! If anyone knew you fed that cat chicken livers when people are starving …’

‘I couldn’t get near those people if I wanted to,’ she replied. ‘I have no way of helping them. You know it. Besides, the cat only eats leftovers. It doesn’t cost us anything.’

‘Look! He is a real big one!’ The boys are getting really excited. I can tell they aren’t after my fur.

‘Mohsen! Over there, shoot, shoot, hurry! Don’t let him get away!’

From Flying Carpets.