Khaled Akil: storyteller. Revealer of truths. Armed to the teeth.

Khaled Akil is a Syrian photographer residing in Aleppo. After a brief sojourn in Istanbul, he and his wife returned back to their country to play their part in what could perhaps be called Syria’s most trying moment in decades. Caught in the midst of a bloody civil war, Khaled nonetheless found the time to talk to us about his art, and about the Syrian situation.

You’re originally a lawyer, by profession. When did you begin taking photographs, and how did you end up going down the artistic route?

I have two idols in my life – my father, and my grandfather. My maternal grandfather is a judge by profession, and has always had an obsession with photography, as far as I can remember. I spent my childhood with him, taking photos with his cameras, and later, for my 16th birthday, he gave me my first camera as a present. It was at that point that my passion for photography began.

As for my father – he is one of the most famous painter in Syria, from whom I learned that the most important thing in one’s life is to do what they love doing. This is the route that I have taken in life, and which I continue to take. After completing my studies in Law and Political Science, I discovered that I couldn’t live without making art that would ‘serve’ my country in the best possible way.

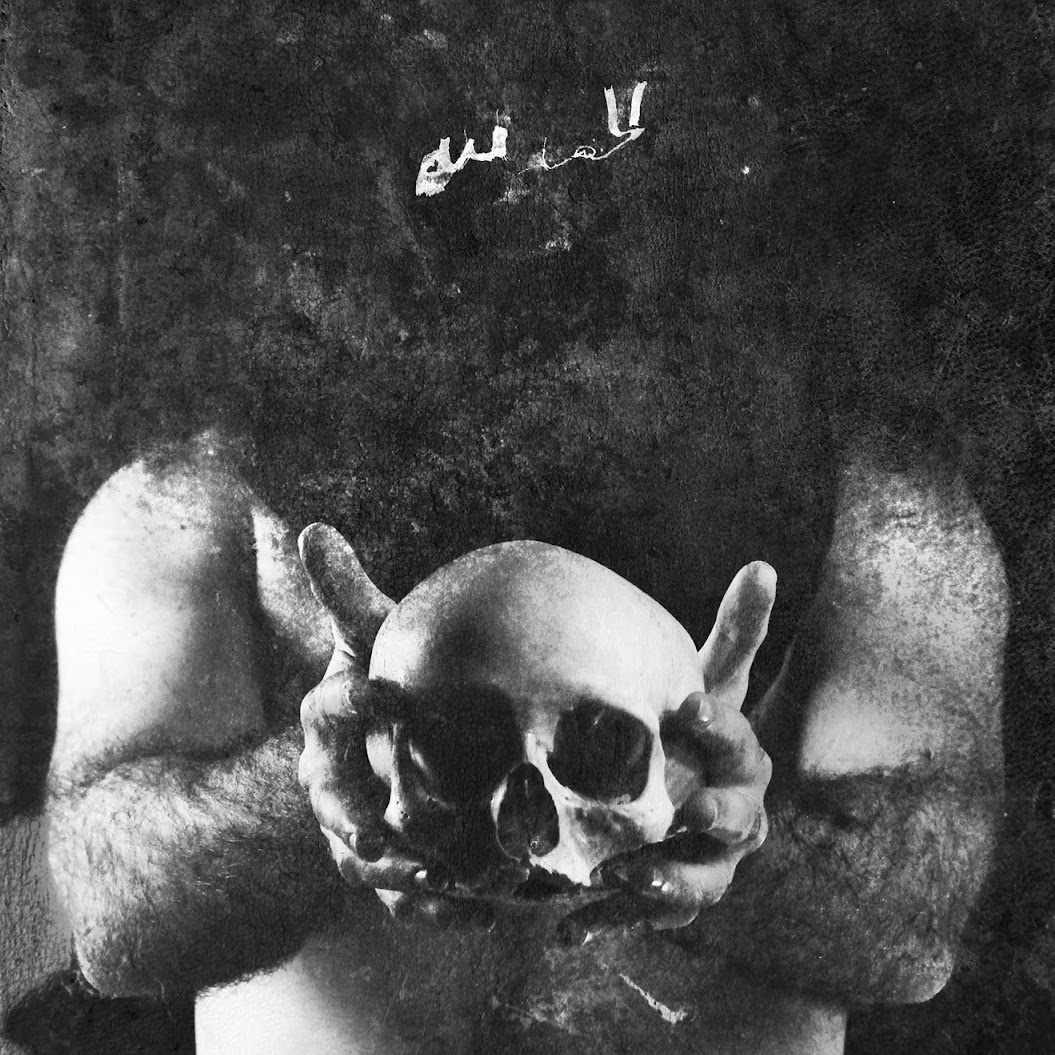

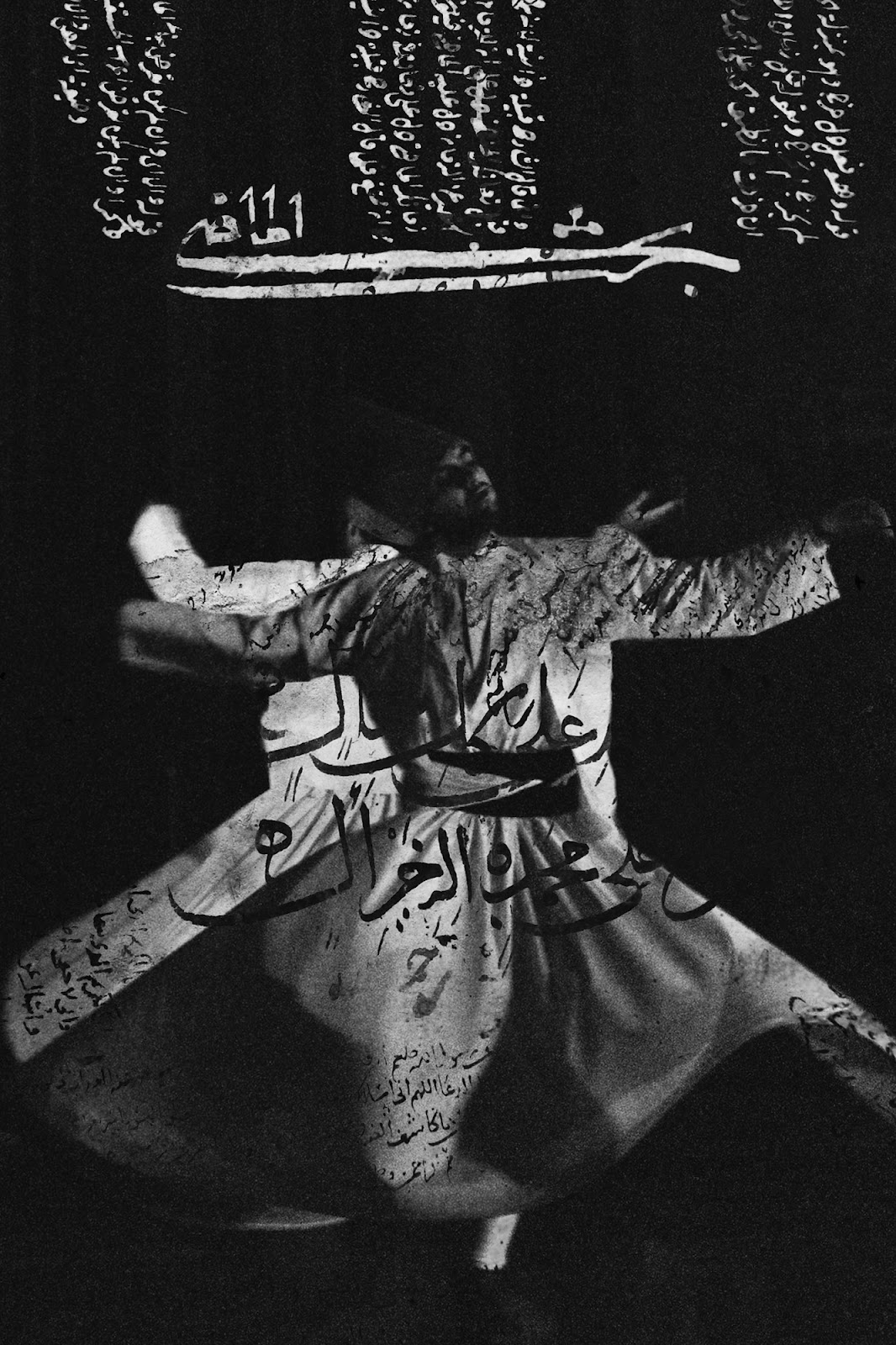

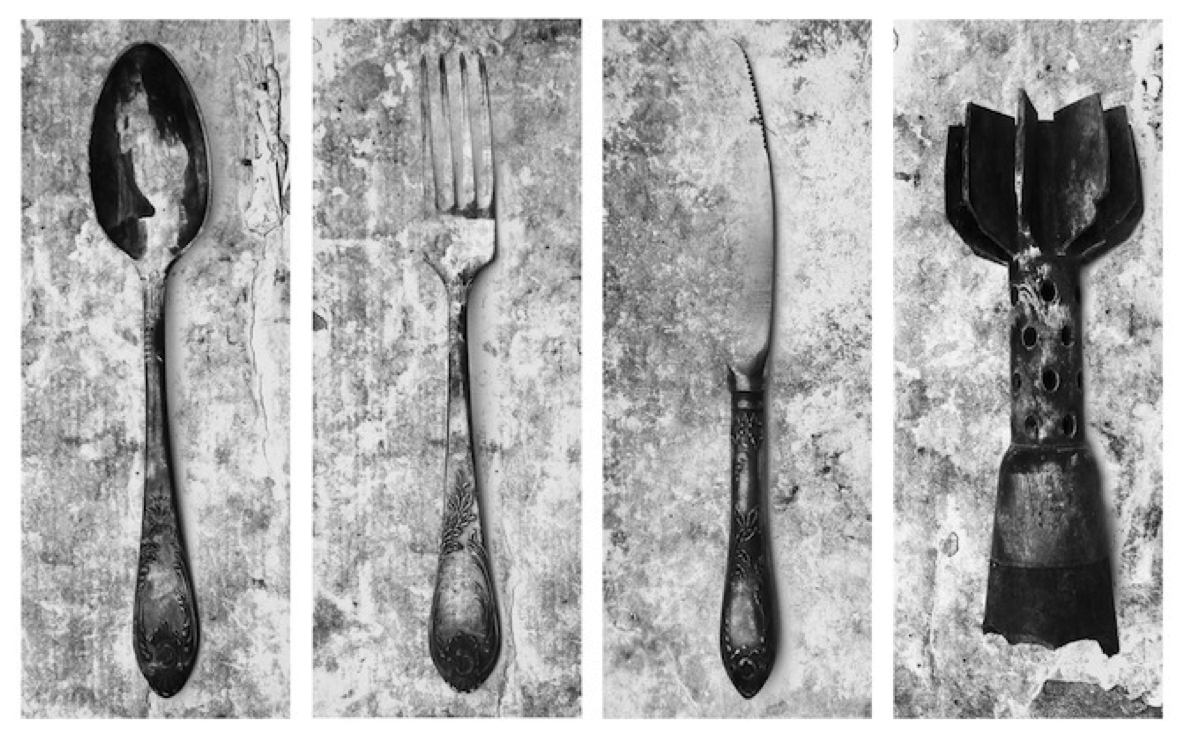

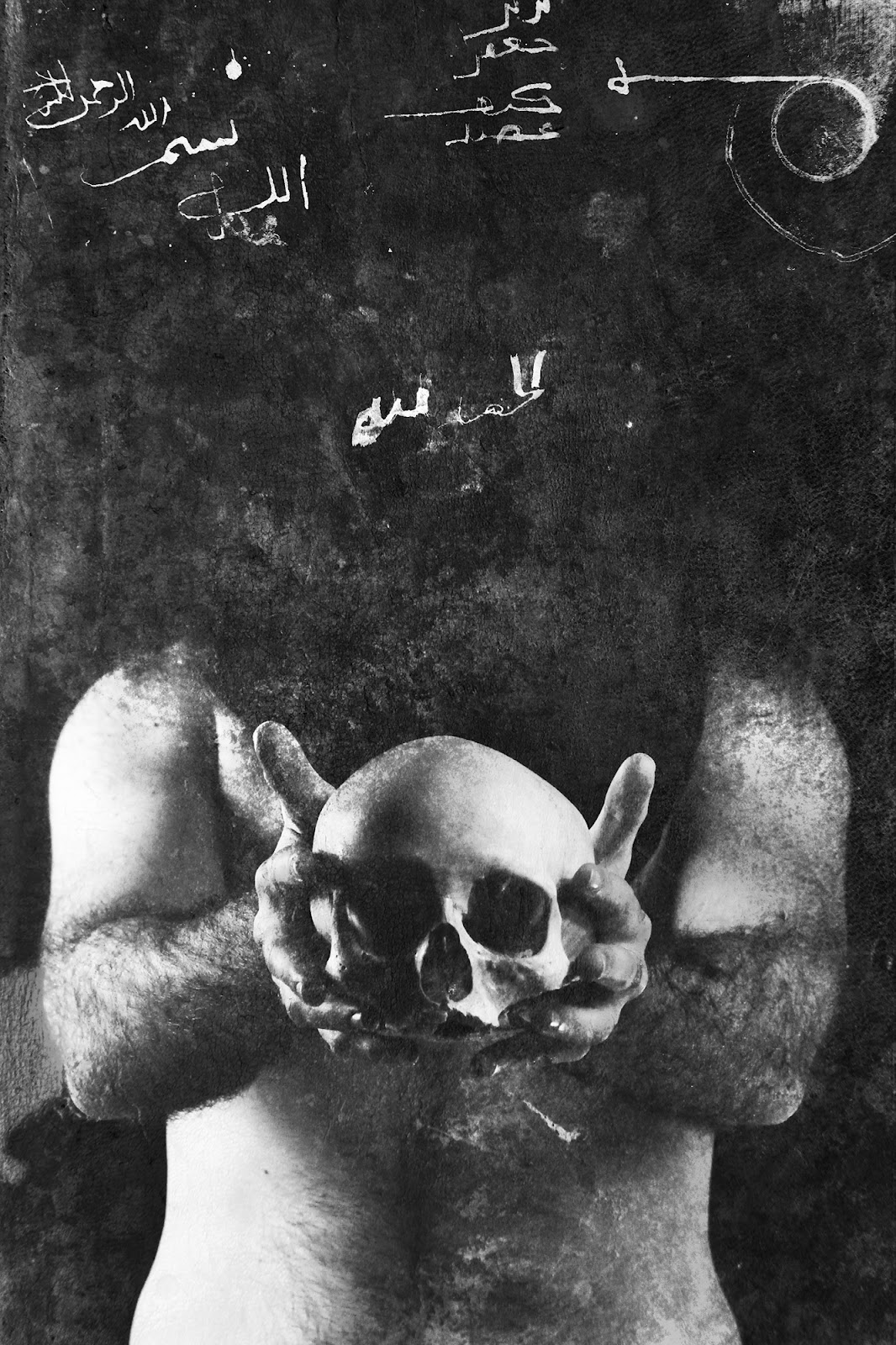

What is the story behind the photographs in the Unmentioned series? You seem to be tackling a variety of different subjects in the photographs, such as religion, war, and sexuality.

The story behind the photographs in the Unmentioned series is the story of my life, the story of Syria, and simply put, the story of all the countries in the Middle East.

Three things are behind the war, and the complicated times we live in now in Syria: religion, sex, and politics.

The Unmentioned is a blatant ‘NO’ to the war in Syria, and the dictatorship in the region. I began working on the pieces two years ago, way before the revolution began in Syria, as I felt that the way were living would eventually result in the Syrian revolution. That is why I tried to raise some awareness among Syrians, by focusing on the real problems they should be aware of, so that the revolution wouldn’t take on a religious aspect, and more specifically, an extremist one.

When I first started working on the pieces in the series, people here in Syria took me for a fool for exposing ‘negligible taboos’. Now they understand what I was trying to say, but it’s too late, unfortunately.

Have the photographs in the series ever been exhibited in Syria? If so, what has been the response to them thus far?

Yes – the 25 works in the Unmentioned series have been exhibited in Aleppo. People were shocked, and others criticised the ‘way of pointing directly to our taboos’, as they put it.

Three things are behind the war, and the complicated times we live in now in Syria: religion, sex, and politics

To be sincere, I am the first artist in Aleppo who has had the courage to say ‘NO’ to the censorship implemented by the regime, as well as Syrian society. I’m also the first who has rejected the idea of making ‘beautiful’ art that does nothing but lie to one’s fans, and one’s audience.

The role of art is to present the truth, and sometimes this means exposing the ‘ugly’ truth, resulting in ‘ugly’ art.

For a short while, you left Aleppo for Istanbul, only to return. What made you return to Syria, amidst all the recent upheavals?

The importance of Aleppo and its geographical location near the Turkish border caused it to become the final obstacle in the revolution in Syria, or as they say, the ‘mother of all battles’.

Knowing that Aleppo was under siege was the reason my wife and I returned to Aleppo. Being an artist doesn’t really support one’s city and one’s people in itself, and when the war broke out in Aleppo, we felt we had to be there, like so many other people who were trying to rescue and help other people in need.

How has the turmoil and chaos in Syria affected your work as an artist? Are you still producing work these days?

Of course, the turmoil has affected my work. A photographer holding his camera is the same as a militant holding his Kalashnikov. The camera is a weapon, because it reveals the ugly truth, and removes all masks.

As for my new works, the recent upheavals have had a major role in expanding my perspective on war; that is, I now know that war is the same all over the world, and that it is a global language that everyone understands. My role is to translate this global language into artworks that relate to a specific country called Syria.

How is the art scene in general coping – if one can use such a word – with the situation there? Would it be wrong to assume that, as they say, ‘life goes on’?

First of all, I must affirm that art for an artist is neither a job, nor a hobby; it is a basic need, in my opinion.

As for the art scene in general, I can’t say that ‘life goes on’, as an art scene is a collective scene in which everyone participates: the artist, their fans, the audience, and the media, of course. Currently, art is a luxury, whereas documentary work is a must, and a need.

Unless your goal is to benefit from the suffering of your own people, today it would be better, perhaps, to let go of your ego a bit, and try to feel and live through the suffering yourself. This is an experience in itself that can affect everyone’s lives.

It’s often been mentioned that misfortune and suffering are excellent sources of creativity. Would you agree in the case of Syrian artists – living both in Syria, and in the diaspora?

You are definitely right – creativity is born from the heart of suffering and misfortune. As a Syrian artist living in Syria, and witnessing the horror with my own eyes and ears, my work is obviously significantly different that the art of artists living abroad.

A photographer holding his camera is the same as a militant holding his Kalashnikov. The camera is a weapon, because it reveals the ugly truth, and removes all masks

Dealing with the subject of Syria is way too problematic; I always say that you can never understand it unless you live it. On the other hand, when political awareness rises, it is generally accompanied by a social and cultural awareness. That is one of the many benefits we have enjoyed as a result of the Syrian revolution. As I’ve already mentioned, the war has played a major role in expanding my artistic perspective, which in a way is a sort of ‘blessing’ for me.

In the recent uprisings around the Arab world, art – street art in particular - has often served as a catalyst for change, and has had a major influence on the public psyche. What role, if any, is art playing in pushing for change in Syria?

To tell you the truth, street art is not something we’ve really had in Syria, as a result of 40 years of dictatorship that forbade any form of art that didn’t glorify the regime.

Art needs freedom, and it brings a limitless political and social awareness. That is why I can simply say that art is forbidden in Syria. Art in Syria is not ‘powerful’ enough to bring about change in the best possible way.

People in Syria are still afraid. In fact, they are also – believe it or not – afraid of freedom. We need another 40 years just to clarify that you don’t need guns and Kalashnikovs to make change; you need a beautiful mind and an ethical culture to bring about the most peaceful change imaginable.

What does the near future hold in store for Khaled Akil – artistically and personally?

I truly hope that the near future will be better than the present. On the bright side, The Unmentioned will potentially be exhibited in Istanbul in December 2012, as well as elsewhere, most likely in Europe.

My new works are being produced with sadness and anger, more than anything else, and will reveal the truth of the past 17 months, which have seen over 30,000 dead in a devastated ‘free’ country.

In fact, as I am talking to you, all I can hear around me is the sound of bombardments, gun shots, and ambulances – this says it all!

As for my personal near future, all I can say is that my wife – whom I married only five months ago – and I are trying to start a new life; a peaceful and truthful one, despite all we’ve lived through, and are about to live through.